The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

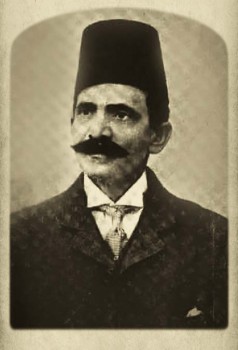

In today’s episode, we will resume our discussion about Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī.

My question is: Were any of Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s works recorded by others?

Let us talk about this some more. We already have, but let us discuss it further.

Many imitated Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s performance. He used to argue a lot with troupes’ directors as well as with his partners, so they had to find a replacement. His works were part of the open collective heritage during this period, i.e. everyone had the right to sing Ḥigāzī’s qaṣā’id their way and without his permission. Exactly as ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s, ‘Uthmān’s, Dāwūd Ḥusnī’s, Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī’s melodies were interpreted.

Copyright did not exist yet.

Copyright appeared with the record companies.

The big difference between the adwār of the waṣla and Ḥigāzī’s qaṣā’id resides in the fact that those who sang Al-Ḥāmūlī’s adwār were muṭribīn who did not sanctify melody. They simply saw it as a canvas onto which the inventive and creative artist had to imprint his own personal style… because singing during the Nahḍa period had to be a novelty, not a repetition.

Those who re-recorded the works of Salāma Ḥigāzī:

Professional muṭribīn including Munīra al-Mahdiyya –who recorded with Baidaphon, as mentioned earlier, 8 of Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s qaṣā’id between 1820 and 1923–, Muṣṭafa Amīn, Aḥmad al-Shāmī, Zakī Murād, and Aḥmad al-Mīr in the Levant;

Or actors with beautiful voices such as the ‘Ukāsha brothers, who were working within the frame of an art still new in the Orient, and may have felt that respecting the melody was essential to the performance of the pieces… because every actor had the obligation to serve the melody, while the muṭrib used it for ṭarab purposes as well as to demonstrate his creative ability. Thus we can affirm that the Sheikh had clever imitators, but no disciples.

Yes

Of course.

We must listen now to excerpts from Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s works sang by others.

What do you propose?

“In kuntu fī al-gaysh” for example, sang by Munīra al-Mahdiyya.

The difference between “In kuntu fī al-gaysh” sang by Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī and the version of Munīra al-Mahdiyya is obvious:

First, Munīra al-Mahdiyya’s version is shorter and includes fewer verses. Also, she focused a lot on “Yā man tamallaktumu qalbī” and concluded to the nahawand instead of continuing to the bayyātī and the sīkāh tīk ḥisār like Sheikh Salāma. She concluded almost on the second side of Sheikh Salāma’s record, followed by taqāsīm to Ibrāhīm Sahlūn’s kamān and ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī’s qānūn. Which implies a shorter version of “In kuntu fī al-gaysh”.

There was another imitator of Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī –in a different way– who merged both qaṣā’id “In kuntu fī al-gaysh” and “Salāmun ‘ala ḥusnin”. (We had promised you in a previous episode to re-discuss these two qaṣā’id). This imitator is Aḥmad Fahmī al-Fār who recorded 3 years after Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s 1905 recording. Fihmī recorded in 1908 what we are listening to now, a very short record side of 3 minutes. Funnily, the album carries the label “The story of Romeo and Juliet”.

With all due respect to operettas and to what Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī brought to them, let us go back to Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī, the great muṭrib and performer outside operettas… in adwār for example as well as in qaṣā’id ‘ala al-waḥda at which he equalled his contemporaries.

I truly consider Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī as a genius performer of adwār in every aspect. Unfortunately, he only recorded eight or ten of those. Let us try to categorize the muṭribīn into two units:

1- The unit of Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī where the muṭrib imprints the dawr with his personality while respecting the melody, i.e. adds variations to the melody without retrieving or cancelling anything.

2- The unit represented by ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī where the creative artist freely keeps only what pleases him from the composed dawr, on the spur of the moment.

So, any recording of a dawr made by ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī is different in essence from another recording made with another record company.

On the other hand, with Al-Manyalāwī for example, there is a general idea and a specific structure of the dawr.

Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī should be categorized within Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī’s unit, because the adwār he sang followed a “Ḥigāzī” structure.

He must certainly be of this school since he composed adwār himself.

He was indeed a composer of adwār, which may have led him to respect the will of composers then to add his own variations and ornamentations. A good example is Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s genius performance of dawr “Qaduh el-mayyās zawwid wagdī”.

Great.

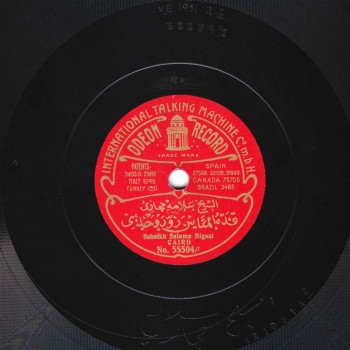

Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s second characteristic in the performance of adwār is dancing and his dancing spirit. For unclear technical reasons –you may know about those more than I do–, the sound of the percussions is a little more apparent in the Odeon records than it is in the Gramophone records.

Gramophone… strange. Yes, it is true. In ‘Abd al-Ḥayy’s recordings including percussions, the latter are apparent enough. Whereas in Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s recordings, either the percussions are very apparent, or there are no percussions to begin with.

Exactly. And particularly in the performance of “Qaduh el-mayyās zawwid wagdī”, it seems that Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī actually meant to adorn this dawr with ecstasy and joy. Joyful dancing made it unique, unmatched. When listening to this dawr, we also clearly notice the great work between the muṭrib and the madhhabjiyya as well as the undoubtedly prepared shiftings, i.e. “Qaduh el-mayyās zawwid wagdī” surely included a pre-composed improvised part.

Let us listen to dawr “Qaduh el-Mayyās” that he did not sing with the habitual Odeon band. He sang it accompanied only by Ibrāhīm Afandī Sahlūn’s kamān, Muḥammad Afandī Ibrāhīm’s qānūn, and a percussionist whose name we do not know.

Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s contemporaries sang his adwār. I think that Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī –who was older than Ḥigāzī–sang his dawr “Li-ghēr luṭfak”.

It does take a muṭrib of Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī’s caliber to sing a dawr composed by Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī who was maybe considered as his competitor. Al-Manyalāwī singing a dawr by Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī is undoubtedly a mark of reverence and honouring for this man’s genius. Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī deemed that Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī –even if he were an impersonator– was worthy of having him (i.e. Al-Manyalāwī) sing his adwār.

Isn’t it so?

Al-Manyalāwī’s family says that Sheikh Yūsuf kept all Salāma Ḥigāzī’s records –those existing at his time of course.

Let us summarize and conclude our discussion about Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī.

Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī was two muṭribīn in one:

On one hand, Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī the genius takht muṭrib and performer of adwār who imposed his personality on the adwār with inventiveness and artistic spirit as strong as the spirit of ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī or Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī –even if we have placed him within Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī’s category considering his respect for the melody. The respect –not imitation– coupled with adding personal inventions/variations to the pre-composed melody.

On the other hand, Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī the father of a unique experience who attempted to tame ṭarab and use it for drama purposes, far from western expressionism. Whether he succeeded or failed in this attempt, I do not know. But at least he paved the way… a path no one else took. All those who followed Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī based their work on his experimental melodies instead of adopting the core of Salāma Ḥigāzī’s musical concept: the attempt to enrol, develop, and normalize ṭarab and cantillation within a drama frame.

Can we conclude the episode with a question?

Go ahead.

Can we consider Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī as the starting point of the “schizophrenia” of development from inside out?

This is a strong word, yet I am afraid it is appropriate.

We thank Professor Frédéric Lagrange.

We will meet again in a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh” to discuss another historical figure or historical event.

“Min al-Tārīkh” is brought to you by Muṣṭafa Sa‘īd.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)