The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Dear listeners, welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Today, we will be talking about ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Afandī Ḥilmī.

What can you tell us about ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Afandī Ḥilmī?

Despite ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī’s reputation, his life story is as little known as that of any other muṭrib of his era.

It seems that he was born in Banī Suwayf in Egypt’s Ṣa‘īd and kept a light accent of this region all his life. It appears clearly in some of his recordings, such as in qaṣīda “A-lā fī sabīl Allāh” that ends with the verse “Wa-yunṣifunī minki” to which he adds “Yā sharikēh”…

(♩)

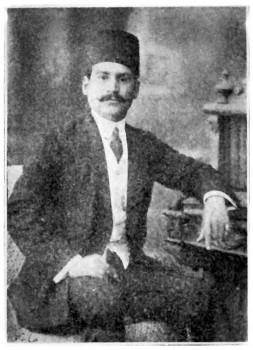

Old sources do not tell about his early years. It is only known that he learned directly from the masters of the khedivial school their principal dawr. Some sources indicate that he was born in 1880, an improbable date contradicted by the photos published by Gramophone, as well as by his large repertoire that must have required a long and direct acquaintance with the great masters… so he was probably born in the 1850’s or the 1860’s.

He worked as a young man for the rich Alexandrian notable Ismā‘īl Bāshā Ḥāfiẓ.

Not muṭrib Ismā‘īl Ḥāfiẓ ?

Of course not…

This allowed ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī to meet in the latter’s Salon the late 19th century’s great voices from whom he learned his art.

It is also said that he was a madhhabjī in the takht of the late 19th century’s most famous composer and muṭrib Sī ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī whom he liked to a point of listening to his old cylinder recording of qaṣīda “Arāka ‘aṣiyy al-dam‘ ” that he recorded many times inspired by Al-Ḥāmūlī’s performance and developing it.

Yet, concerning ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Afandī Ḥilmī’s performance of qaṣīda, I suggest we listen to another one to the same maqām bayyātī, qaṣīda muwaqqa‘a “Lam yaṭul laylī” marvellously written by Bashshār Bin Burd. “Kitāb al-Aghānī” mentions that Bashshār Bin Burd considered this ṣawt as the best and the most beautiful poetry he ever wrote.

The qaṣīda is as follows:

Lam yaṭul laylī wa-lākin lam anam Wa-nafa ‘annī al-kara ṭayfun alam*

*(“alam” does not mean pain, it means visited… Let us not forget that Bashshār Bin Burd was blind)

He continues:

Rawwiḥī ‘annī qalīlan wa-‘lamī Annanī yā ‘Abda min laḥmin wa-dam

Wa-idhā qultu la-hā jūdī la-nā Kharajat bi-al-ṣamti ‘an lā wa-na‘am*

*(she refused to answer me)

Again, the only means of communication between Bashshār Bin Burd and the beloved woman ‘Abda were the words and the voice.

Let us listen to ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Afandī Ḥilmī…

(♩)

According to the description that reached us, ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Afandī Ḥilmī was a short brunet who seems to have adopted the Afandī suit early on. He was famous for his elegance, forcing his rich sponsors such as Muḥammad al-Bābilī to pay huge amounts of money for his outfits that had to be ordered from Paris.

But these are details… Let us stick to the point, i.e. the voice of ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī.

…A sad voice

Sad and tragic… His voice was at once flexible, strong and tragic. He was especially comfortable in high ranges and soon attracted the attention of the audiences.

He was also known for his odd manners, mostly during concerts. According to some sources, he sometimes interrupted a concert for trivial reasons, decided to sing to the sea, or slept during a concert, or stretched the duration of a song, embarrassing qānūnist Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād’s takht.

The memoirs of the music milieu reported to the great collectors of 19th century recordings describe him as an addict to alcohol and hashish, and maybe opium, which helped him sustain the physical effort required by long nights and to live up to his legend.

This mix between higher art and his tendency towards “impertinence” and different types of pleasure can be deduced from the fact that he was, in his time, the only muṭrib among the great masters who sang ṭaqṭūqa that were reserved to female singers at the end of the 19th century, i.e. great muṭrib did not normally perform simple ṭaqṭūqa for their audience. ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī did, yet he dealt with ṭaqṭūqa as if they were dawr, adding creative ornamentations even if the words were “immoral”, or rather “pleasantly indecent”, such as in ṭaqṭūqa “Amara yā amara” that is actually the story of an adultery, or the story of a playful girl who attempts to outmanoeuvre those who wanted to enchain her.

Here are the lyrics:

In kunti khāyif min abūya

Abūya nāyim we-wākil tatūra

We-in kunti khāyif min ummī

Ummī ‘alayya satūra

We-in kunti khāyif min ukhtī

Ukhtī ‘āyyi’a we-mashhūra

We-in kunti khāyif min el-bawwāb

A‘ma we-rigluh maksūra

(♩)

But one must forget about the this immoral/lightly indecent text and focus on the beauty of the voice and the beauty of the performance, as well as all the creative ornaments he brought during the performance.

Strangely, he used to record during the same session, ṭaqṭūqa such as “Amara yā amara” or “Yā nakhlitēn fī el-‘alālī” and works like “Yā naḥīf al-qawām” and “Waghak mushriq bi-el-anwār”.

True! He also sang “Lam yaṭul laylī” and other qaṣīda whose lyrics came from the middle ages, the Abbasid era.

Isn’t his experience in/knowledge of both these opposite types strange?

Concerning the strangeness of his moods, it is said that he visited Bilād al-Shām, and that while roaming in the streets of Damascus, he fell in love with a beautiful face in the Jewish quarter.

He went back to Egypt where a very strange ṭaqṭūqa – not a folkloric ṭaqṭūqa, i.e. not one he took from the female repertoire and developed then presented as a work fit for a takht– was specially written for him. It is “Ḥalālī balālī” that he recorded many times, including an extraordinary version with Gramophone, as well as versions recorded by Baidaphon and Odeon. The only one who recorded it after him is his nephew Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy.

But we must listen to “Ḥalālī balālī” in the voice of ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī. Which version will you play for us, Mustafa?

Gramophone’s version… what do you think?

Great… recorded on two sides.

Yes, two sides, Gramophone’s version recorded on two sides

Beautiful.

(♩)

Yūsuf ‘Awaḍ says that ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī had not seen an ordinary woman, but a muṭriba who was famous then in Damascus, Ḥasība Mūsa.

She could have been Ḥasība Moshēh or another muṭriba among the Damascene ‘ālima… God knows.

The odd manners and the habits of the music milieu at the beginning of the 20th century may be the way of life mentioned in the memoirs of British Sound Engineer at the beginning of the 20th century describing the quantities of alcohol, cocaine, and drugs artists drank and used throughout their concerts that started early in the evening and lasted until 2 or 3 in the morning.

Couldn’t they record in the daytime?… They only recorded during the night because they did not work during the day…

They just did not want to work in the daytime.

It seems that ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Afandī Ḥilmī died in 1912 in Alexandria after a feast of sea turtle, and that his corpse was discovered by the takht members.

This is according to Sāmī al-Shawwā’s memoirs.

Exactly.

After being a regular singer who became famous because of his beautiful voice at the beginning of the century, ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī took advantage of the record companies that spread his reputation and became their spoiled child. He had barely become famous and recorded his voice on phonograph discs that many amateurs pretended insolently to imitate him. That is according to Iskandar Shalfūn.

After he had earned a place at the court of the Khedive, he was invited with violinist Sāmī al-Shawwā to Istanbul in 1910 to sing in front of Khedive ‘Abbās’ mother. He also seems to have given an extraordinary concert on a boat on the Bosphorus.

‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī was a competitor of Al-Manyalāwī who despised him according to the musicians’ milieu. Yet they sat together on the throne of singing after Al-Ḥāmūlī and ‘Uthmān passed away.

Some sources describe him as a singer, not an artist, while acknowledging the power of his voice and his unique emotions, whereas others only saw him as an imitator of Al-Ḥāmūlī.

A Syrian writer who appreciated him and described a more precise image of him said that his singing came naturally and was free of any artificiality or fabrication, and that he was not knowledgeable in maqām and melodies, and only composed his improvisations in mawwāl and light ṭaqṭūqa.

Such judgements must be explained as I think they are arbitrary and not quite correct, considering that the complexity of Khedivial singing requires precise theoretical and technical knowledge, even if it is verbal and through impregnation and rubbing shoulders with the singers. Moreover, a singer like ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī had to pass the difficult taḥzīm test (granting of the belt) to be allowed to sing in the places where he performed. Thus, unlike a performer in popular musical art, his particularity was not limited to a simple innate singing talent. He was also a learned muṭrib, but the characteristics of his performance policy may convey the impression that he was not educated because he chose not to be a “trustworthy” singer and not to abide by the composed melody. This does not mean that he was not knowledgeable as to all the specificities of composing, maqām and measures. It only means that he imposed his tragic personality onto the work. Isn’t his voice full of tragedy and misery?

His voice is full of tragedy and revolt.

Claiming that he did not know about maqām is not true: we have a recording where he asks the qānūnist to change the maqām.

The same applies to the beats: we have several recordings of muwashshaḥ “Yā naḥīf al-qawām” and muwashshaḥ “Waghak mushriq” that are to two different beats, the samā‘ī thaqīl (10) and the mukhammas (16). In one recording, he followed to the beat, while in the second one, he totally ignored it, and in the third one he did something in the middle, sometimes abiding by the rhythm and sometimes not.

Thus I think that his insubordination is deliberate, while the secret of the tragedy is not really understood. Do you have an explanation?

I think that we must compare the version where he completely ignores the rhythm to the version where he abides by it.

Let us listen to the muwashshaḥ…

Here are the Odeon and the Gramophone recordings of muwashshaḥ “Yā naḥīf al-qawām”

(♩)

Dear listeners, we have reached the end of today’s episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

We will meet again in a new episode to resume our discussion about ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Afandī Ḥilmī with Prof. Frédéric Lagrange whom we thank for being a permanent guest of AMAR.

“Min al-Tārīkh” is brought to you by Mustafa Said.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)