The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Today, we will resume our discussion about Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī with Prof. Frédéric Lagrange.

Let us discuss the “trustworthy muṭrib” issue that primarily concerns the dawr and implies that the muṭrib performs the dawr exactly as it was composed, i.e. the performance is a perfect reflection of the composer’s intention… whether or not this composer recorded the melody himself and had a beautiful melodious voice like al-Qabbānī –by the way, al-Qabbānī’s voice was quite good– or like Dāwūd Ḥusnī’s voice that was less “charming” and beautiful than al-Qabbānī’s while he remained, nevertheless, a great performer… We will discuss this further.

The issue concerning the interpretation of the dawr with a faithfulness that complies with the intention of the composer –who supervises the performance/interpretation and goes through it again with the performer– bears an important significance, notably starting 1910-11, i.e. after the first decade of the 20th century, with the advent of copyrights to artistic works, when dawr were recorded commercially and were the property of a record company.

The composers we are referring to are limited to Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī, Dāwūd Ḥusnī, Sayyid Darwīsh, and maybe Zakariyyā Aḥmad in the last stage.

Are there any other masters besides them who composed major dawr in the early 20th century? Can you name any who made commercial recordings with record companies?

Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī and Dāwūd Ḥusnī recorded with Gramophone, and Sayyid Darwīsh and Zakariyyā Aḥmad recorded with Baidaphon.

Exactly, they are the only ones.

So, a composer searching for a muṭrib who would perform the dawr exactly as he composed it was an existing concept at the time.

While the concept of trustworthy/faithful performance of dawr in ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī and Muḥammad ‘Uthmān’s generation, even the interpretation of al-Qabbānī and Dāwūd Ḥusnī’s compositions before 1910, is meaningless because a muṭrib’s value/quality was measured proportionally to his ability to create and to interpret what he invented during his performance. Consequently, the nickname “trustworthy muṭrib” –when appropriate– probably indicates the preference of Dāwūd Ḥusnī and Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī for al-Ṣaftī compared to others because they thought he was, to a certain extent, “guaranteed”: they were confident their compositions would be interpreted to their satisfaction.

In my opinion, the same applies to Zakī Murād, particularly concerning the dawr recorded by Gramophone, composed by either Dāwūd Ḥusnī or Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī, and interpreted with equal competence by Sayyid al-Ṣaftī and by Zakī Murād.

They were both undoubtedly as competent and as trustworthy/faithful, and they are the only two who recorded dawr.

On the other hand, “trustworthy muṭrib” does not apply to Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy –who was then a young man at the beginning of his artistic journey– whose powerful voice was not chosen by the record companies during this period to perform this musical piece. Actually, there is a pleasant story about Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy riding a carriage, with Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb running after him, and with the coachman hitting Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb with his whip… A story that is untrue and whose sole purpose, in my opinion, is to convey the impression that Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb and Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy were from different generations, Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb representing the young and Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy representing the old one. I do not think there was more than a 10 years’ difference and surely not a full generation difference between Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy and Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb.

This story is not accurate.

Indeed, because it has an ideological purpose aiming at separating a generation from another.

Let us go back to our initial question: why wasn’t Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy chosen? Why wasn’t he considered a “trustworthy muṭrib”?

Maybe because he had not started to record dawr in 1918-1919, as he was still young then…

Yet, after that, Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy specialized exclusively in the repertoire of ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī and Muḥammad ‘Uthmān, and in the old dawr of the late 19th century and those of 1902-3-4, i.e. the early dawr by Ḥusnī and al-Qabbānī… yet mainly those by Muḥammad ‘Uthmān and ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī.

While the pieces he sang that were composed by the other two were ṭaqṭūqa rather than dawr.

Exactly.

So the composers surely noted the difference between Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy’s performance policy and that of Zakī Murād and Sayyid al-Ṣaftī who belonged to the same boot camp, while Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy belonged to another boot camp. Don’t you think?

I agree. Listening to dawr “Ḍayya‘t musta’bal ḥayātī” –that we do not have the time to listen to today– interpreted by Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy and its relation to Sayyid Darwīsh’s interpretation, and dawr “Anā ‘ishi’t” by Sayyid al-Ṣaftī and it relation to Sayyid Darwīsh’s version, clearly shows that they belonged to two totally different boot camps.

Which dawr shall we listen to? I suggest we start, if possible, with Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s very old recordings made in 1903. Are there any?

There is a copy of dawr “El-bulbul gānī” composed by al-Qabbānī, and that was quite widespread at the time…

And among al-Qabbānī’s major dawr.

Let us listen to it.

(♩)

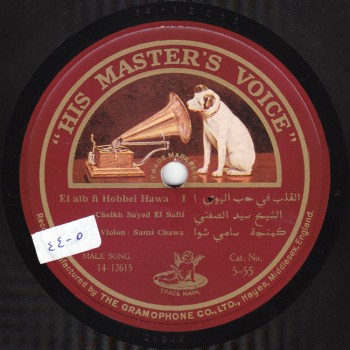

What about “El-alb fī ḥukm el-hawa” to the ḥijāzkār kurd?

There is a big problematic concerning the ḥijāzkār kurd in this dawr.

Is there a difference between the ḥijāzkār kurd and the kurd? You are the maqām expert…

Its composer dealt with the ḥijāzkār kurd as if he were dealing with a ḥijāzkār then modulated to the kurd. He started as if to the origin of the maqām ḥijāz then concluded to the kurd or rather to something closer to the bayyātī than to the kurd. The pattern is different from the ḥijāzkār kurd’s. The result of the composer’s “vision” is a maqām with a new, beautiful, and melodious pattern. Furthermore, even though the modulations in the dawr are surprising, and maybe somewhat abrupt if dealt with clumsily, yet Sayyid al-Ṣaftī turned this abruptness into infinite smoothness.

What abruptness are you referring to concerning this dawr?

I am talking about the sudden change of the original maqām from ḥijāz to kurd. Sometimes, it is more surprising than it should be. But the smoothness of Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s vocal performance turned this sudden surprise into a smooth modulation.

(♩)

Dear listeners,

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Min al-Tārīkh” dedicated to Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī.

We thank Prof. Frédéric Lagrange.

We will meet again in a new episode to resume our discussion about Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī.

“Min al-Tārīkh” is brought to you by Mustafa Said.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)