The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Today, we will discuss music in Yemen –“Al-Yaman al-Sa‘īd” (“Happy Yemen”)– with Prof. Jean Lambert, a music researcher specializing in Music in Yemen. Prof. Lambert has numerous publications on this subject and collaborated to an audio publication on this art. He will tell us about these subjects in today’s episode and possibly in other episodes on this same subject.

Good morning Mr. Jean.

Good morning.

Your presence in today’s episode as well as in the coming episodes honours us.

The honour is all mine.

This show attempts to shed a light on quasi-forgotten musical types, such as the music in Yemen, unfortunately unknown outside the region and quasi-forgotten in Yemen itself. Do you agree?

Everybody, anywhere in the world, forgets.

Yemeni music in general, with its different types, is not famous in the Arab countries, except for the Arab Gulf where it is mostly known on the commercial level, not as a heritage.

Yemen, as a country, remained isolated for a long time, mainly during the first half of the 20th century when the fundamentalist political-religious system in Sanaa isolated it and did not encourage art in general and music in particular. Upon the 1962 revolution, Yemen opened up to the rest of the world, but it was poor and unable to spread its heritage outside its historic borders.

Before we go further back in time, let us listen to a piece to introduce this art. Most of our listeners today surely do not know much about it. What would you like us to play first?

Let us listen to a Sanaa song titled “Yābī rōḥī min el-ghēb” sung by Mr. Ḥasan al-‘Ajamī recorded on a CD at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris.

(♩)

Now that we got a glimpse of this music, let us go back as much as possible to the beginning. In your opinion, where did this Yemeni music originate from?

Music in Yemen has existed for a very long time. And, the same as with all other peoples, there are stone drawings… those in Yemen go back to the 8th and the 9th centuries B.C., and represent artists playing the lyre or the samsamiyya and playing drums during the Kingdom of Ṣaba and the Kingdom of Ḥimyār… a very ancient past indeed.

Music in Yemen evolved a lot with time and throughout the different civilisations. The beginning of Islam in Yemen and the cultural movement started in the north of the island undoubtedly brought new musical instruments, types, and forms. The ‘ūd, for example, was apparently not used in Yemen before Islam, yet there are indications of its existence there after Islam.

… Added to the vocal forms such as the Sanaa singing including ḥumaynī poetry –classical poetry influenced by the local colloquial language– that has existed in Yemen since the Medieval period (Middle-Ages), i.e. at least since the 12th century or the 13th century.

During the Ayyubid dynasty?

During or after the Ayyubid dynasty.

So, the instruments played before Islam are the ones drawn, i.e. the lyre and the samsamiyya? And the ‘ūd reached Yemen but, surprisingly, kept its pre-Abbasid appearance, i.e. with the animal skin cover.

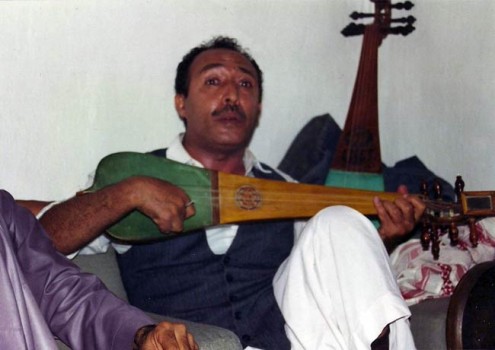

Indeed, the ‘ūd used in Yemen until the beginning of the 20th century was strangely not the ‘ūd kumaythrī known in the Arab culture since the drawings of Al-Ḥarīrī’s maqāmāt, or even the drawings of the Alhambra showing the ‘ūd with a more or less large wooden cover, while the Yemeni ‘ūd called ṭarab in Sanaa has a unique body covered with goatskin or sheepskin that produces a distinctive sound –maybe softer– that is difficult to describe, yet undeniably distinctive. It is thinner and small, and thus can be played standing up, which is very practical to accompany dancing.

So, the small ‘ūd is the closest to the ‘ūd described by Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ṭaḥḥān in “Ḥāwī al-funūn wa-salwat al-maḥzūn”.

With all due respect, I think that Ibn al-Ṭaḥḥān described a big ‘ūd kumaythrī because he mentions the subject of the paintings for example.

But he says that the ‘ūd before it had an animal skin cover.

Indeed.

He mentioned the ‘ūd that existed before his era, described it as having an animal skin cover, and gave a detailed description of the contemporary ‘ūd with a wooden cover. Still, before that, he talked about the ‘ūd with the animal skin cover.

Indeed. And he may have called this ‘ūd “barbaṭ”.

Before Ḥasan al-Ṭaḥḥān’s writings, there were descriptions that unfortunately lacked precision, in “Kitāb al-Aghānī” for example.

Indeed. Other descriptions, including one description whose author I forgot, describe the barbaṭ with the cover made from soft animal skin and the neck …etc.

The appellation barbaṭ is derived from Persian and from Arabic: “bar” means chest in Persian, and “baṭ” means duck in Arabic. Indeed, the shape of this ‘ūd from head to body resembles the shape of a duck’s chest.

Thus, the ‘ūd that reached the Arabian Peninsula and the Ḥijāz coming from Persia during the early Islamic era and the Umayyad era is the same that reached Yemen, settled there, and kept its shape with all the changes that affected the ‘ūd later on in the Arab Levant.

Yes. This is one possible explanation. We actually do not know when it reached Yemen, yet there are indications that it existed there in the 13th century along with the ‘ūd kumaythrī. So, both ‘ūd co-existed in the same place during the same periods, in Yemen but also in other regions of the Arab World, such as Andalusia and Morocco where it still exists under a different shape, the rabāba played with a bow, whose shape is very similar to the ṭarab instrument, also called qanbūs in Yemen, an appellation probably derived from Turkish, since in the History of Turkish Music there is an instrument called kūbūz that probably was Arabized into qabūs then qanbūs.

Let us go back to the medieval period.

Yemen, during and after the Ayyubid Dynasty, witnessed the rule of the Rasulid dynasty.

The descendants of the Ayyubid?

Yes. They did not draw but wrote many books on the economic, social, and agricultural life, including a report on the city of Ta‘z’ markets and factories, published in Sanaa ten years ago by the Centre français d’archéologie et de sciences sociales, with a beautiful mention about the manufacture of the ‘ūd kumaythrī and the Yemeni ‘ūd with the animal skin cover.

It seems that music boomed during the Rasulid dynasty. Can we talk about this?

Indeed. The Rasulid dynasty had an elite of the Ayyubid army who worked hard to bring into Yemen elements of civilisation, including crafts, techniques of agriculture and irrigation, as well as the administration of the dynasty.

As for music, musician ‘Abd al-Lāh al-Fārisī who came from Iran wrote two books about music theories. They were unfortunately lost, but were mentioned in the 13th century in Yemen. Furthermore, the Rasulid kings were keen on practising Sufism… Religious chanting was practised under the Sufi Sheikhs, including famous Sheikhs who followed the way of Ibn ‘Arabī.

With Sufi inshād and the Rasulid dynasty, we reach the end of today’s episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

We will meet again in a new episode to resume our discussion on Music in “Al-Yaman al-Sa‘īd”.

We thank Prof. Jean Lambert for the valuable information as well as for the precious recordings from his private collection that he shared with us.

“Durūb al-Nagham”.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)