The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

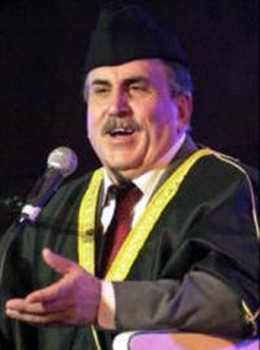

Today’s episode is exceptional: we will be discussing the Iraqi maqām with a legend of the Iraqi maqām, Mr. Ḥusayn al-A‘ẓamī.

In Iraq, the appellation maqām does not indicate the same thing it does in the rest of the Arab Mashriq: it is neither the melodic scale, nor the pattern during the performance, nor the Arab Maghrib’s ṭab‘. Our closest –but not perfect– “equivalent” of the Iraqi maqām is the maqām waṣla. Am I right or wrong, Mr. Ḥusayn?

You are right.

Shall we start with a precise definition of the Iraqi maqām, or maqām in Iraq?

Thank you for this introduction, Mr. Mustafa. I hope I deserve it.

You more than deserve it.

May God protect you. Thank you very much.

In my numerous writings that were also published in my books, I talked about the Iraqi maqām, its nature, and its definition, and added the definitions presented by others, including critics and writers. I realised that one definition is never enough to get to know anything: there are social, artistic, or scientific definitions… depending on the concerned field of specialization. Thus, one definition is not sufficient to explain any subject, especially singing that is a sensory –not a material– subject requiring precise words, definition, presentation, etc. Yet, I presented all these different definitions in relation to the subjects of the book, including the functional, the social, and the scientific.

Here are some of the definitions I presented in my first book “Al-maqām al-‘irāqī, ila ayn?” published in 2000 or 2001:

- The Iraqi maqām is a specific type within the precise system of the strong principles of performance, a sensory work whose combined components create a whole and unified structure.

- The Iraqi maqām is a typical Iraqi heritage “instru-vocal” work that depicts, through comprehensive multi-facet’ –performance forms and components– images, life in Iraq including its history, civilization, culture, and aspects, reflects the identity and personality of its people through a social approach, and illustrates the evolution of life in this noble country including its interactions throughout the long and complicated circle of life extended over thousands of years of History.

- The Iraqi maqām is an ensemble of musical notes whose structures are often close and sometimes different.

- The Iraqi maqām, in its most recent definition, is a historic classical instru-vocal artistic form whose structure and components are specific to Iraq, as compared to other provinces in Western and Central Asia, and the Arab World. Its deep nature is Iraqi Arab while its influences are Asian –its expressive aspect definitely bearing West Asian influences–. We will learn about the influences that affected its form and appellations, among others, through the upcoming questions.

Before we tackle the Iraqi maqām in detail…

I have come across some preparatory documents related to the 1932 Cairo Congress of Arab Music and that refer to the maqām irāqī as the maqām baghdādī. Would you please develop this point?

Explaining these two appellations, “maqām irāqī” and “maqām baghdādī”, would take too long, and would require a full lecture or a whole book.

Let us start with the appellation “maqām irāqī”:

Historically, Iraqi maqām and Iraqi singing are considered to be recent, three or four centuries old. The term maqām and the expressions related to its performance already existed, but they took shape and evolved throughout the years, and incorporated many cultures, numerous cultural, political, economic, social, and artistic phases/periods, gradually taking shape until a form was born. These performances were codified with the passing of time, their dimensions becoming clearer, including a beginning, a core/trunk, and an end, that all shaped the form of the Iraqi maqām whose structure from then on was made of five essential elements present in each maqām. This vocal form was named Iraqi maqām.

It was named “maqām irāqī” because:

- Not all the Governorates in Iraq sing the Iraqi maqām. Then why was it named Iraqi maqām? Knowing that the maqām reached Baghdad, took shape and was codified there, reaching a structure, clear dimensions, elements, and pillars/basis, and knowing that Baghdad is the capital of Iraq and that all capitals represent their country, the maqām was named maqām irāqī and not maqām baghdādī.

- Naming a maqām “maqām irāqī” implies the existence of non-Iraqi maqām particularly in Western Asia, including the Iranian maqām, the Turkish maqām, and the Azerbaijani maqām… These are provincial issues. Thus, it might have been from this perspective that it was named “maqām irāqī” to differentiate if from the other provinces or regions that deal with maqām.

To me, there is no big difference between the maqām in Azerbaijan, the Iranian dastkāh, the Iraqi maqām, the Turkish fāṣil, the oriental waṣla, and the ṭab‘… I think that the language difference between the provinces of one nation, such as the language difference between Egypt and Iraq…etc., is the same as the difference between the Iraqi maqām and the musical waṣla. I do not understand this strange separation between the region’s petty states.

Anyway, let us start talking about…

…the “Baghdadi maqām”:

Concerning the maqām baghdādī, in Iraq, in the Governorates that sing maqām –the first chapter of my second book “Al-maqām al-‘irāqī bi-aṣwāt al-nisā’ ” dedicated to women’s attempts at singing Iraqi maqām throughout the 20th century, is an elaborate study with personal opinions that are either accepted or opposed until today, and criticized by many critics. The ideas I presented in this book truly reflect my feelings and my convictions. The most debated opinion concerns the origin of maqām being a mountain environment. The question was how they reached Baghdad, a flat land. Iraqi maqām in North Iraq’s mountainous Governorates –today, the province of Iraqi Kurdistan– are seen as the homeland of these maqām performances, extending to the vast geography of Western Asia where most or all the states enjoy such mountainous environment. Thus, we wonder how these maqām reached Baghdad, a flat land, while affirming that maqām were born in the mountains. If Baghdad were not a capital… even during the period of decline, and of occupation, the period called the dark ages by historians, i.e. seven centuries exactly from the fall of the Abbasid Caliphate (656 Hijri, 1258 A.D.) to Iraq’s independence (1958 A.D.) when Iraq suffered domination and invasions, and witnessed social and cultural blending. So, during these dark ages, Iraq was under a great many influences brought on by Hulagu the Tatar, the Jalairid, the Ak Koyunlu (State of the While Sheep Turkomans), the Mongols, the Kara Koyunlu (State of the Black Sheep Turkomans), Timur, Uzun Hasan, the Safavid Dynasty, and finally the Ottomans who stayed for approximately 400 years, the Ottoman civilization being the longest one Iraq experienced before WW1 as they governed the Arabs for 4 centuries after the fall of the Abbasid Dynasty.

And finally the British.

The maqām reached Baghdad during this time of influences, this period of decline and backwardness, and Iraq was governed from Baghdad that is located at its centre. Another proof is that the Governorates of the centre of Iraq –Al-Ḥilla, Al-Kūt, Karbala, Najaf– surrounding Baghdad did not have maqām. The only city at the centre of Iraq that dealt with maqām was Baghdad.

First, Baghdad is a city, i.e. a new environment for maqām known to have originated in the mountains.

Second, Baghdad being unlike any other city of Iraq since it is the capital, and thus houses the State Centre, universities, State Departments, philosophy and intellect, these influences were codified there, they were not wasted. This was the beneficial impact of Baghdad on maqām. Even as a true Baghdadi Iraqi Arab, I must admit the scientific truth that Baghdad is not a geographical centre of maqām. These influences reached it through the governmental centres, the invasions…etc., and the maqām took shape during the dark ages and became a form with well-defined dimensions, with a beginning, a core/trunk, and an end, including fixed elements in every maqām.

Another subject must be discussed here, but I will not introduce it now as it might be introduced by your questions, Mr. Mustafa.

Let us discuss how Baghdad was beneficial to maqām that now originated in a city, not in the mountains.

Yes… Codifying the construction of the maqām or transforming popular folklore into literary music, if I may translate “classique” into literary…

I only disagree with you concerning the historical aspect and describing these seven hundred years as the “dark ages”… I do not agree with what the orientalists taught us. Anyhow, this difference in opinion does not harm our debate. In Iraq, the construction of the Iraqi maqām evolved during the Ottoman era, which proves that this period was not a “dark age” for music.

The appellation “dark ages” does not concern music only, it concerns life in general, the scientific aspect, the social aspect… all the aspects in the life of Iraqis, especially in Iraq, but also throughout the Arab World yet differently. Though it was the darkest in Iraq that was closer to the Turkish border. Historians and Orientalists are entitled to name it the “dark ages” because what happened during these seven hundred years, or seven centuries, is truly surprisingly painful…

(♩)

Let us go back to the maqām irāqī following the chronology, starting from its birth in the mountains to the codified classical literary artistic form that we heard in the early 20th century recordings. How did this non-codified folkloric popular mountain form reach its contemporary form?

Baghdad is the capital of Iraq as well as the Governance Centre since it was established, and thus the intellectual centre as well as the centre of state departments, universities, and of everything… Many aspects of life were codified there.

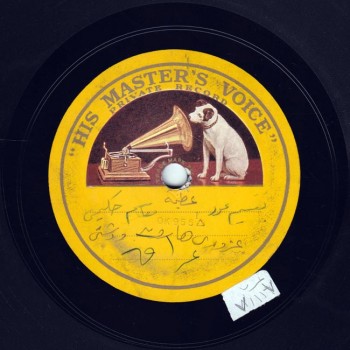

Now let us focus on music: all the elements related to heritage music were codified. In the 19th century, the Iraqi maqām reached the peak of classicism, the peak of its maturity and its completed final form/shape/structure. When the recording device was invented and appeared for the first time in the late 19th/early 20th century, people thought it would result in new creative elements. Whereas, in my opinion, when men recorded their voice on this device and listened to it over and over again for the first time in history, and thus owned the repeating process for the first time, many uṣūl and melodic patterns were fixed in the maqām, and the singers who came later relied on the original recordings of certain old singers who had become symbols. Until today, people go back to what these old singers did because they see early recordings as a source to learn and to interact. If the recording device had not been invented, interacting and learning, i.e. learning/inheriting from fathers and ancestors, would have developed further. For more than one century now, maqām are the same. They did not change since they were fixed through the voice-recording device. We can discuss this complicated issue about the negative and positive aspects some other time as it necessitates a long discussion.

Wasn’t oral tradition the rule to teach and bequeath this art from one generation to another?

Nowadays?

Before the recording era.

Of course. All I am saying is that the only way, before the recording device was invented, was to learn from fathers and ancestors. It was the only teaching media, a normal process in any period of our History before modern technology… Everything was inherited through learning from fathers and ancestors.

So, recording codified this process and gave ancestors a voice that could be heard.

Recording gave grandfathers a voice and fixed it, and gave them the leading position. I learned maqām from recordings.

Not with a teacher…

In the beginning, I had no teacher. My father as well as my uncles on my father’s and on my mother’s side all sang maqām. I grew up in a maqām environment. I acquired maqām –heritage is acquired, not given– naturally and spontaneously in this milieu/environment created by my family and my region, whereas I memorized the uṣūl of maqām added to many maqām, the first time, through recordings. I also started to create my own maqām out of the variety of the recorded material. Time went by and I ended up joining the Iraqi Institute of Musical Studies as a music student, and learning about the pieces, the periods…etc., until I finally understood what I had learned, since I could not explain until then the melodic patterns I already knew. The Institute helped me learn things by their names, until I could recognize the melodic pattern of a certain maqām.

So, in short, it is a matter of personal effort: relying on recordings, one may either learn to be creative or to repeat like a parrot.

Indeed.

Here is what I did Mr. Mustafa, for the benefit of the new generation: I memorized maqām like a parrot, including those of Muḥammad al-Qubbanjī –all of them–, Yūsuf ‘Umar –some–, and ‘Abd al-Raḥmān al-‘Azzāwī –some–. After that, my instinctive and spontaneous thinking as a young man, free from any external influence –as I had no teacher, because my region and my family were very conservative, and I had never met a real artist, on the radio or on TV, before I entered the world of singing in the Baghdad museum early in 1973. At the age of 20, I still did not know any famous singer. I had learned everything I knew from my family who performed maqām while they were not experts–…

…So here is how I proceeded: I would choose for example the maqām ḥakīmī and listen to its interpretation by different singers such as ‘Abd al-Raḥmān al-‘Azzāwī, Yūsuf ‘Umar, al-Qubbanjī, or Najm al-Shayakhlī, then I would analyse how each one of them dealt with the melodic patterns, and pick out the similarities and differences (free variations/initiatives). I had to abide by the elements they agreed on and that had become fixed. So I created my own maqām, and I did not introduce myself to the media. I sang maqām in new qaṣīda –not the known qaṣīda interpreted by others– until I surprised the audiences and achieved great success with my performances at the Baghdad Museum.

(♩)

Dear listeners,

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

We thank Iraqi muṭrib and musicologist Mr. Ḥusayn al-A‘ẓamī.

We listened to two maqām today:

- First, the ḥawīzāwī maqām performed by Muḥammad al-Qubbanjī and his musical band;

- Second, an instrumental piece recorded during Cairo’s 1932 Congress of Arab Music, played by ‘Azūrī Hārūn (‘ūd).

Please note that AMAR is not the unique source of the recordings heard in our episodes dedicated to the Iraqi maqām. Many were borrowed from other disc libraries including Prof. Aḥmad al-Sabkī’s, and the full recordings of Cairo’s 1932 Congress of Arab Music edited by Mr. Jean Lambert and published by the National Library in Paris, added to the music libraries of Sheikh Khālid āl Thānī and Mr. Aḥmad al-Ṣāliḥī. We thank them all.

We will meet again in a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

“Durūb al-Nagham”.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)