The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

In today’s episode, we will resume our discussion about Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad with Prof. Frédéric Lagrange.

60% of Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad’s recordings were qaṣīda, many or most of them ‘ala al-waḥda. He also recorded other forms including the elements of the waṣla, muwashshaḥ, taqsīm layālī, mawwāl, dawr, and qaṣīda, as well as ṭaqṭūqa as you mentioned in our previous episode. Could you elaborate?

In Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad’s repertoire, the form ranked second after the qaṣīda is the mawwāl, which is very logical since the mawwāl can be considered as an extension… there is a link between the qaṣīda mursala and the mawwāl. This in no way implies that the qaṣīda mursala is the literary equivalent of the colloquial mawwāl as the latter’s structure may differ from the structure of the qaṣīda mursala, its melodic pattern being often ascending then descending, while there is no set rule governing the qaṣīda mursala whose structure is freer than the mawwāl’s. It is quite logical that the mawwāl form should follow the qaṣīda in Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad’s repertoire: he sang beautiful mawwāl including “Lēh el-ḥabīb ṭāl gafāh” and “Fēn yā gamīl wa‘dak”, and “Āh min awāmak” to the rāst maqām. Besides the mawwāl, the noteworthy issue concerning his repertoire is the layālī preceding the mawwāl or the dawr in the waṣla: Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad is among the muṭrib who dedicated full record-sides to layālī, and probably the only one who recorded a full disc dedicated exclusively to layālī nahāwand to the bamb, a magnificent record by Gramophone. When reading the title “Layālī nahāwand” on the record, one does not think it is meant literally, i.e. layālī implying “yā lēl yā ‘ēn”, and nahāwand being the maqām’s type. Upon reading and hearing “Layālī nahāwand”, one is magically transported far away to the Persian city of Nahāwand, and discovers layālī nahāwand. This record is a legend in itself.

Layālī ‘ala al-waḥda were often used as a continuation to a dawr for example. A full record –not just one side– dedicated to layālī is a strange thing indeed. On the other hand, doesn’t this prove that it was originally performed within the waṣla… that it is not a product of the phonograph?

There are blanks in our knowledge of this era’s music, including how a takht and a waṣla functioned: all our information comes from these discs that are the only 100% reliable source. Still, due to the primitive quality of the recording industry in the early 20th century, these records only reflect a distorted image that is not 100% reliable in reflecting the reality of music practice. And thus, concerning the layālī to the bamb following dawr or qaṣīda to fill the remaining duration on the record-side, we wonder if they were independent, or if it was possible for the muṭrib to prolong them? It surely depended on the muṭrib’s mood and on whether he felt like performing layālī for a long stretch of time. Yet, Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad being the only one during this period who recorded a full disc dedicated to layālī nahāwand may indicate either that layālī were not yet independent forms like dawr, qaṣīda or other forms, or that performing them for a long time was not usual. That is why this is an exceptional case, and an exceptional disc.

Shall we listen to “Layālī al-nahāwand”?

Ok.

(♩)

Talking about “Layālī al-nahāwand”, Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad recorded layālī nahāwand twice: first, on two record-sides with Gramophone –the recording we just heard–; and second, an unfortunately lost recording.

Of course, this is another call to our listeners: if someone has Baidaphon’s record including layālī nahāwand on one side and “Uḥibbu layālī al-hajr” on the second side –Baidaphon’s “Uḥibbu layālī al-hajr”, not Gramophone’s–, please contact us and bring us these unfortunately lost treasures. The point of this story is: Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad apparently had a preference for the nahāwand, and sang many dawr, mawwāl and qaṣīda to this maqām. There is a beautiful short qaṣīda: “Uḥibbu layālī al-hajr”… actually, it is only a qaṣīda on the musical level, whereas, on the poetic level, it is only two verses. The lyrics are beautiful “Uḥibbu layālī al-hajr / lā faraḥan bi-hā / ‘asa al-dahru ya’tī ba‘dahā bi-wiṣāl / Wa-akrahu ayyām al-wiṣāli / li-annanī ara kulla shay’in mu‘qaban bi-zawāli”.

He recorded it within his collection of discs to the ‘ushshāq.

Of course, he performed ṣalṭana to the nahāwand ‘ushshāq, and decided to record more of these magnificent tunes.

(♩)

Besides the mawwāl and the qaṣīda mursala, there are two other forms that he neglected to a great extent: the muwashshaḥ –he only recorded two muwashshaḥ “Mā iḥtiyālī yā rifāqī” (ḥijāz aqsāk), and “Imlālī al-aqdāḥa ṣarfan” (bayyātī / samā‘ī thaqīl)…

He did not even record them. For example, he only recorded the first dawr of “Imlālī al-aqdāḥ”… Thank you.

Right. He was only interested in the mawwāl that followed. “Mā iḥtiyālī yā rifāqī” only constitutes a prologue to “Yā albī mālak bi-titnahhid”; “Imlālī al-aqdāḥa ṣarfan” is just an introduction to mawwāl “Eh el-‘amal bi-fu’ādī”. Which implies that Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad belonged to this group of early 20th century Egyptian muṭrib who neglected the muwashshaḥ to a great extent. The only exception was Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī.

True. He recorded many muwashshaḥ in full.

Exactly. He recorded them in full and his interpretation was great. Whereas the pace of Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad’s interpretation of muwashshaḥ is very hasty.

He was more interested in the mawwāl that followed.

Exactly.

Shall we listen to “Imlālī al-aqdāḥ” and the following mawwāl, and kill two birds with one stone? Or to “Mā iḥtiyālī” and the following mawwāl?

Let us listen to “Mā iḥtiyālī yā rifāqī” because it will allow us to compare Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad’s performance to Nādra Amīn’s.

Sitt Nādra? … So shall we will listen to Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad singing “Mā iḥtiyālī yā rifāqī” and the mawwāl following it?

Let us listen to the following mawwāl “Yā albī mālak bi-titnahhid” to the ḥijāz.

Ok.

(♩)

Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad did not record many dawr, which seems strange after we have listened to his interpretation…

Sitt Munīra al-Mahdiyya, for example, did not record many qaṣīda, which is understandable and justifiable: her voice was beautiful, but we must admit that her performance of qaṣīda is not very convincing, as it sounds artificial and does not comply with all the conditions of this art.

Honestly, this also applies to her performance of dawr.

Indeed, Munīra al-Mahdiyya’s only convincing interpretation is her performance of ṭaqṭūqa… and of mawwāl maybe.

Possibly.

Mawwāl or qaṣīda mursala possibly, but surely not qaṣīda ‘ala al-waḥda.

Her performance of qaṣīda mursala is quite good when she imitates Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī.

She imitates him and does not add anything personal.

We would have understood why Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad only recorded very few dawr if his performance of dawr were not convincing. Yet, on the contrary, Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā’s performance of dawr is as good as Salāma Ḥigāzī’s who also recorded very few of those, compared to qaṣīda. Both Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī and Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad were outstanding dawr performers.

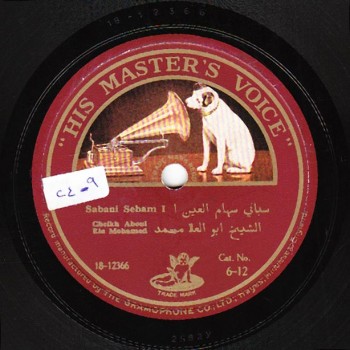

A good example is Al-Maslūb’s simple and primitive dawr “Sabānī sihām el-‘ēn” to the rāst that Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā developed and transformed into a gem.

Let us listen to Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā’s great interpretation of “Sabānī sihām el-‘ēn”.

(♩)

There is also dawr “Ba‘d el-khiṣām ḥibbī iṣṭalaḥ”, of course.

Isn’t this dawr a little controversial?

It is a controversial dawr, because its composer is Muḥammad ‘Uthmān who did not record anything as he lost his voice long before the advent of recording. Many muṭrib recorded dawr “Ba‘d el-khiṣām ḥibbī iṣṭalaḥ” that is composed to the rāst as we well know. Yet, Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad sang it to the nahāwand or…

… the ḥiṣār.

Our listeners will wonder whether the melody is totally different, or if it is a nahāwand version of the same rāst melody composed by Muḥammad ‘Uthmān. What is your opinion?

In the beginning, he started by replacing the rāst with a type of ‘ushshāq then continued to the same maqām…

Doesn’t this remind you of Sāmī al-Shawwā stating that Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā used to ask the instrumentalists to play a dūlāb to a certain maqām…?

He may have wanted to display his talent in metamorphosing a dawr known to be to the rāst into a dawr to the nahāwand, in singing to the nahāwand, adding personal variations, and changing the melody. It is very possible indeed.

Shall we listen to the dawr?

Ok.

It also belongs to the ‘ushshāq collection recorded by Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad in a continuous sequence.

(♩)

Now, let us talk about Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad the composer. Added to qaṣīda, he also composed dawr but in a smaller proportion of course. Again, why didn’t he record many dawr since he composed them?

Not only did Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad compose one or two dawr, he also composed for example ṭaqṭūqa “Illī ‘ishi’ fī īduh ēh”… a beautiful piece, but still only a ṭaqṭūqa. I think the line separating the simple primitive dawr and the “decent” ṭaqṭūqa is quite thin: there is a certain link with the old form of the dawr, i.e. the non-‘Uthmānī dawr (with reference to Muḥammad ‘Uthmān, not to the Ottomans). Dawr “Yā albī ti‘sha’ lēh”, besides being composed by Abū al-‘Ilā, is also a dawr that was performed to an unusual maqām, a maqām musta‘ār derived from the sīkāh but with its own style. It is a beautiful and puzzling dawr. I think Al-Qabbānī and Dāwūd Ḥusnī are those who started to adopt this specific maqām. The following is just an assumption: Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad may have wished to belong to the category of great composers, and to compete with Dāwūd Ḥusnī and Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī by performing a dawr to this rarely used maqām.

(♩)

No one recorded another dawr composed by Abū al-‘Ilā?

To my knowledge, the melodies composed by Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad and performed by other artists than himself were all qaṣīda. I do not think anyone recorded a piece, a dawr for example, by Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad.

We have reached the end of today’s episode and the end of our discussion about Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad.

We thank Prof. Frédéric Lagrange and we will meet again in a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

“Min al-Tārīkh” is brought to you by Mustafa Said.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)