The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

In today’s episode, we will resume our discussion about the History of Recording in the Arabian Gulf with Mr. Kamal Kassar and Mr. Ahmad al-Salihi.

We ended our previous episode talking about the recording phenomenon that went beyond Kuwait and spread out to the whole Arabian Gulf region.

Zuwayyid’s recordings triggered the expansion of music in the Arabian Gulf: the first two or three years, it was limited to Kuwaiti musical culture, whereas in 1929, it spread out and included the Bahraini culture. They are said to be different cultures, but in fact their pillars are the same while their application is different. The appellations and the types of singing are similar.

Later on, the 1930’s witnessed the first recordings of numerous muṭrib such as Bahraini Muḥammad Fāris who had refused to record at first. It is said that he asked Zuwayyid to record with Baidaphon in order to find out if the microphone would steal his soul. He was reassured and recorded in 1932 with His Master’s Voice.

Where?

In Baghdad. He was accompanied by Dāḥī Bin Wulayd who in 1920 was working at sea as a nahhām, i.e. a divers’ muṭrib.

In Basra –they used to travel from Bahrain to Kuwait and back– they met with mirwās player and percussionist Su‘ūd al-Makhāyṭa who also sang and agreed with the representative to record a collection of ṣawt and to sing. So he went with them from Basra to Baghdad.

They already had a Kuwaiti percussionist residing in Bahrain named Ḥamad Abū Ṭaybān Abū Huwaydī –Huwaydī is a diminutive of ‘Abd al-Hādī, the name of his eldest son. So, Muḥammad Fāris went with them, and the group now included two Bahrainis and two Kuwaitis.

In Baghdad, they had violinist Ṣāliḥ al-Kuwaytī who lived there and was an expert at these local fann.

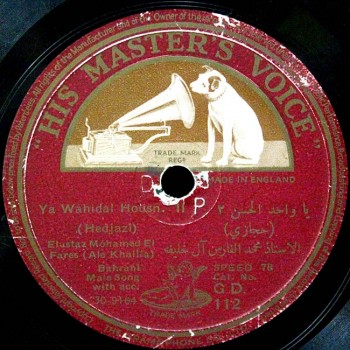

His Master’s Voice recorded a large collection including: Muḥammad Fāris who only recorded ṣawt; Dāḥī Bin Wulayd who only recorded ṣawt except for one record dedicated to women wedding songs called ‘āshūrī in Bahrain, and radḥa in Kuwait; and Su‘ūd al-Makhāyṭa who recorded a collection of ṣawt, khammārī and fann that is among the most famous recordings to-date in Kuwait as well as one of the most famous and most beautiful recordings of the Gulf repertoire.

What will you play for us from these recordings?

We will listen to Muḥammad Fāris singing ṣawt “Yā wāḥid al-ḥusn”.

(♩)

Mr. Mubārak al-‘Ammārī said that during a studio break in Bahrain, Dāḥī Bin Wulayd sang along with Muḥammad Fāris a wedding song known throughout the Gulf countries.

What does it say?

“Sālim yā Sālim, āh yā Salmān”… According to some historical sources, it was written by an old muṭriba for her son who married and then died… the mother talking to her son through the lyrics. It is also said that the son wished to marry a girl but that it did not work out, and so the mother who was a muṭriba sang this song at the girl’s wedding, referring to her son who could not marry this girl.

The point is that either the studio’s manager or another person that was present there heard it and liked the light and fast melody –all wedding songs are known to be light and fast. He asked Muḥammad Fāris to record it, but the latter refused saying: “I am a man and I only sing ṣawt” –which he truly did. So he asked Dāḥī who agreed to record this fann and did. But it seems that the latter did not know the lyrics and forced Muḥammad Fāris to take over. We will notice that the second record-side, the last quarter of the record, is performed by another muṭrib singing “Yā Dāna Dāna”… It is a beautiful and light song.

(♩)

During the 1930’s, all the record companies whether international or national, recorded abroad, such as SODWA in Aleppo, N‘ayyim in Baghdad, and of course Baidaphon in Baghdad.

When did SODWA record in Kuwait?

SODWA recorded at different periods: Muḥammad Fāris in 1936, Dāḥī Bin Wulayd in 1935, and apparently Bahraini Muḥammad Suwayd –this is only hearsay, I never heard his record–; and ‘Abd al-Laṭīf al-Kuwaytī in 1938.

SODWA’s recordings were all made in Aleppo, and they all included Syrian or Lebanese violinist Ilyās Fannūn who was famous at the time and is among those who participated in the 1932 Music Congress. He accompanied Muḥammad Fāris, Dāḥī Bin Wulayd and ‘Abd al-Laṭīf al-Kuwaytī.

Muḥammad Fāris and Dāḥī were both ‘ūdists who played and sang, while ‘Abd al-Laṭīf al-Kuwaytī was not a ‘ūdist. So famous Syrian ‘ūdist Nūrī al-Mallāḥ was brought in to accompany him, as well as a riqq player who tutored ‘Abd al-Laṭīf al-Kuwaytī as to Kuwaiti rhythms… and he recorded a collection of discs.

Muḥammad Fāris was accompanied by Bahraini percussionist Jawhar al-Najdī, and Dāḥī was accompanied by another percussionist called Bilāl.

These recordings were very successful, especially those of Muḥammad Fāris that included less-known tunes such as “Allāh yā rabbāh” and “Yā man bi-sahmih ranā”. Dāḥī presented a collection exclusively dedicated to beautiful ṣawt, and Muḥammad Fāris only sang ṣawt as I mentioned earlier. ‘Abd al-Laṭīf performed a more varied repertoire, including a madīḥ (praise) to Aḥmad al-Jābir and to ‘Abd al-‘Azīz Āl Su‘ūd, the King of Saudi Arabia at the time and its founder. He also sang sāmirī “Yā wannitī wannat ‘alīl yudāwūnah”, one of the most famous discs ever known in the region.

Can we listen to it?

Yes.

(♩)

The local national companies first appeared in the late 1940’s after the World War, and the first founder of a local record company was His Master’s Voice’s representative ‘Abd al-Ḥusayn al-Sā‘ātī. He decided to establish a record company in Bahrain and bought a recording machine from London through a newspaper ad. It reached Bahrain and he started recording.

What is the name of the record company?

It is actually a group of names for a group of companies owned by brothers who had a disagreement. Each took a different label.

But let us talk about an important issue: right after the World War, Kuwaitis and Bahrainis went to Bombay in India, and recorded under national names such as “Kuwait-phone”, “Layla-phone” or “Sālim-phone” (Sālim being the name of the producer or the muṭrib). They recorded in Bombay’s Gramophone studio under local names. The studio was large and there was a record-printing factory. This industry was very strong in India. People from the Gulf mainly recorded with Odeon and His Master’s Voice in Bombay, but later on some local producers decided to record under their name, such as Basra-phone owned by an Iraqi producer who recorded Kuwaiti muṭrib in India.

Still, we are only talking about local names, not about record production in the Gulf.

The first Gulf record production happened with ‘Abd al-Ḥusayn al-Sā‘ātī and his brothers, and I think the name of the company was “Arab Discs” that had a simple blue label. They recorded a very large number of muṭrib: any muṭrib who played ‘ūd recorded a disc. In this period, i.e. the late 1940’s, Bahraini song masters had passed away: Muḥammad Fāris in 1947 and Dāḥī in 1941. The only one left was Muḥammad Zuwayyid who recorded a large collection. There were also Kuwaitis who went to Bahrain and made recordings… it had become very easy. Kuwaiti ‘Abd Allāh Faḍāla for example, a muṭrib at the Bahrain Radio, recorded a collection of discs in Bahrain; Ḥamad Khalīfa, the only muṭrib from this era who is still alive, recorded his first collection in Bahrain in the early 1950’s.

Many recording companies were established, some of them excellent, and they printed their records in London and in Bombay. The quality was excellent. Those included Ibrāhīm-phone and his brother Kurjī-phone, as well as many other names such as Bahrain-phone of course and Kuwait-phone among many others.

Since we are discussing discs… you know that the waṣla in Egypt and Syria only appeared dismantled on the discs: one could listen to the dawr, the mawwāl, the muwashshaḥ, and the qaṣīda separately, but never together because their duration exceeded the capacity of the records. Can we talk about this issue regarding Kuwaiti and Bahraini recordings?

Of course. The capacity of a disc could fit one song at most, or two in some rare cases, one song on each side. This is why it was impossible for a whole waṣla, or faṣl as we call it, to be recorded in full on one disc.

Also, and this is an issue we may discuss later, the structure of the faṣl itself changed with the advent of recording. Today, fann still exist and are well performed. But the structure of the faṣl has changed since the 1920’s: today, we practice it differently from the 1920’s.

So they recorded some forms on the discs, often separately, the same as in Egypt: each song on a separate disc. And these discs will not show whether a certain song is in the beginning, the middle or the end of the jalsa, or why, and on what basis they can be distinguished one from the other. There are no explanations based on the local culture that can enlighten listeners.

Later on in the 1930’s, they opted for more commercial singing, like the ṣawt that was the most requested by the listeners, followed by the other fann. Note that the recording of some fann stopped from the 1920’s until the Radio stage: they appeared a little then disappeared, and reappeared again later in the 1950’s Radio recordings. This issue may necessitate a full episode.

Then the complete faṣl was only Radio-recorded and TV-recorded…

No. It was never Radio-recorded or TV-recorded. It was always dismantled.

Always dismantled.

Always. Commercially speaking, if I wanted to listen to a faṣl, I would need to listen to the istimā‘, the ṣawt ‘arabī, the ṣawt shāmī, the ṣawt khayālī, and the khitām… five songs that require half an hour. Yet they were not recorded in this fashion. The faṣl continued to be performed in full by the artists, in jalsāt and in dawr, but it was always dismantled in the recordings.

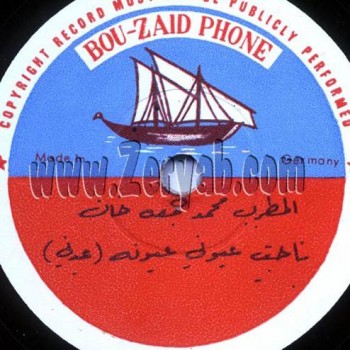

The first Kuwaiti record company, Ṭah-phone, was established by Kuwaiti Ṭah Ṣabrī. He first recorded ‘Abd Allāh Faḍāla and Ḥamad Khalīfa in Bahrain where Ḥamad Khalīfa met with Bahraini and Omani muṭrib who were recording, as he later told me. Later on in Kuwait, Ṭah Ṣabrī established a record company and brought a machine to record the performances of the Kuwaiti and Bahraini muṭrib, starting off the recording industry in Kuwait, followed by Abū Zayd-phone.

When was Ṭah-phone established?

In the early 1950’s, in 1952 I think. It was followed by Abū Zayd-phone, a very successful record company that continued to make records until the 1960’s and went on selling them through the 1990’s. This company made recordings of numerous muṭrib, including local ones, Yemeni Muḥammad Jum‘a Khān, as well as Bahraini and Iraqi muṭrib.

Are there any available archives?

There are a lot, but of course some are missing, as always.

We could listen for example to a Yemeni song performed by muṭrib Muḥammad Jum‘a Khān, recorded in Kuwait by Kuwaiti record company Abū Zayd-phone.

(♩)

Dear listeners, we have reached the end of today’s episode.

We will meet again in a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

“Min al-Tārīkh” was brought to you by Mustafa Said.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)