The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Sama‘ ”.

“Sama‘ ” discusses our musical heritage through comparison and analysis.

A concept by Mustafa Said.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Sama‘ ”.

Today’s episode is about qaṣīda “W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak wa-lā urīdu al-ḥayāta ba‘dak” (By God I can’t reject you, nor can I bear living without you) written by Sheikh ‘Abd al-Lāh al-Shabrāwī, composed and sung by Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥāmmad, and recorded by Baidaphon in 1921, then recorded again by Odeon six years later in 1927 in the voice of Fatḥiyya Aḥmad.

We will be discussing these two recordings:

-

Abū ‘Ilā Muḥammad’s recording belongs to the last generation of analogically printed and recorded recordings.

-

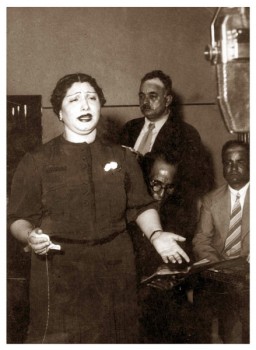

Sitt Fatḥiyya Aḥmad’s recording is among the early electrical recordings.

Both are 27cm records, yet Sitt Fatḥiyya Aḥmad’s recording is a little less than one minute longer than Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā’s.

Let us discuss the poem:

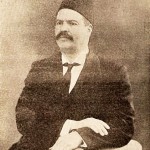

Qaṣīda “W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak” was written by Sheikh ‘Abd al-Lāh al-Shabrāwī, seventh Imām and Sheikh of the Azhar Mosque, born in the late 12th century Hijrī –late 17th century A.D– who had become a Sheikh in the 13th century Hijrī –18th century A.D–.

We consider the period of the Turkish Emirs, the Jarākisa (Circassian), and the Ottomans, as a period of Arabic literature decadence. Nevertheless, Sheikh ‘Abd al-Lāh al-Shabrāwī was truly a poet who wrote beautiful, abundant, and easy poetry… a finely written rich dīwān as valuable as that of great poets. He also authored numerous writings on fiqh shāfi‘ī and belief, as well as on linguistics, added to one or two books on ‘Arūḍ (Arabic prosody).

This qaṣīda is to the mustaf‘ilun fā‘ilun fa‘ūlun meter, categorized as a mukhalla‘ basīṭ:

The baḥr basīṭ is mustaf‘ilun fā‘ilun mustaf‘ilun fā‘ilun. When it is mukhalla‘, it becomes mustaf‘ilun fā‘ilun fa‘ūlun. Mr. ‘Abd al-Lāh al-Shiddī told us that the poet wrote this qaṣīda after reading verses written by Aḥmad Ibn Ḥajjāj al-Baghdādī who was not satisfied with Al-Khalīl Ibn’s categorisation, and said:

mustaf‘ilun fā‘ilun fa‘ūlun / masā’ilun kulluhā fuḍūlu (odd issues)

Qad kāna shi‘ru al-wara ṣaḥīḥan / min qabli an yukhlaq al-Khalīliu (Creative poetry was correct before al-Khalīl was born).

He created this qaṣīda based on these verses.

Poetry to the baḥr mukhalla‘ basīṭ is full of music, easy, abundant, and always on people’s tongues.

We will recite the verses of the qaṣīda as they are in the dīwān.

We thank Mr. Fadil al-Turki for his analog writing of the qaṣīda.

He says in the dīwān:

He, God protect him, said:

And I –‘Abd al-Lāh al-Shabrāwī– also said, lovingly:

W-Allāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak Wa-lā urīdu al-ḥayāta ba‘dak

Yā qātilī hal fa‘altu dhanban Yūjibu hādhā al-ṣudūda ‘indak

Bi-al-Lāhi bi-al-Lāhi yā ḥabībī Wa‘adta bi-al-waṣli waffi wa‘dak

Fa-lī fu’ādun yadhūbu shawqan Ilayka mahmā dhakartu bu‘dak

Jarra‘tanī al-hajra wa-huwa murrun Wa-ṭālamā qad rashaftu shahdak

Wa-khunta ‘ahdī fa-layta shi‘rī Hal khuntu fī al-‘āshiqīna ‘ahdak

Man munṣifī minka yā malīkan Ṣayyarta kull al-milāhī jundak

Wa-laysa lī fī al-milāḥi khaṣmun Siwāk lākinna mā aladdak

Wa-laysa lī fī al-milāḥi khaṣmun Siwāk lākin mā aladdak

Shārakanī fīka kullu ṣabbin Lammā ḥawayt al-jamāla wahdak

Wa-qad ashā‘ al-‘adhūlu annī Mushabbihun bi-al-ghuṣūni qaddak

Wa-anta ‘indī ajallu min an Yushbiha wardu al-riyāḍi khaddak

Wa-lastu yā badru artaḍī an Yuṣbiḥa badru al-samā’i ‘abdak

Yā ghuṣnu qad milta ‘an mu‘annan Li-qalbihi fī al-hawa a‘addak

Yaqṣuru yā ghuṣnu ‘anka bā‘ī Jall al-ladhī bi-al-jamāli maddak

Yā hasbuk al-‘Lāh yā ghazālan Ghazawta bi-al-muqlatayni usdak

Tahgurunī ghāzilan wa-lākinna Hazlaka bi-al-hajri fāqa ḥaddak

Wa-qātala al-Lāhu fīka ṭarfī Huwa al-ladhī qad aḍā‘a wajdak

Fa-lā rā‘a al-Lāhu fīka qalbī Fa-kam bihi qad balaghta qaṣdak

Wa-anta yā ‘ādhilī taraffaq Fa-qad ta‘addayta fiyya ḥaddak

Ta’muru bi-al-rushdi mustahāman Ya‘uddu ‘ayn al-ḍalāli rushdak

Kun kayfamā shi’ta yā ḥabībī La kāna man ‘an hawāka raddak

Wa-hjur idhā shi’t aw fa-wāṣil Wa-tih dalālan ‘layya jahdak

Fa-lastu w-al-Lāhi akhtashī min Sha’n siwa an adhūqa faqdak

These are the verses in full as they are in the dīwān, knowing that most of the lyrics were sung.

There is an anecdote about the verse “Shārakanī fīka kullu ṣabbin / Lammā ḥawayt al-jamāla wahdak” being pronounced “Shāraktanī fīka kulla ṣabbin / Lammā ḥawayt al-jamāla wahdak”.

There isn’t much to explain in the qaṣīda: the lyrics are simple and understandable. Yet, there might be some ambiguity relatively to poetic necessity at the end of the verse. And, in fact, the last verse “Fa-lastu w-al-Lāhi akhtashī min / Sha’n siwa an adhūqa faqdak” was not sung.

“Min sha’n” means “min shay’in” (from something) out of which he removed the “y” to be compatible with mustaf‘ilun fā‘ilun fa‘ūlun.

Besides this, the lyrics are very clear.

It can convey different meanings depending on whether it is ghazal ṣūfī or ghazal ‘afīf. (I think it is ghazal ṣūfī).

Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad chose the maqām ṣabā. We have explained that the maqām ṣabā was initially the maqām ṣabāḥ from which the “ḥ” was removed because it does not exist in the Turkish alphabet nor in the ‘ajamī alphabet. It first became ṣabāh with an “h”, then the “h” was removed and it became ṣabā. Then there was a mix-up with adhān al-ṣubḥ (morning prayer) that was sung to the ṣabā maqām, and as we know “each moment has a adhān”. We talked about this during our discussion about the maqām ṣabā.

The point is that the maqām (musical key) is the ṣabā.

Let us talk about the octave…

Relatively to the instruments:

-

Sheikh Abū al-‘īlā Muḥammad sings one fourth higher than Sitt Fatḥiyya. The violin plays ascending starting from the third string. In Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā’s recording, it is the nawā string, and the jawāb yakāh, or according to the old categorisation, under the zīr, there is the mathna.

-

With Sitt Fatḥiyya, he plays ascending starting from the second string, i.e. the dūkāh or the fifth of the first string, or the mathlath according to the old categorisation, that is right before the bamb. So, we have: the zīr, the mathna, the mathlath, then the bamb, on the ‘ūd, or the violin in this case. The same applies to the qānūn.

Let us listen to the dūlāb, i.e. Abū al-‘Ilā’s introduction …

(♩)

And the dūlāb in Sitt Fatḥiyya’s recording …

(♩)

The sound is clearly thicker, which implies that the octave is lower.

Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad sings to an octave close to the high dāwūd –i.e. the middle or minor dāwūd, not the major dāwūd– on the nāy.

Sitt Fatḥiyya Aḥmad sings to the women’s octave. Not exactly though, a little higher in both cases… Some would say that she sings to the yildiz or the nijma octave.

In both cases, the categorisation on the nāy is unimportant. The point is that, relatively to the instruments, Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad sings one octave higher than Sitt Fatḥiyya, whereas, on the voice level, he sings one fifth lower than Sitt Fatḥiyya Aḥmad… Knowing that a woman’s voice will surely go higher than a man’s.

This was concerning the octave …

(♩)

As we usually do with such small works, let us listen to the full qaṣīda in the voice of Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad, considered according to the record companies’ categorisation that was later imposed as the initial recording –as to the writing, singing, and composing–.

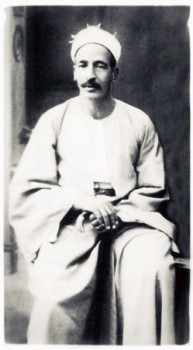

Here is Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad’s recording of “W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak” to the maqām ṣābā, written by Sheikh ‘Abd al-Lāh al-Shabrāwī, recorded by Baidaphon around 1921 …

(♩)

Beautiful Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā!

Those who wish to know more about Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā can refer to our previous episodes dedicated to him. The instrumentalists in both recordings are the same. Sāmī al-Shawwā (violin) and ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī (qānūn) who play in this recording also played in Sitt Fatḥiyya’s recording six years later. I also suspect that Maḥmūd Raḥmī plays the percussions in both recordings, yet I can’t affirm this because the catalogues, contracts, and people only mention the melodic instruments players. Very few talk about the percussionists. Let us thus just say that the percussions playing style is the same in both Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā’s and Sitt Fatḥiyya Aḥmad’s recordings …

(♩)

Let us hear the first verse in the two recordings …

(♩)

There are two remarks:

-

Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā focuses more on the language than Sitt Fatḥiyya. In “W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak wa-lā urīdu al-ḥayāta ba‘dak”, he extends the “a”, whereas Sitt Fatḥiyya Aḥmad says the first time “Wa-la urīd” as if she were cancelling the long vowel “a”, pronouncing the “w” with a fatḥa, i.e. “wa” and the “l” with a fatḥa, i.e. “la”, followed by the “ ’ ” (hamza), she does not say “wa-lā urīd” but rather “wa-la urīd”. Moreover, Sitt Fatḥiyya segments “Wa-la urīdu al-ḥayāta ba‘dak” as follows “ Wa-la urī…du al-ḥayāta ba ‘dak”, whereas Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad does not.

-

Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad concludes a second time, i.e. concludes the repetition of the first verse, with a fourth that is a little higher than the ordinary ṣabā, as if he were concluding to the Turkish jahārkāh, whereas Sitt Fatḥiyya Aḥmad concludes it to the ordinary ṣabā.

Let us listen …

(♩)

I think that Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā helped her memorise it to the ordinary ṣabā, and kept the fourth that is a little higher than the ṣabā’s fourth as a personal initiative.

We will end today’s episode with this verse and discuss the rest of the verses during our next episode.

We will meet again in a new episode of “Sama‘ ” to resume our discussion about “W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak” written by Sheikh ‘Abd al-Lāh al-Shabrāwī and composed by Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥāmmad, or rather recorded by Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥāmmad –as it is improvisation in my opinion– that was recorded again six years later by Sitt Fatḥiyya Aḥmad.

We will meet again in a new episode to talk about this work.

“Sama‘ ” was presented to you by AMAR.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)