In Arabic Classical Music, the bashraf is among the instrumental forms introducing the maqām waṣla that starts with an instrumental piece like the bashraf or the samā‘ī.

In Arabic Classical Music, the bashraf is among the instrumental forms introducing the maqām waṣla that starts with an instrumental piece like the bashraf or the samā‘ī.

The word bashraf is an interpretation of the Persian word peshrū: meaning an introduction to what will follow. It became peshrev in Turkish, then bashraf in Arabic (plur. bashārif or bashrawāt), its origin being bushra or bishāra.

Coming from the mawlawiyya samā‘ī waṣla and from ottoman court music, the bashraf reached the Arabic maqām waṣla in two forms:

First, the traditional mawlawiyya form played in ottoman court music:

Four khānāt separated by a lāzima that is equal to a khāna, to half a khāna, to a third of a khāna, or to a quarter of a khāna. The rhythm of the bashraf is usually long, such as the rhythm of the 28-pulse dawr. Thus, if a khāna equals 2 measures of this rhythm, then the lāzima may equal 2 measures or 1 measure, i.e. half a khāna. Also, the khanāt and the lāzima may end with a short phrase called taslīm that relays from each khāna to the lāzima. If the taslīm is included in the lāzima, then it relays from the lāzima to the khānāt. It can be present in all of the khānāt and the lāzima, in the khanāt but not in the lāzima, or in some rare instances, in some of the khanāt, but not all of them. The taslīm phrase does not exceed half a rhythmic measure.

Among the bashrawāt that entered Egypt is the humāyōn bashraf composed by ‘Uthmān Bēh al-Ṭanbūrī, a mawlawiyya follower who served at the Topkapi Palace in the mid-19th century. Each khāna of this bashraf includes 3 rhythmic measures of the 28-pulse dawr, and ends with a taslīm to the lāzima with 8 pulses into the last measure of each khāna of course. If each khāna includes 84 pulses, i.e. ‘adda, then the taslīm starts at the 77th ‘adda. The lāzima itself equals one rhythmic measure of the dawr’s rhythm, ie. a third of a khāna.

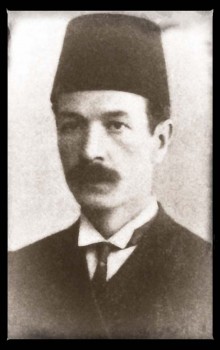

Let us listen to the humāyōn bashraf, a sub-maqām of the ḥijāz, composed by ‘Uthmān Bēh al-Ṭanburī, and performed by Muḥammad al-Qaṣṣabjī (‘ūd), Sāmī al-Shawwā (kamān), ‘Alī al-Rashīdī (qānūn), and Maḥmūd Raḥmī (percussions). Among the first electric power-printed recordings, it was made by Columbia around 1927 on two sides of a 25cm record, order # 13286 1 & 2, matrix # E 71 & E 72.

In mid-18th century Istanbul, a type of bashraf appeared that was only different from the other types in the way it was performed. Some of its parts are either played by one instrument or in a dialogue between two instruments. When it entered Egypt and the Levant, Arab musicians tended more towards variations and improvisations then towards a fixed pattern. Consequently, the concept of a pre-composed dialogue or of a unique instrument was transformed into an improvised dialogue between one musician and the rest of the instrumental band, closer to the concept of a taḥmīla inside a bashraf. We will discuss the taḥmīla form in a future episode.

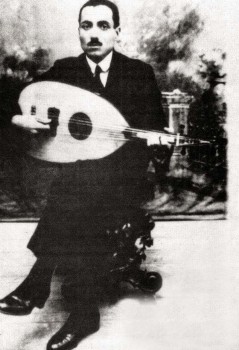

Let us now listen to a bashraf qarrah batāq sīkāh performed by Takht Odeon – the instrumental band adopted by Odeon Records for all the instrumental recordings as well as those with vocal accompaniment. The takht includes Al-Ḥāj Sayyid ‘Alī al-Suwaysī (‘ūd), ‘Abd al-‘Azīz Afandī al-Qabbānī (qānūn), and ‘Alī Afandī ‘Abduh Ṣāliḥ (nāy). This work was recorded around 1904 on 2 sides of a 27cm record, order # 31017 1 & 2, matrix # EX 952 A & B. Note the su’āl and the jawāb between the musician playing solo and the rest of the instrumental band, as well as the fluid transition between the instruments’ playing during the improvisations.

The last type of bashraf we will discuss today has no counterpart in Turkish music, no appellation, and was never observed before despite its fame. It includes only 2 khānāt and is composed to a rhythm shorter than the rhythm of the ottoman bashraf. This bashraf may have been invented in the Arabic Mashriq, in Egypt, in the Levant, or in Iraq. Its performance is based on one phrase that is repeated in two khanāt and in the lāzima as a taslīm. Yet, this phrase does not constitute a transition or a link between the parts, it has the role of a repetition. It can be performed in a certain manner signaling the repetition of some khāna, such as the first khāna for example, even after the taslīm even, or even after the end of the second khāna. It is then possible to go back to the first khāna, depending on the performers’ wish.

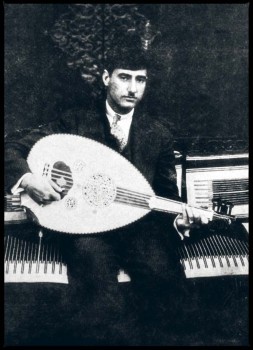

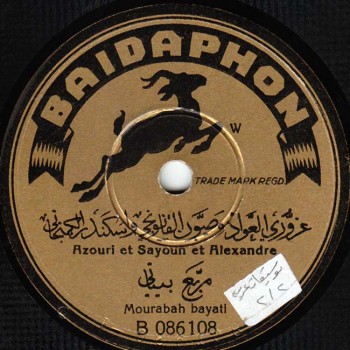

Let us listen now to a bashraf of this type, a 4-rhythmic bayyātī bashraf, i.e. to the bayyātī maqām and to a 13-pulse 4-rhythmic cycle, performed by ‘Azzūrī Hārūn (‘ūd), Ṣayyūn al-Qānūnjī (qānūn), and Iskandar al-Kamanjātī (kamān).

It was recorded by Baidaphon around 1927 on two sides of a 27cm electric power-printed record, # B-086107 and B-086108.

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Niẓāmunā al-Mūsīqī” brought to you by Muṣṭafa Sa‘īd.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)