The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Today, we will resume our discussion about the “maqām ‘irāqī” with Iraqi maqām muṭrib and music researcher Mr. Ḥusayn al-A‘ẓamī.

Let us talk about the maqām as a musical/melodic pattern.

To me, and to any listener, the maqām includes an introduction, a trunk/body, and a conclusion, the same as any waṣla in our umma (nation)… the waṣla of both Arabs and non-Arabs.

The maqām consists of:

- An instrumental introduction;

- A taqsīm;

- A vocal improvisation;

- Quasi-fixed singing;

- Fixed/set singing.

Could you describe the appellations and the structure of maqām? Do they all have the same structure or does it change from one maqām to another?

For a start, bring your ‘ūd and stop recording, so we can begin…

We talked about the structuring or shaping of the Iraqi maqām in the recent centuries, i.e. when its dimensions became clear (beginning, body, end) and it reached, towards the end of the 19th century, the peak of its final classical structure made of five elements/sections.

Let us describe these five elements, and select a specific maqām to apply this explanation. Note that these five elements must be present in all maqām, except for very rare cases where there are only four.

Let us take the maqām banjkāh –within the scale of the maqām rāst–.

The 5 sections are as follows:

First, the “taḥrīr”: It is the “expression” or “expressive” facet of the maqām, i.e. the same as “Yā lēli, yā lēli, yā lēli” preceding the sung poem in the mawwāl ‘arabī. It consists of words outside the poem, bearing no relation to the latter’s text.

It consists in using the voice as a musical instrument… vocal taqsīm.

Exactly. The muṭrib gets ready to sing the qaṣīda and prepares the listeners for this passage.

He performs salṭana in the maqām.

Salṭana, exactly… It is called taḥrīr in the Iraqi maqām.

Let us listen to the maqām banjkāh –from the maqām rāst’s scale–. We will only play the taḥrīr now. The other sections will follow one by one, as we go, to illustrate the content of the Iraqi maqām…

(♩)

This was the taḥrīr, i.e. the first of the five sections constituting the maqām irāqī.

I sang “Amān amān”… words that bear no relation to the qaṣīda I will sing now.

The second section is the “qiṭa‘ and awṣāl” (instrumental parts and vocal waṣla), i.e. jins or scale modulations, from one jins to another, from one scale to another, within the frame of the sung maqām.

The banjkāh note.

Yes… Within the banjkāh note, i.e. he goes back to the banjkāh at the end of the modulation. The performer modulates to any other scale or jins then goes back to the sung maqām. And, since we are singing to the maqām banjkāh, then we must go back to the banjkāh.

The taḥrīr is followed by the qaṣīda.

Here is how the modulation to the “qiṭa‘ and awṣāl” is done…

(♩)

We modulate a little to the ḥijāz with a jins ḥijāz, then go back to the banjkāh…

(♩)

We have completed the taḥrīr and the “qiṭa‘ and awṣāl”.

The third section is the jalsa that means “descent”. The jalsa’s descent to the qarār (the jalsa’s qarār, not any qarār) –each maqām has a different jalsa, yet they all indicate the descent in singing– follows a specific melodic pattern: the singer is not allowed to descend freely to any qarār within the musical scale or in singing. The jalsa’s melodic pattern is specific to the chosen maqām. The qarār has a specific melodic pattern.

Let us continue and listen to the maqām banjkāh jalsa …

(♩)

In this jalsa, the banjkāh is positioned on the Fa, i.e. the jahārkāh. In the banjkāh jalsa, we descend from the fourth to the Do… (♩) then settle on the Fa, i.e. the fundamental position of the maqām banjkāh.

Note that this jalsa first inspired the singer, then the instrumentalist who must know the details pertaining to the pattern of the Iraqi maqām… not any instrumentalist knows how to deal with the maqām’s specific characteristics, typical fixed melodic patterns…etc. He must understand that the jalsa is an action requiring a reaction. This reaction is called the mayāna, i.e. the jawāb, and constitutes the fourth element/section.

So the jalsa descends and its reaction is the jawāb…

(♩) (The fifth section is the taslīm that resembles the jalsa)

This was an example illustrating the five sections specific to each Iraqi maqām: taḥrīr; “qiṭa‘ and awṣāl” (that must not necessarily be alike, but must be present); jalsa (its melodic pattern is different from the banjkāh jalsa’s for example); mayāna (the banjkāh mayāna is different for the mayāna in another maqām); taslīm (also different depending on the maqām). The elements/sections, present in each and every maqām, are different depending on the maqām.

We chose the maqām banjkāh that is the easiest maqām as an example to explain the melodic patterns and the uṣūl of the Iraqi maqām.

Easiest or clearest?

Clearest indeed. We chose a maqām that is used to sing literary qaṣīda, and that is thus obviously clearer and closer to Arabs…

(♩)

We have just listened to the maqām banjkāh, including: ‘ūd taqsīm, dialogue between ‘ūd and jawza, qānūn, sanṭūr, …etc., no percussions.

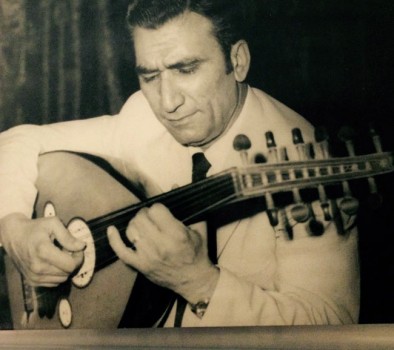

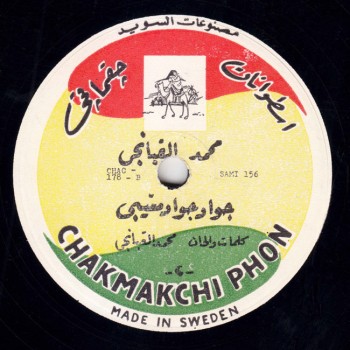

The recording is of Mr. Muḥammad al-Qubbanjī and his jawq including ‘Azūrī Hārūn (‘ūd), Yūsuf Za‘rūr (qānūn), Ṣāliḥ Shumāyil (violin known in Iraq as the jawza because it bowl, like the rabāba’s, is made of half a coconut shell), and Yūsuf Bātū (sanṭūr). Their performance displaying the five sections of the Iraqi maqām (detailed earlier) is a model performance, knowing that this recording is among those of the 1932 Congress of Arab Music. Note that each instrument displays its own measure or dūzān: the ‘ūd and the jawza (violin) display open strings, while the sanṭūr and the qānūn display all their strings.

This was the dūzān of the maqām banjkāh from the perspective of each instrumentalist.

You had a question concerning the second part?

Is the musical introduction compulsory in the Iraqi maqām? I am referring to the introduction, not to the taqsīm: the introduction such as the bashraf, the samā‘ī, or the dūlāb.

I remember the question now…

There is an important point: Iraqi maqām singing in the 19th century, i.e. during the dark ages in Iraq that started at the fall of the Abbasid Dynasty, played the first role, while music played the second role. Music started playing its rightful role within Iraqi singing, i.e. within the unified anthology of maqām singing in Iraq including mountain singing and Bedouin singing, in the early 20th century. The start of the recording era triggered the musicians’ awareness of History as they now realised their performances could be recorded and could live on. Consequently, they decided to codify this singing. Until then, singers used to start performing and the instrumentalists followed them. Now was the time –as a result of this cultural evolution– to develop a mutual understanding between the instrumentalists and the singer: the introduction was structured, followed by some leeway for taqsīm –the instrumentalist now started before the muṭrib who would resume the dialogue… I am talking about the maqām whose music is not rhythmical but dialogal –a dialogue between the instrumentalist and the singer–.

You are referring to the rhythmic cycle of course… as all Arab music is rhythmical.

We will analyse this point when we reach it… We are talking now about the dialogal maqām, about the dialogue between the instrument and the musician. In the early 20th century, i.e. at the start of the recording era, music started playing the main role in the piece, in the introductions, in the musical dialogues… There was now a beautiful interaction between song and music.

Let us listen to another example illustrating the relation between music and the individual performer or muṭrib of Iraqi maqām, recorded around 15 years after the previous recording, also by Muḥammad al-Qubbanjī accompanied by the jawq of Mr. Jamīl Bashīr. The maqām is the khanabāt. Note the taqsīm played by Jamīl Bashīr accompanying him continuously. We will hear the full maqām with its taqsīm, its 5 sections and its basta…etc. Also note –this is a personal remark– the marvellous harmony with the female biṭāna…

We reach the end of today’s episode of “Durūb al-Nagham” with al-Qubbanjī’s maqām khanabāt.

We will meet again in a new episode.

We thank Mr. Ḥusayn al-A‘ẓamī and all those who helped us obtain these recordings, added to the recordings of AMAR.

“Durūb al-Nagham”.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)