The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Sama‘ ”.

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Sama‘ ”.

“Sama‘ ” discusses our musical heritage through comparison and analysis…

A concept by Mustafa Said.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Sama‘ ”.

Today we will resume our discussion about the bashraf (pre-composed instrumental form with often quite long binary rhythmic cycles, played as a prelude to the waṣla. The structural pattern of the bashraf generally alternates four khāna-s and the taslīm/ritornello. There are other types of semi-composed bashraf-s alternating one or two composed sections and an improvisation in a binary rhythm responsorial between the instrumentalists) qarah baṭāq sikāh by kimānist Khuḍr Āghā, arabised by a great musician whose name we unfortunately do not know. We do not know either when this bashraf was arabised, yet we think it was not too long after it was created, based on data some of which we already discussed. The remaining data will be discussed today or in our next episode.

The written dialogues and the improvised taqsīm-s (modal improvisation):

We said that the dialogue evolves from one khāna (section) to the other. The first khāna includes a 16-beat’ dialogue, i.e. a half measure or a full measure since the rhythmic cycle is short, the second one twice the length of the first, and the third one twice the length of the second, i.e. the first khāna being 16-beats’ long, the second would be 32-beats’ long, and the third khāna in full would constitute a dialogue.

We have also discussed the taslīm (ritornello) and the lāzima (chorus):

If we consider that the lāzima between the second and the third khāna-s can be a lāzima …

(♩)

Or if we consider it as a simple taslīm between the khāna-s, free of a lāzima, i.e. that the bashraf does not include a lāzima separating the khāna-s.

Or if we consider that the measure is short, then there should be a full fast 32-beats’ lāzima separating the khāna-s …

(♩)

All this is unimportant… We will talk about khāna-s in another discussion.

This episode is dedicated to the taqsīm-s and the dialogue. Let us tell again about the progress of the dialogue. We will listen to the dialogue at the end of the first khāna, then to the dialogue in the middle of the second khāna, then to the dialogue that is the third khāna in full, all played by ṭanburist Jamīl Bēk and ‘ūdist Shawqī Afandī …

(♩)

Let us tackle some elements of the dialogue that will help us to compare with the taqsīm-s:

In the first khāna, the ‘ūd (lute) and the violin play the same thing, yet the violin performs the taslīm at the sixth step of the maqām (musical key), i.e. the kardān that is the jawāb (high notes. treble) rāst …

(♩)

And the ‘ūd performs the taslīm at the fourth step of the maqām, i.e. the sikāh, or the ḥusaynī or fourth step of the maqām, in the Turkish version …

(♩)

The difference is at the end of the phrase, not at its beginning.

In the second khāna, both play the same phrase exactly in both the istilām and the taslīm. Also note that the second khāna in full is played to the jawāb of the maqām, i.e. the awj, at the ninth step of the maqām or the phrase …

(♩)

At the eighth step of the maqām, the second phrase reaches the fifth step of the maqam in order to perform the taslīm to the lāzima at the sixth step of the maqām …

(♩)

We have heard both.

There are two phrases: The first khāna consists of one phrase, and the second khāna consists of two phrases. The third khāna is a dialogue that includes four bow phrases and four plectrum responses. It starts at the fifth step of the maqām …

(♩)

And the ‘ūd answers to the same maqām …

(♩)

He then modulates to the seventh step of the maqām in a phrase that reminds us of the phrase in the first khāna …

(♩)

And he answers him to the third step of the maqām …

(♩)

In both cases, the response is one fifth lower than the question.

After this, he starts with a higher seventh step ascending to the jawāb of the maqām …

(♩)

Awj …

(♩)

He responds with the same phrase to the qarār (low notes. bass) of the maqām, not the jawāb, i.e. Jamīl Bēk Ṭanbūrī plays to the jawāb and he answers to the qarār …

(♩)

Again, in the fourth phrase, he starts from the fifth just like he did at the beginning of the third khāna …

(♩)

He also concludes to the qarār of the maqām with a descending fifth. Jamīl Bēk Ṭanbūrī starts to the fifth step of the sikāh, i.e. the awj, and the ‘ūd answers to the qarār of the maqām …

(♩)

The purpose of this analysis is the following:

Let us listen to this phrase performed by Ibrāhīm Afandī Sahlūn …

(♩)

This was in the first khāna in relation to which we mentioned that he transformed the dialogue into a collective performance.

Now, let us confirm that this phrase of the dialogue was taken from the third khāna, not from the first khāna that is similar to it …

(♩)

He answers to the third step of the maqām …

(♩)

Because he plays exactly like ṭanbūrist Jamīl Bēk, even if he probably played the bashraf before ṭanbūrist Jamīl Bēk’s recording was made, Ibrāhīm Sahlūn had surely heard its Turkish version, or heard it played live by someone who had decided to play this instead of the first khāna. I think that he most probably heard the bashraf played by a Turkish jawq (ensemble), either by ṭanbūrist Jamīl Bēk or by another.

Let us tackle some phrases that were played as taqsīm-s, starting with the first phrase in the second khāna …

(♩)

This same phrase was played by the violin and by the ‘ūd, once to the jawāb and once to the qarār.

Let us listen to Ḥāj Sayyid al-Suwaysī and al-Qaṣṣabgī …

(♩)

Ḥāj Sayyid al-Suwaysī had either heard it played by someone who was influenced by the Turkish version, or had heard it himself played by a Turkish band.

Had Muḥammad al-Qaṣṣabgī also heard it played by Turks or by Ḥāj Sayyid al-Suwaysī? I think he probably heard it played by Ḥāj Sayyid al-Suwaysī, … but then again maybe not.

Let us take the beginning of the third khāna …

(♩)

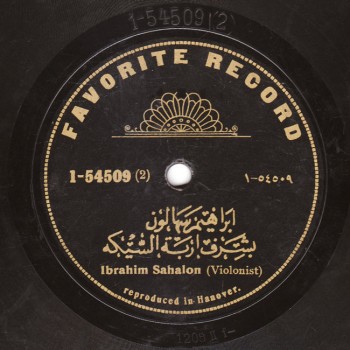

Let us listen to Ibrāhīm Sahlūn’s Favorite recording, then to Sāmī al-Shawwā’s recording made 23 or 24 years later with Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād.

Let us listen to this phrase …

(♩)

The same …

Let us now listen to ‘Alī ‘Abduh Ṣāliḥ who plays most phrases in the same manner, as follows …

(♩)

It is the same phrase of the third khāna that he start and ends with …

(♩)

Even the way they play the taqsīm-s is influenced by the Turkish jawq-s’ playing, or by their travels to Topkapi among other places.

Talking about Topkapi, let us end today’s episode with a pre-WW1 Baidaphon recording, knowing that Baidaphon was established during the Ottoman Empire.

Let us listen to this old pre-WW1 Baidaphon recording with Ibrāhim Afandī Sahlūn (kamān), Manṣūr Afandī ‘Awaḍ (‘ūd), and ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd Afandī al-Quḍḍābī (qanūn).

A beautiful piece part of which we had played, adding that the full-dialogue first khāna was played collectively, knowing that the phrase was taken from the violin phrase in the third khāna, as mentioned earlier.

Let us listen to the full recording of this wonderful takht …

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Sama‘ ”.

We will meet again in a new episode to resume our discussion about kimānist Khuḍr Āghā’s bashraf qarah baṭāq sikāh, arabised by an unknown great musician.

“Sama‘ ” was presented to you by AMAR.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)