Amar Foundation presents: Men Al-Tarikh

Mustafa Said: Welcome to a new episode of Men Al-Tarikh. Today, let’s continue with His Highness Frederique Lagrange Pasha talking about Sheikh Zakariyya Ahmed and El-Sett Om-Kolthoum.

Frederique Lagrange: [Joking], Thank you very much for the Pasha title, yet, by the way, where’s my fezz? You promised to get me a Fezz.

M:[joking], I’ll get you one next time.

F: Thanks, thanks.

M: [serious], Your highness, despite the delay of Sheikh Zakariyya’s recording with Om-Kolthoum until 1931, he had previously, in his youth, met her.

F: We’re very lucky that Sheikh Zakariyya Ahmed used to write everything he did. He used to keep a diary so the date and time of everything he did was written precisely. It seems that Sheikh Zakariyya Ahmed was singing in a party in El-Simbellawein in June 1919, and El-Sembellawein is so close to Tamai El-Zahayra that it’s now almost one of its suburbs. He heard her singing with her brother Khalid so he visited her in Tamai El-Zahaira. 1919 means that Om-Kolthoum was not a child, she was anyway a teen-ager between 17-19 years old as her date of birth is not precisely known. He also was still somehow young as he was born in 1896.

M: Ok man, but do you think that the question of the contracts with the recording labels was the reason why the collaboration between Sheikh Zakariyya and the then Ms. Om-Kolthoum was delayed?

F: It’s a very excellent idea. As of the 1920’s, the recording labels acted like a ruler in the music scene. I think, then, that the artistic director of the recording label was the one to decide who works with whom in the recorded music. It’s most likely, then, that the recording labels had a role in initiating this partnership which began, I think, in 1931 between Sheikh Zakariyya Ahmed and Om-Kolthoum. This is a very likely assumption. You know that there were exclusive contracts between the artists and the recording labels. So, probably, when Sheikh Zakariyya signed a contract with Polyphone, Baydaphone or Homocord, Om-Kolthoum, on the other hand, may have signed a contract with His Master’s Voice, Odeon…..etc at the same time. There was no possibility, then, for any of them to collaborate with the other because the contracts prohibited this. This is just an assumption of course, we don’t want to tell guesses, but it’s a very likely hypothesis.

M: especially that the songs were then sold to the recording labels and not to the singers.

F: Exactly.

M: As the recording labels were the buyer, it was them who specified who would sing what.

F: We can divide the collaboration between Sheikh Zakariyya Ahmed and Om-Kolthoum into several periods: First, the 1930’s and before the movies. One of the rather strange characteristics of this period was Sheikh Zakariyya’s insistence on using the Dawr form, and despite the fact that the Dawr, as a form, was fading out of fashion as of the late 1920’s, he composed Dawrs for her until the mid 1930’s. Unfortunately, we know nothing about the extent of similarity between Om-Kolthoum’s recordings of these Dawrs and how she used to live perform them, unlike the case before the 1920’s. The period between 1920-37 was like the Bermuda Triangle for the Arab music because, before 1920, the music recording industry was trying their best to reflect the real singing scene by imitating the manner of the public concerts. Of course, they couldn’t record in public concerts as the recording technology then wasn’t able to do that, yet the singer was able to present a brief image to what he was supposed to do in a concert. So, a dawr could have been recorded on 2, 3 or even 4 sides as an attempt to give a rather true, though distorted, image of the real performance. After 1920, however, the recording industry forced its ideals on the music production so that the final product would be absolutely a recorded performance, almost completely separate from live performances for the pieces in public concerts.

M: [commenting], as an example.

F: Exactly.

M: not any more a reflection.

F: Exactly, an exemplary image of a musical piece. Why I used “Bermuda Triangle”? Before 1920, we have a distorted image of the musical scene. After 1937, and with the invention of the magnetic wire, it became possible to record the public concerts. Even though these recordings are rare and as little as the fingers of both hands, or let’s say that there’re around 30 concert recordings in the late 1930’s and early 1940’s, these recordings give us a good idea about the Egyptian live music scene in this period. Between 1920-37, however, there’s nothing.

M: The isthmus of the recording industry.

F: Exactly, an isthmus. We had no idea about how the musical heritage of this era, i.e., the musical compositions were performed in real life. Let’s go back to Sheikh Zakariyya Ahmed. Zakariyya Ahmed, for an unknown reason, seemed very passionate about the Dawr form, I wouldn’t say because of the traditional nature of the Dawr, but, probably thanks to the open area for improvisation it gives to the singer, as well as the possibility to interact with the audience. This is a very important characteristic of Sheikh Zakariyya Ahmed. He composed Dawrs for himself like Inta Fakir and Meseer Aqlak, and he composed Dawrs for Om-Kolthoum which are considered some of the best.

Layla Murad

M: Also for Sett Layla Murad.

F: and for Sett Layla Murad.

M: But do you think that he made these Dawrs really for himself? I mean the three Dawrs he recorded with Odeon Records Inta Fakir, Mseer Aqlak and El-Fuad Leiloh We Naharoh.

F: Had there been for others, we have no commercial recordings for them by others or even advertised concerts in which they were supposed to be sung. Of course, there’s this famous recording from El-Tabii’s collection in which Layla Murad sang a short extract of Mseer Aqlak in which all of the attendants were repeating noisily, so the Dawr came sadly, I cannot say distorted, but, not in its best shape.

[Listen to Layla Murad singing with Sheikh Zakariyya Ahmed Dawr Mseer Aqlak in a private session.].

F: His compositions for Om-Kolthoum were aesthetically conservative as he did neither follow El-Qassabgi’s steps nor those of Riyad El-Sonbati later on. It’s clear that he was completely saturated by the renaissance school and he was an advocate to its aesthetic principles. Additionally, he gave Om-Kolthoum a chance to show her capabilities to sing in a traditional Arab musical style in non-traditional forms. We were talking about Dawr, but these Adwar are considered void as we actually know nothing about them other than the fact that they were recorded and that they were really beautiful like Meen Elli Aal and Imta El-Hawa and many others.

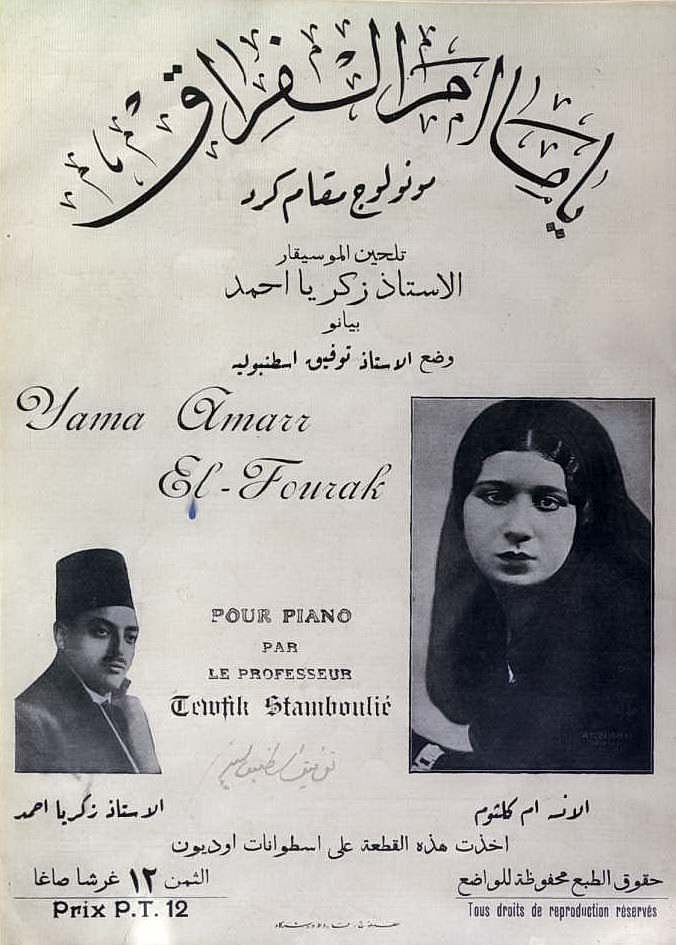

M: Before we go to the post-Adwar era, be it cinema or long songs which I view, especially with Sheikh Zakariyya, as a continuation of the Adwar, -something that we can discuss later- let’s stop by the Adwar, the Adwar composed by Sheikh Zakariyya to Om-Kolthoum. All of them were recorded on two sides, all were recorded with Odeon records, some of them were on 30CM discs and others were on 25CM discs, these were the compositions of Sheikh Zakariyya.

F: Let’s listen to Meen Elli Aal.

M: be it Meen Elli Aal, how wonderful.

[Now listen to Dawr Meen Elli Aal composed by Sheikh Zakariyya Ahmed and sung by Om-Kolthoum.].

M: Who’s the lyricist ya Sayyidna?

F: An unknown lyricist called Abdul-Rahman Fayyad. Some of the Adwar composed by Sheikh Zakariyya to Om-Kolthoum were written by Ahmed Rami, one of them was written by Badi’ Khayri Huwwa Dah Yekhallas min Allah.

M: Almost her first Dawr with Sheikh Zakariyya, isn’t it?

F: Yes, I think so. It was in the very early 1930’s, 1930 or 31. This is something that can be determined by the Matrix numbers.

M: Was the Dawr actually made especially for the recording label or was it sung live first and then recorded by the recording label?

F: I think that these Adwar were directly recorded by the recording label because, when we look through the catalogs, they were often mentioned as “Recorded Dawr” and the word “recorded” means “commercially recorded”. The recording labels used to pay for the lyricists and musicians to produce new songs. Then came the problem of who had the right to perform these musical pieces. As for Om-Kolthoum’s dawrs, it was allowed only for her to perform them live at least in the big cities. We all remember what happened to Munira El-Mahdiyya when she tried to sing the monologue entitled In Kont Asamih Wansa El-Aziyya, and though she changed the Maqam not to appear as trying to imitate Om-Kolthoum, Gramophone records sued her as she had no right whatsoever to sing Om-Kolthoum’s songs in public concerts without a prior permission from the company itself. So, I think that no one else but Om-Kolthoum herself sang these Adwar except, possibly, secondary singers or even famous singers sang these Adwar but in private sessions not in public concerts. It was not possible for any other performer to sing these Adwar in concerts in Cairo, Alexandria or in other big cities.

M: I didn’t mean by my question to ask whether or not someone else had sung them before Om-Kolthoum recorded them. I meant to ask whether or not Om-Kolthoum had sung them before recording them.

M: I didn’t mean by my question to ask whether or not someone else had sung them before Om-Kolthoum recorded them. I meant to ask whether or not Om-Kolthoum had sung them before recording them.

F: I think they were recorded first. If you mean whether or not she tried them in front of the audience first, I didn’t think she did. The record often came first. It was a commercial trick. One could listen to the song in a concert and then got the record directly from the recording label. Of course, it would have been a total disappointment as one would have heard a song in a concert and what he would find on the record was a totally different version, i.e., the exemplary version we talked about before.

M: It’s known that in all the Adwar, with very few exceptions, the Mathhab is in Masmoudi Rhythm and then goes to the Wahda rhythm for the Wahayid part, Tarannum (chanting), Mugawba (responsive part) and final Sayha (yelling) at the end of the dawr.

F: I know where you want to take us! You want us to talk about the Dawr recorded by Om-Kolthoum which contains a Dawr-Hendi rhythm Mathhab. Dawr-Hendi has no relation with the Dawr as a term, it’s the name of a traditional Arab musical rhythm.

M: Yes, it’s a 7 beats rhythm. Dawr Yalli Teshki mel-Hawa has a very beautiful rhythmic variation starting with Dawr-Hendi I the Mathhab, then the Wahda rhythm, and finally Darig rhythm in the Ahat and Mugawba parts, an unusual variation in the Dawr as even when they went off-beat, they kept to the same rhythm. This Dawr Yalli Teshki Mel-Hawa, however, has a rhythmic variation on the one hand, and on the other hand, it contains very beautiful instrumental responses. It’s in Nagham Dugah, Maqam Baya-Nawruz or Bayyati Nawruz, recorded like Meen Elli Aal with Audion Records but almost two years before it. Dawr Meen Elli Aal was part of the movie Widad in 1935, and this one was recorded almost in 1933.

[Listen to Dawr Yalli Teshki Mel-Hawa composed by Sheikh Zakariyya Ahmed and sung by Om-Kolthoum.].]

[End of the third Episode.].

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)