The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Today, we will be resuming our discussion about musical dialogues.

Upon the return of record companies after WW1, there was an enthusiastic rush towards singing duos, or rather trios or larger singing ensembles.

Might this be because the musical theatre had spread then?

…Or maybe because they were now able to record more than one voice at the same time.

Electricity did not exist yet!

True, yet there were now several mics recording at the same time, i.e. several mics could be connected to one needle: two or three mics could be installed, and thus several voices could be recorded at the same time. One was not forced anymore to step aside in order to allow another to record.

The recording technologies had evolved and, as you have pointed out, the musical theatre had spread a lot after WW1, mainly to promote the emerging national movement in Egypt at the time, i.e. the events of the 1919 revolution.

Who represented this movement?

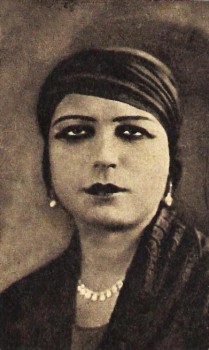

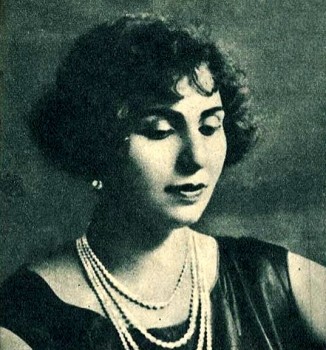

On the recording level, all of them including Sayyid Darwīsh and Ḥayāt Ṣabrī, Munīra al-Mahdiyya who sang duets with several artists, notably with Zakariyyā Aḥmad who sang many himself. There is a full collection of recordings by Zakariyyā Aḥmad and Ratība Aḥmad, as well as by Sayyid Darwīsh and Ḥayāt Ṣabrī.

Who goes back the farthest in this issue?

We can’t tackle this subject as all of them after WW1, between 1920 and 1921, made discs with the record company they had a contract with:

Sayyid Darwīsh and Ḥayāt Ṣabrī, who had of course sung together before the 1921 Odeon campaign in which Sayyid Darwīsh also recorded, did not record until late 1921/early 1922. All of Sayyid Darwīsh’s previous recordings made by Meshian and Baidaphon only included solo singing. He only recorded dialogues during the Odeon campaign.

Munīra al-Mahdiyya also started recording duets in 1921/2/3.

The same goes for Zakariyyā Aḥmad and Sitt Ratība.

Even the duets of ‘Abd al-Wahāb and Samḥa al-Maṣriyya were also recorded during this campaign, i.e. the Odeon campaign in which Sayyid Darwīsh recorded in 1921/22.

Did this result in a single specific musical form, or in numerous styles and structures/patterns?

There are as many structures/patterns as there are musicians. Let us take Sayyid Darwīsh and Ḥayāt Ṣabrī’s “ ‘Ala add el-lēl mā yṭawwil” recorded on two sides of an Odeon record: a balanced dialogue clearly depicting a scene between two lovers remembering what happened between them the night before and trying to repeat that night, “Ammā dī ḥa’’a kānit lēla fī ghāyit el-ri’’a” (It was indeed an extremely sweet night)…etc. It is a balanced dialogue between two main characters: they are equal, none is dominating the other.

…And musically?

Musically too… none is dominating the other.

Were they accompanied by a takht?

No. We are talking about Odeon’s band accompanying Sayyid Darwīsh and including a piano, a flute, and a violin. I am not referring to the musical element rather than the performance element itself. If we tackle the musical element, we will notice that the band is playing a minor while Sayyid Darwīsh is singing to the ‘ushshāq, and thus that there is a big difference between his notes and those played by the band. Only Sheikh Sayyid could have explained this choice that he surely made consciously.

But this is not the subject of our discussion… Let us talk about the performance itself. In the dialogue with Sayyid Darwīsh, no one is dominating the other, even though he is the composer. Everything is fully fixed, leaving no freedom for improvisation or variation… simply because it is a dialogue: one must stop talking and allow the other to answer him. Knowing that the accompanying ensemble is the band that Sitt Ḥayāt Ṣabrī, at the 1932 Cairo Congress of Arab Music, called “orchestra”, i.e. the trio whose only Arab member was Jamīl ‘Uways (violin), while the piano and the flute were played by foreigners, those could surely not keep pace with him in his improvisations. So everything was fixed from a to z. There is no leeway for improvisation. Even the variations are to the exact same melody he composed.

Ok. Let us listen to “ ‘Ala add el-lēl mā yṭawwil”…

(♩)

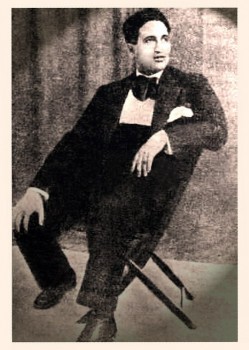

What distinguishes Zakariyyā Aḥmad who was a contemporary of this period?

Zakariyyā Aḥmad was a “joker” who worked at everything. In the dialogue “Wa‘dī ‘alēki yā ghandūra” that he composed and that he recorded with Munīra al-Mahdiyya, he respected her wish to be a star, while keeping in mind his Sheikh status. So he kept his margin as a Sheikh while respecting at the same time Munīra al-Mahdiyya’s margin as a star he must not clash against. In spite of all this, the band accompanying him –that it seems he was trying out– is the one including a piano, a flute, and a violin that accompanied Sayyid Darwīsh. While this time the recording was made by Baidaphon, not by Odeon.

The style I would like to talk about… in fact, I do not know if he recorded with Ratība Aḥmad before Munīra al-Mahdiyya… the first style in which he recorded with Munīra al-Mahdiyya is closer to Sayyid Darwīsh’s than to the style of Zakariyyā Aḥmad whom we will listen to in a short while. He also kept a margin for improvisation despite the fully fixed elements: it is closer to improvisation than to variation, still he does not go entirely outside the text, and allows Munīra al-Mahdiyya to take initiative in the melody he composed.

Let us listen to “Wa‘dī ‘alēki”…

(♩)

The second style of Zakariyyā…

And his most important style, isn’t it?

…is the style that will distinguish Zakariyyā Aḥmad from the rest. If I personally had a wish concerning dialogue singing, I would have wished it to be like this: it includes a scene, fixed and known aspects on the lyrics’ level, a fixed melody…etc., yet freedom for the muṭrib and for the takht / the instrumentalists, to take initiative.

If you will allow me, I would like to listen to two excerpts instead of one:

First, “Yā bakhtuhum” recorded by Polyphon and performed by Zakariyyā Aḥmad and Ratība who tried to render a scene similar to Sayyid Darwīsh’s scene in “ ‘Ala add el-lēl mā yṭawwil”, i.e. two persons remembering what happened between them, then she inviting him to visit her at her home where “Nīna and my father will be asleep”, then him sneaking in and both of them having a beautiful love talk.

Sheikh Zakariyyā remains Sh8eikh Zakariyyā …

There is a margin for improvisation, yet it is not completely free as he seems to be still wondering what to do.

Let us listen to “Yā bakhtuhum”…

(♩)

Dear listeners,

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

We will meet again in a new episode to resume our discussion about Musical Dialogues.

This episode was presented to you by Mr. Kamal Kassar.

“Durūb al-Nagham”.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)