The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Today’s episode is about musical dialogues, a pleasant and interesting subject that we will be discussing with Mustafa Said.

I personally only know about the musical dialogues in Boulevard Theatre and Opera Bouffe plays, i.e. in the western singing art. I do not know if this art was imported into Arab music or if it originated in it.

Most of the information I read in the written press and in music theory writings states that this art stemmed from the musical theatre. Knowing that the latter is an imported form then musical dialogues are consequently an imported form too. Yet this is neither totally true nor totally wrong, since musical dialogues, in their form heard in 20th century recordings –many of which we will listen to throughout our discussion– are not necessarily born from the art of Karakoz, of udabātī, of ḥakawātī, or of the afyajiyyya, as these were either written or sung. Even in the Levant, there was shared zajal including two persons, one singing and the other one answering him. Thus, the musical dialogues recorded in the early 20th century might have been born, yet not necessarily, from traditional folklore: one can’t deny that Aḥmad Sharīf was influenced by the Karakoz traditions that also inspired Salāma Ḥigāzī and Sayyid Darwīsh. Still, the early 20th century singing theatre plays of Salāma Ḥigāzī, Sayyid Darwīsh, Zakariyyā Aḥmad, and Dāwūd Ḥusnī, added to al-Qabbānī and Mārūn al-Naqqāsh before them, took their form from the west: their art did not rely on the khayāl al-ẓill or the ḥakawātī. They applied the western form when they deemed it appropriate. Even the plays of Abū Khalīl al-Qabbānī and Salāma Ḥigāzī, or Mārūn al-Naqqāsh before them, are either a direct interpretation of the west’s tragicomedy, or an Egyptianization / Arabization of these theatre styles. So, since they did not rely on the existing forms for an Arab singing theatre, their dialogues consequently relied on this form.

Mrs. Gina al-Rihani, Najīb al-Rīḥānī’s daughter, said that her father, who was a friend of major French actor Louis Jouvet, went every year to Paris where he watched plays that he surely adapted later.

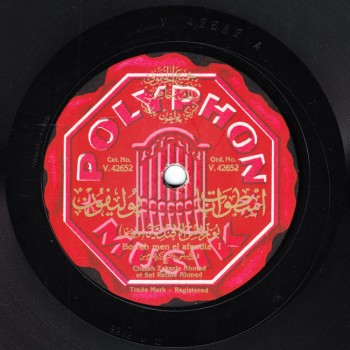

This indeed shows clearly in the recordings through which he was supposed to be promoting his plays with Badī‘a Maṣābnī, such as the tune “Burrīh min el-afandiyya” –probably composed by Dāwūd Ḥusnī– that both him and Zakariyyā Aḥmad recorded –Zakariyyā Aḥmad and Ratība Aḥmad with Polyphon, and Najīb al-Rīḥānī and Badī‘a Maṣābnī with His Master’s Voice– during the same period, a few months apart at most. The concept is inspired from French stories where a young man bothers a young girl…etc.: Najīb al-Rīḥānī’s version includes French words and elements borrowed from French stories, while Zakariyyā Aḥmad’s version bears an oriental character with the young man apologizing from the girl after bothering her. Najīb al-Rīḥānī was accompanied by what Ḥayāt Ṣabrī, in Cairo’s 1932 Congress of Arab Music, called the “orchestra” –that also accompanied Sayyid Darwīsh– including a violin, a piano, and a flute, whereas Zakariyya Aḥmad, except for some rare experiments, was always accompanied by a takht. We will note, after listening to the version of “Burrīh min el-afandiyya” recorded by Najīb al-Rīḥānī on one record-side, and Zakariyyā Aḥmad’s version recorded on two record-sides, the dialectic that started in the mid-19th century and lives on until today, including the evolution, adaptation…etc. Najīb al-Rīḥānī applied to the letter what I just talked about, while Zakariyyā Aḥmad applied the other theory… And both are ok.

Let us listen to both.

Ok…

(♩)

We know about thunā’ī (duos) from newspapers and books. What is the first thunā’ī recording we have?

The first recording we have is a parody, where he surely did not mean to vex Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī, in a comedy based on Romeo and Juliet –i.e. the peak of tragedy– and where only Romeo, out of the two, is supposed to sing. The recording includes mostly acting, not singing. It is the first thunā’ī recording that includes singing.

Between whom and whom?

…Between Aḥmad Fihmī al-Fār and another whose name is not written.

When was it recorded?

…In 1905 with Zonophone…

(♩)

Two years before WW1, Meshian recorded the duo formed by Sitt Almaẓ –spelled Almas on the record sleeve– and Rāḥmīn singing zaffa “Yā ṭal‘at al-badr” in the traditional ‘ālima style… Of course, this bears no relation to the singing theatre.

But is it a dialogue?

It is not a story, but rather a zaffa where they answer each other.

Is our discussion about dialogues in a story, or dialogues in general?

This is indeed a dialogue that might have been taken from the popular bands who played wedding zaffa and included ‘ālima and singers together. The singing in the disc I am referring to is accompanied by a takht.

Can we listen to it?

Yes…

(♩)

Dear listeners,

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

We will meet again in a new episode to resume our discussion about Musical Dialogues.

This episode was presented to you by Mr. Kamal Kassar.

“Durūb al-Nagham”.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)