The ṣabā maqām is ranked as the seventh key and the fourth derived maqām, born from the dūkāh and the ḥijāz.

The ṣabā maqām is ranked as the seventh key and the fourth derived maqām, born from the dūkāh and the ḥijāz.

Its original appellation is said to be ṣabāḥ –as spelled in Turkish–, but Turanians pronounced it ṣabāh because they could not pronounce the ḥ, and thus it reached the Arabs as ṣabā and was written as such in the 20th century theoreticians’ books. Only a few Sheikhs pronounced it ṣabāḥ.

Also, Ṣafiyy al-Dīn al-Armawī used a melodic pattern resembling the ṣabā, called kawāsht.

The scale of the ṣabā maqām is as follows: dūkāh, sīkāh, jahārkāh, ṣabā, ḥusaynī, ‘ajam, kardān, and muḥayyar (the dūkāh’s jawāb).

The muḥayyar is often altered with the shahnāz, because the maqām’s pattern adopts the ḥijāz aspect at its third. As a result of this alteration, its scale seems incomplete.

Mustafa Said says about the ṣabā maqām:

The ṣabā maqām is of a “gripped feeling” nature. Unlike some, I do not think that “gripped feeling” necessarily implies sadness.

Here are some examples illustrating my point of view:

a significant number of old ṭaqṭūqa performed by ‘ālima are to the ṣabā;

the joyful layālī of Aḥmad ‘Adawiyya, may God grant him good health, are also to the ṣabā.

The Fajr (dawn) prayer, the ṣubḥ (morning) prayer, was called to the ṣabā, which is why I am more convinced with the Turkish spelling ṣabāḥ –pronounced ṣabāh by the Turks, with an h instead of the ḥ because Turanians can’t pronounce the ḥ. This is just my opinion… the word might as well be related to the ṣabā wind or to anything else.

The “gripped feeling” nature of the ṣabā is a result:

of the falling fourth… (♩);

as well as of the parallel intervals between the second, the third, and the fourth… (♩)… that are very close: approximately a ¾-tone, with just minor differences, because they can’t be equal as adjusted tuning does not exist in Arab music.

The ṣabā was either formed independently, or resulted from the meeting of the bayyātī and the ḥijāz, or even the sīkāh… (♩) … like the bayyātī…

If I continued, I would be playing to the ḥijāz… (♩)

All this shapes the ṣabā aspect… (♩)

The ṣabā’s fourth is not the same as the ḥijāz’s third… (♩)

There is a difference of up to a third-tone.

To some, the ṣabā scale is incomplete since, when the ḥijāz’s aspect is complete, its dīwān is one semitone shorter, as illustrated by the audio sample… (♩).

Still, whether the dīwān is complete or not… (♩), the maqām remains the ṣabā.

The dīwān is incomplete because of its third resembling the ḥijāz aspect. When tuning my (‘ūd) to the ṣabā, I tune its third and not its fourth (both qarār to the minor third, a dūkāh qarār and a jahārkāh qarār)… (♩).

While, when playing to the bayyātī or to the ḥijāz, I tune the fourth (dūkāh and yakāh qarār, exposing the partially fixed position on the ṣabā’s third)…

(♩)

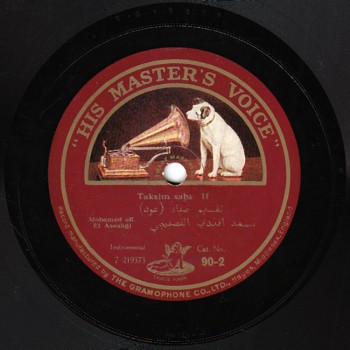

Let us first listen to a ‘ūd taqsīm to the ṣabā played by Muḥammad al-Qaṣṣabjī, recorded by His Master’s Voice –daughter company of Gramophone– on one side of a 25cm record, # 7-219373, matrix # BF 1200.

(♩)

Muwashshaḥ to the ṣabā include “Ghuḍḍī jufūnaki” composed to a 19-pulse’ rhythm. Let us listen to it performed by Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī, recorded around 1909 by Baidaphon on two sides of a 27cm record, # 1322 and 1323. Side 2 includes a taqsīm layālī and mawwāl “Lā taḥsibū inn al-bi‘ād”, accompanied by Ibrāhīm Sahlūn (kamān), ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī (qānūn), and ‘Alī Ṣāliḥ (nāy).

(♩)

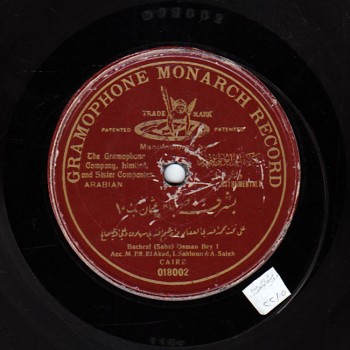

Let us listen to ‘Uthmān Bēh’s bashraf ṣabā –one of the many instrumental pieces composed to the ṣabā maqām– played by the takht of Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād (qānūn), Ibrāhīm Sahlūn (kamān), ‘Alī ‘Abduh Ṣāliḥ (nāy), and Muḥammad Abū Kāmil al-raqqāq (percussions), recorded in 1908 by Gramophone on two sides of a 30cm record, order # 018002 and 018003, matrix # 119 P and 120 P.

(♩)

The ṣabā maqām is among those with the least sub-maqām, and is the most compound maqām of the main maqām, as described earlier. The ṣabā’s sub-maqām include those shared with another key, such as the bastanikār said by some to be a sīkāh sub-maqām in relation to its fundamental position, while others say it is a ṣabā sub-maqām in relation to the pattern. Both are right. The same applies to the Turkish jahārkāh said by some to be a ḥijāz sub-maqām in relation to the aspect’s fundamental position, and by others to be a jahārkāh sub-maqām in relation to the key’s fundamental position, while others say it is a ṣabā sub-maqām in relation to the pattern. The same applies to the shawq namā.

The ṣabā’s sub-maqām include the ṣabā būslīk, ṣabā shāwīsh, ṣabā zamzam, the kawāsht, etc.

Let us now listen to qaṣīda mursala “Anā ḥirmānu nāẓirī” to the Turkish jahārkāh by Yūsuf ‘Aramūnī whose performance resembles Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s style in chanting qaṣīda, recorded around 1912 by Baidaphon on two sides of a 27cm record, # 30506 and 30507.

(♩)

The ṣabā is among the keys that are easy to shift from smoothly to neighbouring notes as well as to farther notes.

Let us now listen to qaṣīda mursala “Ahlan bi-ghazālin” and tawshīḥ “Bi-ṣafā al-ījāb” both performed by Sheikh Maḥmūd, and both including predominating melodic shifts to ṣabā sub-maqām as well as to neighbouring maqām such as the ‘ajam, recorded around 1926 by Odeon on one side of a 27cm record, order # X 55607, matrix # XE 3126.

(♩)

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Niẓāmunā al-Mūsīqī”.

We will meet again in a new episode.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)