Henry Farmer was born in 1882 in Birr Barracks in the village of Crinkle in what was then known as King’s County (now County Offaly) in Ireland where his father, also Henry George, served in the Leinster Regiment. Young Henry’s education started at the Regimental School in Birr and music lessons were soon underway. By the age of ten he was playing the violin with his older sister in concerts which received favorable reports in the local newspaper.

At the age of 13 on a visit to London, Henry went with his father to a Sunday afternoon concert given by the Royal Artillery Band. With this event that he made up his mind there and then that he would become a bandsman, and he got his wishes in March 1896 at the age of 14 when he became ‘Boy Farmer’, playing clarinet and violin. He was an ambitious lad, however, and hoping to get out of the back row of the second violins, he took lessons on the horn privately.

Before moving to Glasgow he had joined the Amalgamated Musicians’ Union and from then on was active in union matters. Farmer took over the editorship of the Union’s journal from 1929 until 1933. He was also one of its main contributors although he used a variety of pseudonyms to hide this fact, presumably so that he would not appear to have taken over the whole enterprise.

Another indication of his concern for his fellow workers was the setting up of a fund to raise money to help musicians and their dependants in times of illness and other difficulties. This Scottish Musicians’ Home and Orphanage Fund later became the Scottish Musicians’ Benevolent.

These were the early days of the BBC and as a member of the Musicians’ Union’s executive committee, Farmer was involved in negotiating terms for musicians who played for broadcasts. In 1918, Farmer formed the Glasgow Symphony Orchestra with the idea of performing concerts in the Glasgow parks on Sunday afternoons. He also formed ‘Dr Farmer’s Sax Band’ for the same purpose.

William Reeves, who had published Farmer’s work on the Royal Artillery Band, wanted to produce an English translation of a work by Francisco Salvador-Daniel called La musique arabe, a subject about which very little had been written in English. Farmer was already interested in Francisco Salvador-Daniel, director of the Paris Conservatoire, who was involved in the uprising in Paris at the time of the Paris Commune; the Paris Commune was one of the numerous movements which Farmer had studied, and indeed on which he had already published a series of articles in 1911. Farmer was commissioned to translate this work on Arab music and provide notes on it. He started research into the subject and soon realized that there were many conflicting theories amongst the experts. He was not happy with this. He resolved that he must study Arabic so that he could go back to the sources for himself – and so began his long association with Glasgow University. Firstly he studied as an external student and then as an undergraduate; and in 1924 he obtained his master’s degree. He proceeded with research and received his doctorate in 1926 with his thesis, A Musical History of the Arabs. There followed numerous books and articles relaying the fruits of his studies.

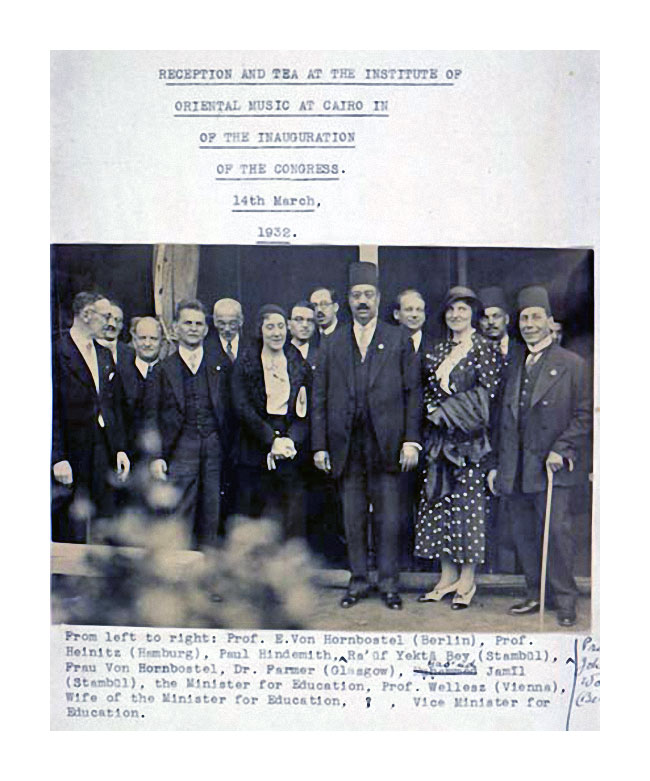

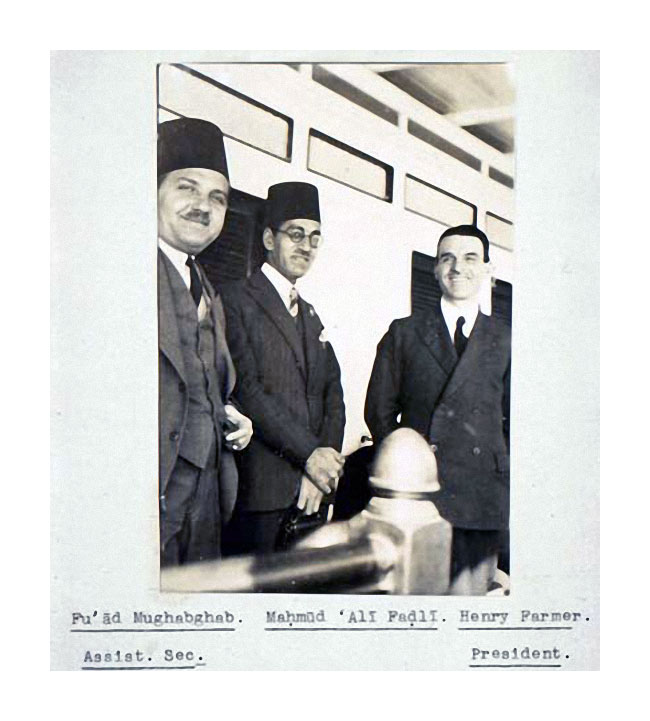

This line of study before long earned him an international reputation. Indeed, when a conference on Arab music was set up in Cairo in 1932, Henry Farmer was the only participant from the United Kingdom. At the conference he was appointed president of the Commission of Manuscripts and History. His journal shows that he was his usual industrious self, making full use of his time in Egypt – conferring, visiting and listening.

In a 1990 journal article, the Arabist scholar S. Burstyn wrote ‘For some fifty years … Farmer flooded the musicological literature with studies of Arabic music and its contribution to Western music … From a distance of six decades, Farmer still impresses with his powerful, often insightful advocacy of the “Arabian influence” thesis … ‘. While certain academics have reservations about some of Farmer’s conclusions, there is no doubt that he was a significant figure in this discipline. Despite all these achievements, Farmer never managed to finish what he described was to be his magnum opus, ‘a fully documented history of Arabian musical instruments, with special reference to their influence on the music and culture of Mediaeval Europe …’. He worked on the project for some twenty years, devoting himself to it after his retirement from the Empire Theatre in 1947. Various translations and analyses of Arabic texts did appear as a result of all this research but the work was never completed – perhaps because of the complications of trying to classify hundreds of instruments from various regions of the Arab countries. In the Farmer Collection here are numerous drafts which demonstrate his attempts to get to grips with this aim.

Farmer was also a zealous supporter of Scottish music. One outcome of this enthusiasm was the inauguration in May 1936 of the Scottish Music Society; this aimed to compile, edit, publish and distribute compositions and books on music relating to Scotland, and to arrange lectures on the subject.

The culmination of Farmer’s research on the Scottish music scene was the publication in 1947 of his A history of music in Scotland, which is a mine of information and still an essential source for anyone interested in the subject.

An expert ethnologist who is also a popular musician is news’. The ‘ethnology’ tag came from not just his music researches but the work he carried out during World War Two on artifacts which had been damaged when Kelvingrove Museum and Art Gallery was hit by bombs.