‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī (1)

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Dear listeners, welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

In today’s episode recorded in Paris, Mr. Frédéric Lagrange will be talking to us about Sī ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī.

Now people will think that ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī visited Paris!

He never did, did he?

He did visit Vienna though, according to Qasṭandī Rizq.

The most important details about the life of the major musician in the 19th century are non-confirmable miscellaneous information learned through his contemporaries and through his friends, such as poet Khalīl Muṭrān.

The major source on ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī is Qasṭandī Rizq’s book “Al-mūsīqa al-sharqiyya wa-al-ghinā’ al-‘arabī” that relates the most important information about Al-Ḥāmūlī’s life. Fortunately, this book is full of precise details on the life of ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī, but we will see that they are, unfortunately, mostly doubtful because they are illogical.

True. So the details on Sī ‘Abduh’s life are not precise.

Also, it seems that Qasṭandī Rizq was extremely partial to the royal family governing Egypt before the revolution of 1952, as he presents Khedive Ismā‘īl as well as ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī and his biography as if ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī were actually one of the pious worshippers of Allāh.

‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī was born between 1836 and 1845 not far from Ṭanṭā, probably in a village under the jurisdiction of Ṭanṭā, to a father who was a coffee trader. It seems that his older brother had a disagreement with their father and that both teenage brothers fled their home and reached Ṭanṭā were they were given shelter by muṭrib and qānūnist Prof. Sha‘bān. The latter saw promising signs in the voice of ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī and exploited him to a point where he forced him to marry his daughter in order to guarantee that he stays with her and most importantly, that he would not go to Sha‘bān’s major competitor Prof. Muḥammad al-Muqaddim.

But ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī will go to Muḥammad al-Muqaddim.

Indeed.

By the way, a muḥaddith in Ṭanṭā told me that the problems between ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī and his brother with their father were actually caused by their father’s wife, which is of course a traditional problem in Egypt.

Exactly.

Al-Ḥāmūlī ended up divorcing his first wife and joined Al-Muqaddim in Ṭanṭā.

Then he moved to Cairo where he sang, in the beginning, the traditional repertoire of muwashshaḥ. According to Qasṭandī Rizq, it was the pre-dawr period. He sang these muwashshaḥ following the style of Shākir al-Ḥalabī who had brought these Aleppan –or more generally Levantine– muwashshaḥ to Egypt in the late 17th century.

By the way, there is a mix-up concerning the latter’s name: Qasṭandī Rizq calls him Shākir al-Ḥalabī while Muḥammad Shahāb al-Dīn calls him Shākir al-Dimashqī.

Also, I think that there were dawr already: Al-Maslūb was already there, among others… I think that there were also dawr, not only muwashshaḥ. What do you think?

I think that during his period, the dawr was not intrinsically different from the ṭaqṭūqa, the dawr’s structure was still not clearly or completely independent from the ṭaqṭūqa’s. There is a clear and significant freedom to improvise in the dawr, even in the first dawr such as Al-Maslūb’s or others’ dawr.

‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī, then still a young boy wearing the traditional jilbāb (gallabiyya) in the Alexandrian style and the dark coloured ṭarbūsh, complained about Al-Muqaddim who ill-treated him and exploited him exactly like Sha‘bān before him. So he left him and formed a takht that soon became the most important takht in Egypt. This may have happened during Sa‘īd Bāshā’s era, but we lack this kind of precise information.

‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī is described as am innovator and was thus incriminated by traditionalists. Of course, I have no idea what Rizq means by the term “traditionalists”. It may imply musicians such as Al-Shalshalamūnī, Al-Muqaddim, or Qasṭandī Minassā among other major musicians in the 19th century. Qasṭandī Rizq as well as other sources describe ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī as an innovator because he broke the fixed rules of singing. This, added to his powerful and pleasant voice, helped his reputation reach the aristocratic milieu, to such an extent that ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī was admitted into Khedive Ismā‘īl’s court in Qaṣr al-‘Ābidīn (Al-‘Ābidīn Palace).

Sources claim that in the beginning of this phase, he was forbidden to sing in public or private weddings without the written authorization of the Khedive himself. To ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī, such conditions were degrading, so they were revoked and he became Ismā‘īl Bāshā’s favourite muṭrib, and an Afandī or a bourgeois if I may say.

He removed the turban.

Actually, he never wore a turban. He used to wear the mountains’ ṭarbūsh that he replaced with the very elegant and classy Istanbul ṭarbūsh.

And he replaced the “gallabiyya” with a suit.

Exactly.

These sources also state that ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī used to sing while seated.

Actually, we must find out when Arab muṭrib started singing while standing up, when this habit replaced singing while seated…

Could it be born from the singing theatre where songs were performed while acting, and thus while standing up? And it later became a habit…?

It is possible. It could also be because the voice can reach farther if the performer is standing up instead of being seated. What do you think?

Munshid in mosques as well as in ṣūfī ceremonies chant while being seated, still their voices are very strong.

Well…

I do not know if this is the reason…

Maybe they remained seated because they used to hold an instrument: muṭrib for example used to hold a ‘ūd and had to remain seated. So, when they stopped holding the ‘ūd, they were able to stand up and sing.

Maybe they wanted to copy western performers… one of these western influences ones does not notice. People think that western influence is limited to the “major”, the “minor”, or the musical instruments used in the takht or orchestra or Arabic band. Yet, there is a western influence that is not that obvious and may be more influential, effective, and changing as to musical practices. Some western influences may be much deeper and more important than the obvious ones such as the instruments…etc.

Are you talking about the habit of singing while standing up?

Yes, added to how music is used, to the music industry…etc.

Even sound production.

Of course.

So he became an Afandī and Ismā‘īl Bāshā’s favourite muṭrib. He sang while seated, his hands covered with expensive rings, holding an amber sibḥa (beads) in his right hand, rubbing pieces of ambergris on his hands, and smelling them while singing. Isn’t this still practiced today?

True. It happens a lot. I have personally seen many munshid rubbing lotions or oil/grease on their hand, or pouring some on a handkerchief they would bring close to their nose now and then to clear it from dust. Others who sing while playing the ‘ūd pour oil on their right sleeve or on the outer part of their pick –the eagle feathers on the pick– so the oil would enter their nose while they move the pick on the ‘ūd, and thus clear it from dust.

Since ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī was also a ‘ūdist, this may have been his own “version” during concerts.

Did Umm Kulthūm put something in her handkerchief?

Mostly yes… Umm Kulthūm’s father was a chanter and she was a high-standard muṭriba… She certainly did that since her breath was even throughout the whole concert.

Sure.

Now back to ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī… He’s the one who was chosen to sing at great events, such as the wedding of Khedive Ismā‘īl’s daughters, and especially the major wedding ceremonies offered to the people of Cairo and all of Egypt: “Faraḥ al-anjāl”. Anjāl refers to the sons of Khedive Ismā‘īl: Tawfīq, Ḥusayn and Ḥasan. These ceremonies took place in 1873. It is said that huge canopies were installed going from Al-‘Ābidīn Palace to the Nile. Those who know Cairo geographically may doubt this story. Personally, I can’t imagine canopies going from Al-‘Ābidīn Palace to the Nile.

One may believe canopies were installed in every street going from Al-‘Ābidīn Palace to the Nile, but certainly not spread from here to there.

Exactly.

Al-Ḥāmūlī sang during the great evening of the anjāl’s wedding, and is said to have sung dawr “Allāh yṣūn dawlat ḥusnak” beautifully.

Knowing that, amongst the 19th century and early 20th century muṭrib, ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī was the most influenced (I won’t say that he imitated him) by the voice of ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī, let us listen to him singing the dawr.

(♩)

‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī was a member of Sī ‘Abduh’s biṭāna, wasn’t he?

‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī was a member of ‘Abduh’s biṭāna. And it is said that, for a specific event, even Al-Manyalāwī sang in ‘Abduh’s biṭāna. He was not a member of ‘Abduh’s biṭāna, he just joined it for a specific event.

To perform radd after Sī ‘Abduh.

Exactly.

By the way, Qasṭandī Rizq’s book states that ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī used the ḥijāz kār for a dawr for the first time in the performance of “Allāh yṣūn dawlat ḥusnak”. It is said that he learned this maqām from Istanbul, which is hard to believe: first because the ḥijāz kār maqām in Egypt only consists in placing a ḥijāz jins onto a ḥijāz jins, a very ordinary operation that does not necessitate a visit to Istanbul in my opinion.

Also, placing the ‘ushshāq aspect onto the ḥijāz’ position from the maqām’s jawāb was done too. Moreover, Muḥammad Shahāb al-Dīn performed both muwashshaḥ “Isqinī al-rāḥ” and “Zāranī al-maḥbūb” to the ḥijāz kār in Egypt.

I honestly doubt that they brought maqām from Istanbul. This statement may be a result of the nationalism that appeared in the early 20th century. I doubt this actually happened because they only used maqām to which muwashshaḥ could be composed, that they performed themselves, and that were already written in the book “Safīnat al-mulk”. While the melodies they brought back from Turkey followed the Turkish pattern. In fact, I think the tradition is common to Egypt, the Levant, and Turkey. There is no big difference.

You must clarify your point stating that this reflected the nationalistic influence in the history of Egyptian music, which intrinsically implies the existence of this influence or the mutual influence between Turkish music, Levantine music, and Egyptian music. Where is the nationalism in this? Or is it that this nationalism lies in the fact that the Egyptians took this Turkish maqām and adapted it to the Egyptian taste?

Exactly. I meant that he adapted it to the Egyptian taste… And then a musician would come and save Egypt from the Turkish influences…etc. It’s the same old song…

All I know is that there might be a direct Turkish influence on the instrumental level, i.e. the bashraf and the samā‘ī, but not on the vocal level. I doubt that he went to Turkey and brought back some maqām. He may have brought back bashraf and samā‘ī, but nothing else.

God knows.

During these private concerts, ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī met Almaẓ, the queen of ‘ālima in the 19th century –we have previously discussed the subject of ‘ālima. Of course the term ‘ālima must not be understood following the image conveyed by Ḥasan al-Imām’s 1960’s movies… not at all. This appellation was given to all professional lady musicians in the 19th century, including muṭriba –muṭriba was the synonym of ‘ālima in the 19th century. Almaẓ was the most important and most famous ‘ālima in the 19th century, maybe along with Sākina.

So ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī met this legendary figure we barely know anything about in the last third of the 19th century.

Let us talk a little about Almaẓ and listen to some excerpts of songs that were not attributed to her, yet that are said to have been greatly interpreted by her. One source states that Almaẓ was born in 1819, which is not very logical. Other sources state that she was the daughter of a builder and learned singing while carrying bricks on her head, which is also hard to believe. Others that may be closer to the truth, state that she was born to a bourgeois family and that her father was Azhari Sheikh Sulaymān al-Ḥalabī –of Levantine origin–, who owned a laundry in Bāb al-Khalq district… God knows.

Of course not the same Sulaymān al-Ḥalabī who killed Kléber.

Of course not.

It is said that she was the pupil of Sākina Bēh and that she surpassed her master.

What is the story about Sākina Bēh?

I personally doubt a ‘ālima could be granted the Bēh title, whether a second or first rank Bēh. They maybe added it as a mark of respect and praise.

Of course, women could be granted the “Hānim” title at most, not the “Bēh” title…

It is said that Almaẓ sang behind a curtain and chanted some verses of the Yāsīn Surah to conclude her concerts.

I believe this. I believe that they concluded with the Quran because in their early 20th century recordings all the ‘ālima –in the traditional meaning of the word, I do not imply Munīra al-Mahdiyya– recorded the Quran.

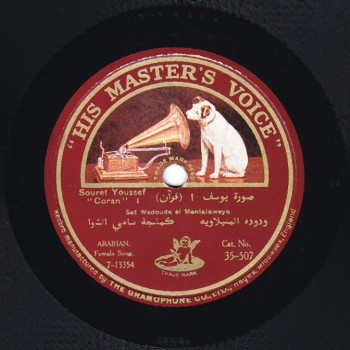

Maybe not all of them, but certainly a significant number of ‘ālima recorded the Quran at the beginning of the century, including Amīna al-‘Irāqiyya and maybe the most famous ‘ālima Wadūda al-Manyalāwiyya whose voice was marvellous and who recorded verses of the Yūsuf Surah. There is a funny anecdote concerning Wadūda al-Manyalāwiyya. The label on this record is very famous because of what is printed on it: by mistake or for commercial purposes, God knows, the label carries the following “with Sāmī al-Shawwā’s takht”. Of course, there is no violin in the recording… this is a funny yet very confusing story.

The Maryam Surah with Sāmī al-Shawwā’s takht… the Yūsuf Surah with Sāmī al-Shawwā’s takht…

Let us listen to an excerpt.

(♩)

With this marvellous tilāwa performed by Wadūda al-Manyalāwiyya, we reach the end of today’s episode.

But let us first issue a call to all lady reciters: please, start performing tilāwa again. We have had enough listening exclusively to male Quran reciters since the 1940’s or 1950’s.

We have reached the end of today’s episode

We will meet again in a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

“Min al-Tārīkh” is brought to you by Mustafa Said.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)