The third phase of the dawr’s evolution started with a generation of composers that included mashāyikh students, singing theatre (operetta) students, and other students who gained their learning and knowledge from both. Sheikh Abū al-‘Ilā Muḥammad is a great representative of the Nahḍa school students. He performed and composed adwār while his main focus was the qaṣīda that he played a significant role in developing. This will be the subject of another discussion. The first who went on composing adwār in the generation following Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī’s and Dāwūd Ḥusnī’s generation is Sheikh Sayyid Darwīsh. He composed ten adwār, nine of which he recorded with his own voice while the tenth was recorded in Muḥammad Afandī Nūr’s voice. All ten were recorded on four 27cm record sides, which may indicate that the Sheikh took into consideration the record duration while composing them, or that the adwār had been composed for recording purposes, more than as works dedicated for live concert performance. Thus, the first characteristic of the third generation’s dawr relates to its recording: for example, the composition of the dawr took into account the turning of the record, i.e. the changing of the side, as well as the record duration of the dawr’s standard version. Starting then, any addition the singer decided to perform during a concert was his own responsibility, while the recorded version was considered as the standard one. This issue affected the concept of the strict pattern: some of the tafrīd and waḥāyid phrases sung individually by the performer became imperative, as well as the taslīm from the tafrīd to the henk, from the henk to the waḥāyid, and from the waḥāyid to the final part that all became pre-composed. This reduced the performer’s space for improvisation. All these did not characterize Sayyid Darwīsh’s adwār: we can hardly make them out throughout all his adwār, apart from his last three adwār. He recorded seven with Mechian between 1915 and 1917, and three (mentioned earlier) with Baidaphon in 1921. Out of the seven adwār recorded by Mechian, only dawr “Fī shar‘i mīn” –the last dawr recorded by Mechian– includes all the above-mentioned –still barely noticeable– elements. However, all the adwār recorded by Baidaphon include the same elements, i.e.:

The madhhab:

Made of three phrases separated by pre-composed instrumental articulations that constitute transitions from one sub-maqām to another and maintain the adwār’s fixed maṣmūdī kabīr (8 pulses) rhythmic cycle. The phrases of the madhhab gradually display the maqām until reaching its peak in the third phrase.

The dawr and its components:

The tafrīd: a series of phrases starting with a phrase paralleling or addressing the maddhab’s first part. Each one of these phrases is composed to a different sub-maqām, and in some rare cases to a whole different maqām. Each one of these tafārīd is repeated twice with slight variations that are not sufficient to imply a new melodic phrase. There is also a noticeable possibility for istirsāl (prolongation) before the transition to the tarannum. This istirsāl seems to be specific to live performances where a pre-composed phrase constitutes a transition from the tafrīd to the henk tarannum. This phrase is thoroughly memorized by the biṭāna members as it indicates the shift to the tarannum phrase.

The tarannum or henk: relatively long pre-composed phrase chanted by the biṭāna members. In this type of adwār, it only includes āhāt and no layālī. After the tarannum phrase is performed by the biṭāna, the soloist sings a standard pre-composed phrase that also consists of āhāt, followed by the biṭāna repeating the same phrase they had performed before the soloist’s performance. We deducted that the phrase performed by the soloist is pre-composed because it is repeated twice and is always preceded and followed by the biṭāna members’ phrase. Still, the biṭāna’s is open, probably to allow the performer to add new phrases at whim. Later recordings of these adwār performed by others display all the above-mentioned points.

The waḥāyid: another display of the maqām after the tarannum phrase, this time in a responsorial form between the soloist and the biṭāna, the performer this time beginning before the biṭāna. The reason behind this is that the performer starts off the waḥāyid after the biṭāna finishes the repetition of the tarannum phrase, instead of adding a variation with a new phrase. We can easily make out the waḥāyid part when listening to the repeated lyrics of the dawr that was only constituted of āhāt in the tarannum. The waḥāyid section is made of three instrumental articulations-free consecutive phrases displaying the maqām. The soloist leads the biṭāna from one phrase to another in a quasi-improvisation style then repeats the pre-composed phrase at the end of the tafrīd section, or a pre-composed phrase derived from it.

The conclusion: new phrase that can be either fast-paced, or inspired from the madhhab’s third phrase, i.e. the madhhab’s conclusion, or totally new. It is performed by the singer, either individually or with the biṭāna. It takes the maqām from its peak back to its original position.

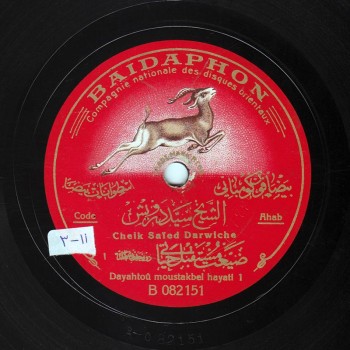

As an example of this style, here is dawr “’Ḍaya‘ti musta’bal ḥayātī’” written by Yūnis al-Qāḍī, composed and sung by Sheikh Sayyid Darwīsh to the kārjahār, a sub-maqām of the bayyātī maqām whose scale ordrer is similar to the bayyātī shūrī’s but with a different pattern. The dawr was recorded by Baidaphon in 1921 on two 27cm records, # B-082151, B-082152, B-082153, B-082154. Takht Sheikh Sayyid Darwīsh, Sāmī Afandī al-Shawwā, ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd Afandī al-Quḍḍābī and Maḥmūd Afandī Raḥmī.

The performance of the dawr certainly varied throughout the different phases of its evolution. Those changes are equally relative to the recordings and to live performances. There are no proofs confirming the form of the dawr in its different stages when performed in live concerts, if we do not consider the waṣlāt recorded by the Egyptian Radio in the 1940s and 1950s as a dead reflection of the live performance. Although the duration of the recording was relatively open, the relation between the performer and the audience is completely lost: “the performer now addresses the microphone instead of interacting with the listeners” as Ṣāliḥ ‘Abd al-Ḥayy put it. On the other hand, we can confirm that the traditional form of the dawr allowed the munshid a freedom of improvisation in parts following the madhhab, while abiding by a specific pattern fixing a simultaneous performance of the tafrīd, the tarannum and the waḥāyid. Despite the differences in a certain dawr, for example a dawr recorded twice by Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī with two different styles as to the parts following the madhhab, we find an almost exact resemblance between two different recordings of another dawr performed by him. Consequently, we find ourselves wondering about the relation between the composer of the dawr and its performer. Who wanted two different styles for the dawr? Who wanted to highlight the almost exact same style in two recordings of the same dawr? Sheikh Yūsuf or the composer? The adwār in the first quarter of the 20th century, for example the dawr we just listened to that was recorded by many performers after Sheikh Sayyid Darwīsh in private and public concerts and even with different radio stations, were performed in the exact same manner Sayyid Darwīsh performed them on the Baidaphon records. Other performers included variations while abiding by the set pattern. It is said that some affirmed having listened to Sayyid Darwīsh singing dawr “Ḍaya‘ti musta’bal ḥayātī’” for more than an hour. Note that a performer of Sheikh Sayyid’s caliber would hardly repeat himself.

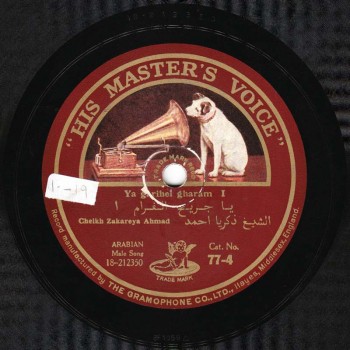

As to the composition process, there is no significant difference. We can find a dawr composed to a rhythmic cycle or another that are different from the traditional 4-pulse rhythm type. However, an important stage of the dawr reminds us of the impact of the religious inshād on secular singing. This is the case of dawr “Yā garīḥ el-gharām” written by Sheikh Yūnis al-Qāḍī and composed by Sheikh Zakariyyā Aḥmad to the ḥiṣār maqām. The Sheikh performed it with his biṭāna. We confirm our use of the word “biṭāna” here because its role in this case can’t be the same as the madhhabjiyya’s role, since there is no madhhab in this dawr: there are independent melodic phrases that the munshid links together with improvised phrases, exactly the same as in the tawshīḥ. The munshid links these phrases either with tarannum or by repeating the lyrics of the previously performed part. In the tawshīḥ, the munshid is free to follow the rhythmic cycle or to overlook it and only follow the rhythm of the lyrics. However, Sheikh Zakariyyā respects the rhythmic cycle throughout the transition phrases, maybe aiming at drawing a line between the tawshīḥ’s status in the religious inshād’s waṣla and the dawr’s status in the secular singing’s waṣla. It is as if Sheikh Zakariyyā were answering the question that emerged in the mid 1920s on whether the additional elements of the dawr were a result of Turkish influence, of Western influence, or of another influence. Through this dawr, the Sheikh reminds us that these new elements are inoculated additions emanating from the different religious traditions and which comply with most of the inshād’s components.

After the performance of the responsorial part between the munshid and the biṭāna from the start instead of the madhhab, Sheikh Zakariyyā jumps to a part similar to the waḥāyid although he did shift to the dārij rhythmic cycle while keeping all the other waḥāyid characteristics, i.e. the Q & A style exclamatory responsorial part between the munshid and the biṭāna. He then returned to the tawshīḥ form in the conclusion. Note that the maṣmūdī kabīr rhythmic cycle is totally absent in this dawr while Sheikh Zakariyyā’s adwār that preceded and followed “Yā garīḥ el-gharām” were to the traditional dawr form, such as the adwār he composed for Umm Kulthūm and Fatḥiyya Aḥmad, and even the adwār he sang himself approximately six years after “Yā garīḥ el-gharām”. On the other hand, he did break the rhythmic cycle’s rule in numerous adwār such as dawr “Yallī tishkī min el-hawa” whose madhhab is to the hindī dawr’s rhythmic cycle (7 pulses).

Let us then listen to dawr “Yā garīḥ el-gharām” performed by Zakariyyā Aḥmad with Takht Sāmī Afandī al-Shawwā, ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd Afandī al-Quḍḍābī, Sheikh Zakariyyā Aḥmad and Maḥmūd Afandī Raḥmī. It was recorded in 1928 by His Master’s Voice –daughter company of Gramophone– on two sides of a 25cm record, order # 18-212350, 18-212351, matrix # BF 1059, BF 1060.

Sheikh Zakariyyā Aḥmad was the last to quit composing adwār, if we consider the āhāt written by Bayram al-Tūnisī and sang by Umm Kulthūm in the 1940s as a type of dawr, and especially if we imagine the presence of the group of munshidīn accompanying the muṭrib. But let us leave this aside for now and resume our discussion with the last one to create a form within the evolution of the dawr’s form. It is Muḥammad Afandī ‘Abd al-Wahāb.

The inshād school undoubtedly affected ‘Abd al-Wahāb‘s singing because he belonged to it. He also graduated from the Oriental Music Club, the last pillar of the Nahḍa school the Club’s members supported, which also undoubtedly influenced his art. The final direct stage of his musical culture and learning was his appreciation of Sayyid Darwīsh whom he worked with, and who indirectly enriched ‘Abd al-Wahāb’s education. ‘Abd al-Wahāb also listened continuously to the different musical traditions, including the Turkish and the European, as well as to all new trends in his time. In spite of the direct impact of the European Classical Music traditions on Muḥammad Afandī ‘Abd al-Wahāb’s works, even before he composed adwār, he agreed with Sayyid Darwīsh as to putting limits to the importation of foreign elements into the dawr. Even though he added instruments that were foreign to the instrumental ensemble, the elements necessary to the takht’s performance were all there, unlike the performance of the large ensemble later on. The traditional instruments used in the takht before ‘Abd al-Wahāb were surely not considered traditional at the time they were added.

Now about the components of the dawr… There is barely any space to improvise any in ‘Abd al-Wahāb’s recordings. All the components are fixed including the tafrīd. ‘Abd al-Wahāb followed the same logic in all his recordings, including those of adwār, qaṣā’id, ṭaqaṭīq and even mawāwīl that are supposed to be fully improvised. We have reached this deduction after comparing the previously unreleased recordings of a same work made as practice exercises, and that ‘Abd al-Wahāb agreed to publish. Yet, we do have a copy of those..

Let us go back to the adwār of Mr. Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb as he fancied being called. On the instrumental level, there is an independent musical overture for each dawr it was composed for. It was not in the form of a dūlāb or a short phrase, but an introduction created as to be an overture to the whole work, and an integral part of it. We can also note the growing use of musical articulations including the phrases linking the madhhab’s vocal phrases, and the tafrīd that no longer existed as such but became fixed along with the instrumental articulations between the phrases interpreted by the sole singer. As to the singing, all components are fixed: the tarannum dialogue with the biṭāna includes elements filling the slight gaps in most cases. The waḥāyid remain the same, whether to the dawr’s rhythmic cycle, or to a different one that may have been shifted to, and the conclusion phrase is sometimes to the usual waḥda rhythmic cycle such as in some of the adwār of Sayyid Darwīsh, Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī and Dāwūd Ḥusnī.

Again, we do not know how Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb used to sing these adwār in concerts. It is said that he used to perform them in twice the duration of the recordings. It is impossible to guess how he did his improvisations, as he also stopped singing the adwār in the late 1930s, which deprived us of the chance to listen to any recording of a live performance of these adwār.

We will now listen to dawr “Ḥabīb el-alb ‘ūd shūf el-fu’ād” that is an example of this type. It was written by Amīn ‘Izzat al-Hagīn, composed and sang by Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb to the ḥijāz dīwān maqām.

Mr. Eliās Saḥḥāb says about this dawr: His voice here has reached full maturity and his melodic phrases are surprising. He barely settles on the ḥijāz maqām then quickly shifts to another maqām. His dealing with the expression “Ghulubti ashkī” in the tafrīd section to the ḥijāz maqām with a few shifts, then to the bayyātī in the responsorial section is unexpected and rare. It is actually unusual for the maqām of the tarannum to be different from the dawr’s maqām (bayyātī in this case). And finally, the fluid conclusion going back to the original maqām.

Let us now listen to dawr “Ḥabīb el-alb” ‘ūd shūf el-fu’ād” with Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb singing and playing the ‘ūd, accompanied by the madhhabjiyya and by Takht Jamīl ‘Oways (kamān), ‘Alī al-Rashīdī (qānūn), Riyāḍ al-Sunbāṭī (‘ūd), Gerges Sa‘d (nāy), Ḥusayn al-Nashshār (cello), and Maḥmūd Raḥmī (percussions). It was recorded by Baidaphon around 1931 on two sides of a 30cm record, # XXB-094503, XXB-094504.

We have reached the end of our discussion about the dawr for the time being.

Thank you for listening.

We will meet again in a new episode of “Our Musical System”.

This episode was brought to you by Muṣṭafa Sa‘īd and Ghassān Saḥḥāb in collaboration with Prof. Eliās Saḥḥāb.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)