Almost eighty-five years have passed since the publication of the first volume of Baron d’Erlanger’s book “Arab Music” that has since then become a classic, an indispensable work to learn and study Arab Music in general.

This huge project is in two main parts: volumes 1 to 4 include the French translation of the principal treaties on Arab music; volumes 5 and 6 compile the entire theoretical knowledge on the contemporary Arab World of the 20th century’s second quarter.

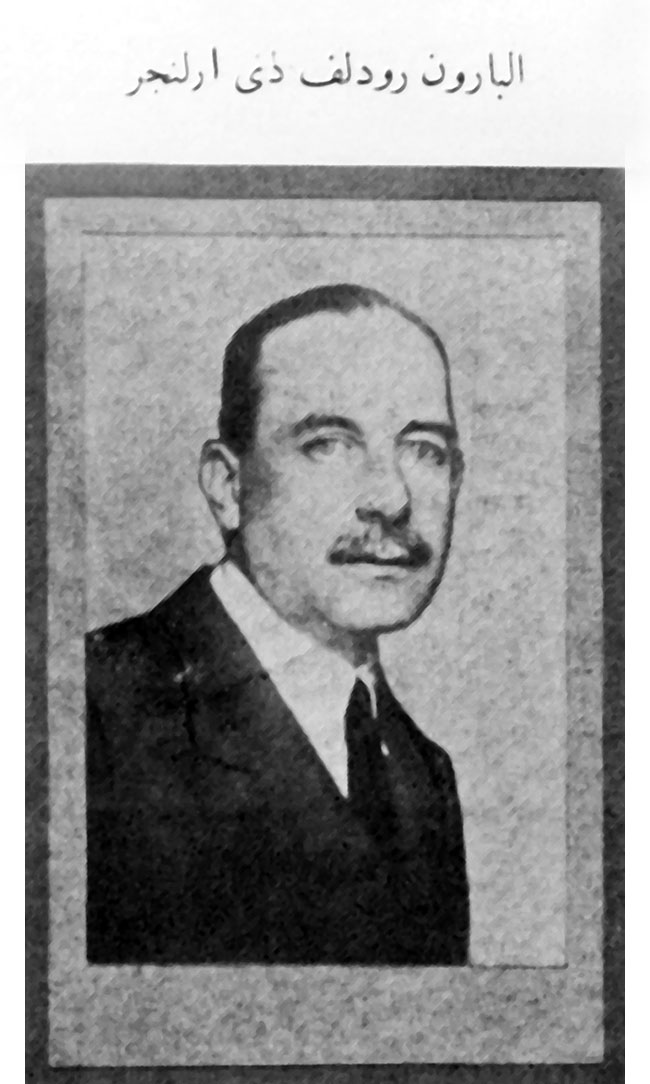

Rodolphe d’Erlanger, born on June 7th 1872 in Boulogne to a wealthy family of bankers of French and English Catholic upbringing, was captivated by the Arab World from an early age. He travelled many times to Tunisia and Egypt between 1903 and 1905 in order to paint, and thus appears to be more of an artist than a researcher. Far from being a traditionalist, he was rather a modernist who borrowed western technical means that he considered would enliven the Orient without risking to deform it. D’Erlanger was first and foremost a remarkable painter –a portraitist mainly– whose paintings bear no relation to the orientalist school.

He was also a shrewd collector: he gathered musical instruments some of which he had collected in Sub-Saharan Africa and that would later constitute the cornerstone of the Centre of Arab and Mediterranean Music’s museum. Yet he also left a library that includes all the works on Arab music published during his era.

He did not settle in Egypt but chose Tunisia where his family was already well-established, maintaining credit relations with the beylical authority and financing investment projects. Young d’Erlanger was thus well connected in this country and obviously welcome there. His first music mentor, Aḥmad al-Wāfī (I850-1921), a member of the Shādhiliyya order and an authority in music, guided and initiated him into the arcana of his art. This friendship started in 1914 and ended in 1921 upon the death of Aḥmad al-Wāfī who had introduced d’Erlanger into the brotherhoods milieux where the prevailing music was this popular music élan, the “ma’lūf al-jidd” consisting in nubah that, far from being in a state of decline like the profane learned art nubah, were in full vivacity.

He encouraged practitioners: through Al-Wāfī, he organized private concerts, presenting an array of musicians of different horizons over a period of twelve years. He also encouraged the preservation of the small instrumental ensemble called jawq in Tunisia and that will blossom into the ensemble he will form himself by choosing each of its five members in order to participate in the 1932 Cairo Congress. In this ensemble, the solo singer led his action to the octave of the other voices in the ensemble, following a technical process known in Tunisia as “ṣawt al-tays” or «voice of the billy goat».

In 1929, he made with the Tuaregs in the Sahara a series of recordings (15 galvanos) that he offered to the Berliner Phonogramm Archiv and that were later registered to his name in the German capital. He published in 1917 his first article in the Tunisian magazine “De la musique arabe en Tunisie” (Arab Music in Tunisia).

The translation of Al-Fārābī’s “Kitāb al-mūsīqī al-kabīr” started in 1922, probably when he hired ‘Abd al-‘Azīz Bakkūsh, translator on an episodic basis, and Manūbī al-Sanūsī who became his permanent personal secretary. In 1923, the work plan was set: “Arab Music” would consist in the treaties of Al-Fārābī, Ṣafī al-Dīn, Al-Lādhiqī, as well as “the Unknown”. The only missing treaty in the project’s summary then was Avicenna’s. Moreover, volumes 5 and 6 were not yet formulated nor cited in the foreword of volume 1 of “Arab Music” that appeared in 1930. Their outline was later drafted at the instigation of the 1932 Cairo Congress. This international meeting disrupted the life of the Baron and redirected his plans.

The Paul Geuthner General Catalogue of Books (Paris 1928-1931) announced from 1928 the publication of “Arab Music”. However, the project as displayed shows that d’Erlanger restructured his objectives many times.

The idea of the Cairo Congress has always been attributed to Baron d’Erlanger: a hasty conclusion and a wrong path. If the idea itself of a Congress had ever sprouted in the mind of one person, it can nevertheless not be attributed to a specific person, this would be presumptuous. If it must be attributed to the king out of diplomacy, yet it was mostly the result of the musical effervescence that bubbled in Egypt since the 1923 revolution. This unrest was fuelled by modernity and by the theoretical quarrels that divided fiercely the experts who focused on the fundamental scale of Arab Music without ever reaching a final or satisfactory solution.

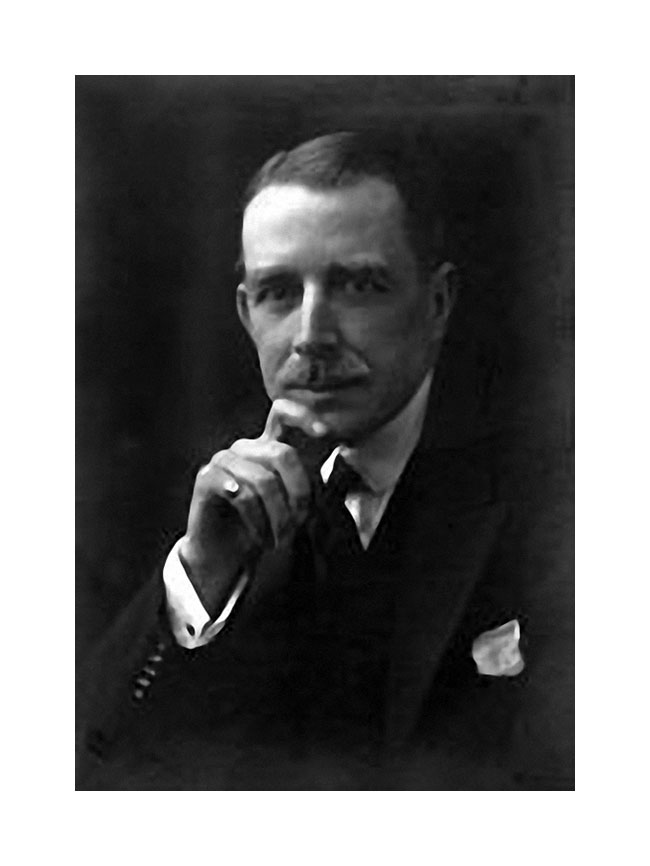

This same year 1930 when the first volume of the “Arab Music” was published in Paris was a decisive year for d’Erlanger. His name from then on tied to Al-Fārābī’s appeared in the firmament of the research and it is probably crowned with this title that he upset all the data. He also responded to the invitation of King Fuad in person. In January 1931, Rodolphe d’Erlanger had to go to Cairo where he stayed for one month. He was unofficially asked to prepare the Congress. During his stay in Cairo, the Baron met ‘Alī Darwīsh whose reputation was already well-established, and whose proficiency was indisputable. With the consent of the Egyptian authorities, ‘Alī Darwīsh landed in October 1931 in Sīdī Bū Sa‘īd where he stayed until March 1932 then went back to Cairo to attend the opening of the Congress.

During the six months he spent at the Baron’s home in Sīdī Bū Sa‘īd, ‘Alī Darwīsh’s mission consisted essentially in writing several reports, including one about rhythms that was published in Arabic under the name of Baron d’Erlanger in a book compiling the works of the Cairo Congress, in 1933 and 1934, in both an Arabic and a French version of the proceedings. At that time, the state of health of Rodolphe d’Erlanger worsened. The speech he had prepared for this occasion was not even read. He died probably of tuberculosis or of a bronchial disease on October 29th 1932.

Christian Poché

Jean Lambert