Muwashshaḥ “Lammā badā yatathanna”’s author is unknown. Its melody is attributed to Sheikh Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Raḥīm al-Maslūb and composed to the nahawand maqām, a sub-maqām of the ‘ushshāq maqām.

“Lammā badā yatathanna

Ḥibbī gamāluh fatannā

Aw mā bilaḥdhuh asarnā

Ghuṣnun thana ḥīna māl

Wa‘dī wa yā ḥīratī

Man lī raḥīm shiqwatī

Fī al-ḥubbi min law‘atī

Illā malīk el-gamāl”

A comparison between two recordings:

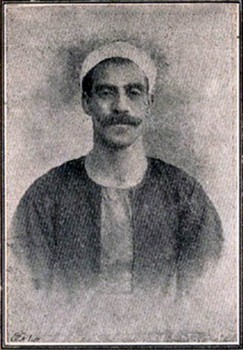

The first is Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s version recorded by Gramophone around 1910 on one side of a 25cm record, order # G.C.14/12321, matrix # 1314Y.

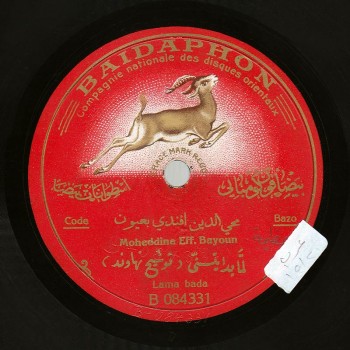

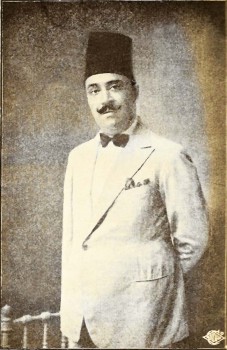

The second is Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn’s recorded by Baidaphon around 1924 on one side of a 27cm record, disc # B/084331.

In the world of Arabic music, muwashshaḥ “Lammā badā yatathanna” almost holds the same position as the qawmī hymn. Let me explain: during a certain period, whoever wanted to save Arabic music from the hell of “stagnancy and backwardness” caused by the 3/4 tones and the lack of harmony -all the reasons considered, for more than a century to this day, to be behind this backwardness- resorted to this muwashshaḥ because it can be compared to the refined world music, unlike most backward Arabic melodies. And also because this musical piece brings Arabic music closer to the more evolved symphonic music. Consequently, it stood as a safe haven for the music professionals who wanted to push Arabic music forward, going from orchestral arrangement to opera singing. When new trends appeared such as Jazz and Rock..etc, this is the muwashshaḥ music professionals resorted to.

Unfortunately, the versions of this muwashshaḥ available in institutes and academies do not convey its true melody. The exact melody of this muwashshaḥ is not a set melody. It is largely based on the performer’s interpretation. Both recordings we will analyze today clearly highlight those differences, starting from their beginning. Let us listen to both versions of this muwashshaḥ’s beginning, the first one interpreted by Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī and the second one by Muḥyiddīn Afandī Ba‘yūn.

First: the muwashshaḥ “Lammā badā yatathanna” is certainly not the slow romantic version we know. It is a pure classical Arabic melody. In “Ḥibbī gamāluh fatannā”, note the difference between the nawā āthār or ḥiṣār in Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s interpretation, and the bayyātī in Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn’s interpretation. The difference lies in the interpretation of the melody. Regardless of the differences, both versions are beautiful and do not harm or distort in any way the content of the muwashshaḥ.

There are two resembling adwār followed by the khāna that is slightly –not very– different from both adwār. The khāna is: “Wa‘dī wa yā ḥīratī / man lī raḥīm shiqwatī”. There is a relative difference between both interpretations of this khāna. In fact, this khāna was the part that highlighted the most the muṭrib’s role and personal improvisations of the muwashshaḥ. That is why they used to compete –amicably– in order to find out who would best convey this muwashshaḥ’s content. Let us listen to “Wa‘dī wa yā ḥīratī” interpreted by Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī and by Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn.

The course followed is the same in both interpretations and they both came out of the same core. There is no great difference between them. The only difference lies in the interpretation and the details. The accompanying ensemble includes the same violinist. And even if the qānūnist accompanying Sayyid al-Ṣaftī is ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī and the one accompanying Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn is Zakī Afandī, the interpretation concept is practically the same. Muḥyiddīn Afandī Ba‘yūn’s performance is higher-strung because there is an approximately 15 years’ gap –less actually– between both recordings. In the second recording, it seems to us that the idea of recording had become less foreign: the first recording was made only 10 years after the invention of records. There was a kind of fear from the gramophone; music professionals were not yet well acquainted with this concept. When the second recording was made, music professionals were more moderate and more confident. They knew very well what they were going to record, on which side of the record, and in what way. That is why Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn’s performance is higher-strung. Let us listen to both singers’ interpretations of the rest of the record. As we mentioned, in Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s recording, the concept of the gramophone and the idea of recording were still foreign: therefore, note that Sāmī al-Shawwā was attempting to produce a taqsīm while ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī was interrupting him. Sāmī Afandī al-Shawwā had to stop out of respect for the older ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī. Thus, ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī performed his taqāsīm and Sayyid al-Ṣaftī gave marvelous layālī. Let us listen to this entertaining quiproquo between Sāmī al-Shawwā and ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī.

In the second recording, note that the taqāsīm are organized according to each performer’s role. For example, Sāmī al-Shawwā’s taqāsīm to the bamb are pre-organized. They are not performed in order to fill time; the performers had already been informed as to the remaining time on the record. Sāmī al-Shawwā’s produced great improvised taqāsīm to the bamb that were very much appreciated by Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn. Let us listen to this passage that clearly shows the respect among the members of the takht. It is not about a singer versus a member of the band, or a question of a unique star and the sub-performers, it is simply about a cohesive and harmonious group performance.

As a conclusion, let us listen to both versions and note the difference between the two totally different instrumental introductions. The band accompanying Sayyid al-Ṣaftī started off with the “‘abbās march”, while the one accompanying Muḥyiddīn Afandī Ba‘yūn started with a nahawand dūlāb.

Let us listen to the difference between both interpretations of the muwashshaḥ: Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s experience and calm versus Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn’s enthusiasm and impishness. Let us listen to the layālī following each muwashshaḥ and to the taqāsīm of Sāmī al-Shawwā and ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī. Let us listen to the different interpretations of the same melody by Sayyid al-Ṣaftī and by Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn, and the different instrumental accompaniment. Let us listen and conduct a detailed analysis while listening. I am sure you will discover much more than what I have tried to explain.

Thank you for listening.

We will meet again in a new episode of “Sama‘ ”.

Our next episode will bring a surprise concerning the set and the variable elements, an issue we will discuss with Dr. Frédéric Lagrange.

“Sama‘ ” was brought to you by the Arab Music Archiving and Research.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)