This episode resumes our discussion about the form of the dawr.

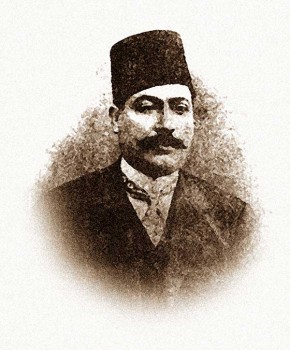

We will start it with the second generation of the Nahḍa composers, i.e. the students of Muḥammad ‘Uthmān and ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī, the two most famous being Dāwūd Ḥusnī and Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī. In his books, Kāmil al-Khula’ī named them “the young generation”. After mastering the composition of the dawr following the pattern of the Nahḍa’s first generation, i.e. the pattern followed by ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī and Muḥammad ‘Uthmān (founders of the Nahḍa school) who mastered the composition of the dawr to this pattern, they developed it. According to Al-Khula’ī, the young generation believed it was possible to find new ways to develop this rich form. They adopted the concept of the set pattern fixed by ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī and Muḥammad ‘Uthmān, and developed it until it included all the passages of the dawr. The madhhab remained the same, with more focus on the maqām and the option to compose instrumental phrases with shifts between different melodic aspects. The dawr’s structure with all its passages now followed a certain order. The tafrīd became partially improvised: there was now a melodic thread as well as shifts suggested by the composer to the performer, thus giving the latter a chance to exploit his talent. Yet, some performers added their own variations such as Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī, while others performed these variations literally such as Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī. Others used to disregard them completely and perform at whim such as ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Afandī Ḥilmī. The waḥāyid passage now replaced the āhāt and the layālī (the tarannum or the henk) right after the tafrīd, followed by the responsorial part, then the conclusion, the āhāt kept before the conclusion, i.e. the long breath. That does not imply the cancellation of the singer’s improvisations and spontaneous articulations, on the contrary, this pattern may have inspired the performer to come up with new variations.

This period witnessed the spreading of the recording concept. These two composers were not known as singers, yet we chose to give examples of their works sang by them even though they usually had their adwār recorded by other singers as well as performed by those during their concerts. This period also witnessed the emergence of the lyricists’ and composers’ copyrights.

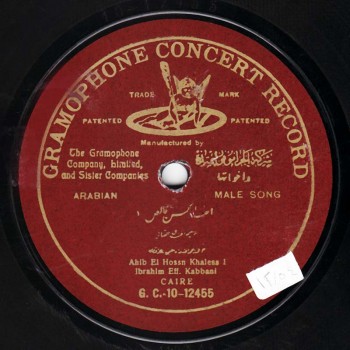

Let us first listen to dawr “Aḥibb el-ḥuṣni khālaṣ” to the rāst maqām, nawrūz sub-maqām. This dawr illustrates perfectly the characteristics of the set pattern, yet it also shows the performer –also the composer- proving that this pattern is not unshakable by surprising the takht with spontaneous improvisations. Speaking of the takht, this is one of the first recordings featuring all the takht members. As the early 20th century recordings made in front of the brass horn could not convey the sound of all the takht instruments, the nāy and the riqq are barely heard in this recording. The takht includes Ibrāhīm Afandī al-Qabbānī (‘ūd), Muḥammad Afandī Ibrāhīm (qānūn), Sāmī Afandī al-Shawwā (kamān) ‘Alī Afandī ‘Abduh Ṣāliḥ (nāy) and Muḥammad Abū Kāmil al-Raqqāq (riqq). The recording was made by Gramophone around 1909 on four 25cm record sides, order # G.C.-10-12455, G.C.-10-12456, G.C.-10-12457, G.C.-10-12458, matrix # 11944 B, 11945 B, 11946 B, 11947 B.

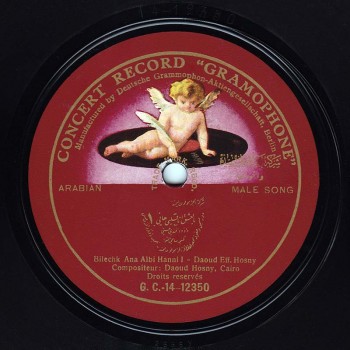

Note that the melody’s pattern includes more similarities than disparities, to such an extent that we can actually affirm that Ibrāhīm’s composing style and Dāwūd’s are so close that they sometimes are exactly the same, as it is impossible to talk about the simplicity of a melody or the precision of an art in the same way we talked earlier about Al-Ḥāmūlī and ‘Uthmān. Yet, the surprise is that Al-Maslūb whom we said followed the pattern of the Nahḍa’s first generation also followed the development instigated by the second generation. Dawr “El-ward fī wagnāt bahīyy el-gamāl” is one of his adwār during this phase. But we will not listen to it as we have listened to enough recordings by Al-Maslūb during the last episode. We will listen though to a sample composed by Dāwūd Ḥusnī: dawr “Bi el-‘ish’ anā albī hānī” illustrating the concept of the pattern and the arrangement of the dawr’s elements: a madhhab, then a tafrīd, then a tarannum starting off the waḥāyid, followed by the responsorial part then the conclusion. The dawr is to the jaharkāh maqām recorded on four 25cm record sides, made by Gramophone around 1912, order # G.C.-14-12350, G.C.-14-12351, G.C.-14-12352, G.C.-14-12353, matrix # 2666 Y, 2667 Y, 2668 Y, 2669 Y. The takht includes Dāwūd Ḥusnī (‘ūd), Sāmī al-Shawwā (kamān), ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī (qānūn) and Muḥammad ‘Alī Li’ba (riqq).

Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī was among those who followed Al-Qabbānī and Ḥusnī, but his tendency towards the singing theatre led to diminish the number of his adwār whose quality never faltered. Yet, the generation that followed the generation of Al-Qabbānī, Ḥusnī and Ḥigāzī excelled in both adwār and the musical theater, such as Sheikh Sayyid Darwīsh, Sheikh Zakariyyā Aḥmad and Muḥammad Afandī ‘Abd al-Wahāb. The way they dealt with the form of the dawr was different, as the way Al-Qabbānī and Ḥusnī dealt with the form of the dawr was different from the one of their predecessors.

We will discuss this difference in the third and last episode about the dawr.

Thank you for listening.

We will meet again in a new episode of “Our Musical System”.

This episode was brought to you by Muṣṭafa Sa‘īd.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)