The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

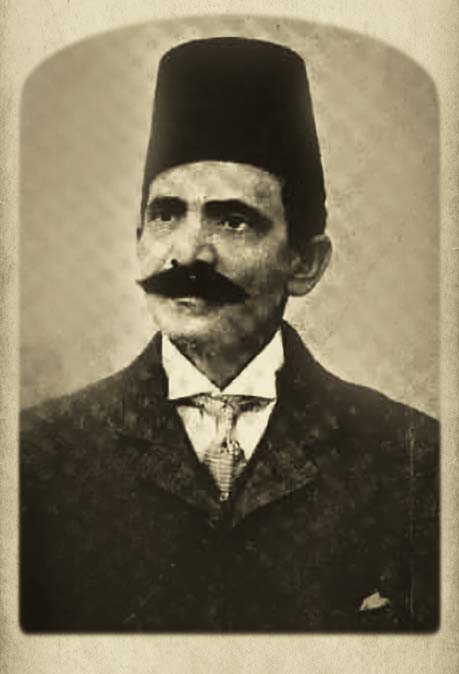

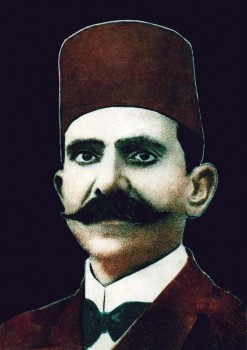

In today’s episode, we will resume our discussion about Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī.

Tell us about Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s journey after he left Beirut’s port where he was asked to sing qaṣīda “In kuntu fī al-gaysh” so the public would allow him to aboard the ship.

After Beirut, Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī went to Damascus in 1909 where he unfortunately suffered his first hemiplegic attack that seemingly did not affect his vocal abilities. … But just try to imagine half paralyzed Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī leaning over Juliet’s body in the play… a pretty funny scene indeed.

Was his hemiplegic attack caused by anything?

I honestly do not know.

Did he remain hemiplegic until he died, or was he cured?

He was not cured. He remained hemiplegic to his death.

And he went on acting despite his illness…

He continued acting, with a crutch. He resumed his theatre activity in 1911 and produced new plays, in collaboration with the ‘Ukāsha brothers or with actor George Abyaḍ. Even tired, he travelled to Tunisia in 1914. I think he is the first Egyptian muṭrib ever to travel towards the Arabic Maghrib.

Did this mark the beginning of a journey between Egypt and Tunisia, …with a lot of…?

Of course… it was the beginning of the movement including Sayyid Shaṭā…

Amīn Ḥasanayn Sālim, and even Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb.

Truly!

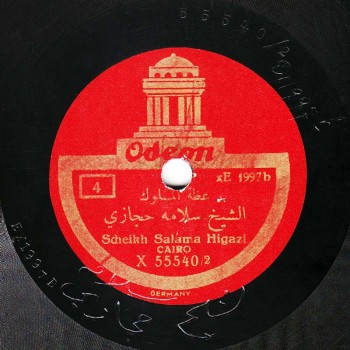

He travelled to Tunisia in 1914 where he exhausted his energy. Note that along with his illness he also suffered from serious financial problems. We can’t say that he died poor, but his financial situation was not at its best when he died in 1917. Unfortunately, he was not able to record anything because of the monopoly agreement he had signed with Odeon.

It is important to talk about Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s music methodology. The same as with other muṭribīn’s works, we are only acquainted with Salāma Ḥigāzī’s art through his discs. We do not know to what extent these recordings can be trusted as true representatives of the musical art, or to what extent they distort or change what people actually heard in concerts or on the theatre stage. Anyway, if we want to get acquainted with Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s works, the only medium we have are these 78LPs. Those who imitated Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī in their recordings include first and foremost Sitt Munīra al-Mahdiyya.

His pupil.

His pupil, of course.

And ‘Abd al-Wahāb.

And ‘Abd al-Wahāb… “Ataytu fa-alfaytuhā sāhira”.

And “Wa mā ḥīlatī”… these are his first two recordings, aren’t they?

Yes they are.

And Zakī Murād.

Fortunately, some muṭribāt can be considered more as ‘awālim than muṭribāt, such as Na‘īma al-Maṣriyya who recorded works by Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī that he did not record in his own voice.

Damascene muṭribīn recorded works by Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī?

Sure, especially that he was very famous in the Levant. Still, all we have now are of course his 78LPs.

Whose number does not exceed 48. That is not a lot compared to other muṭribīn.

Yes, this is a very little number compared to ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī or Sayyid al-Ṣaftī ‘s recordings for example. But there is a difference between them: Sayyid al-Ṣaftī or ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī recorded with almost all the records companies, not leaving any of them out. Whereas, unfortunately for us, Salāma Ḥigāzī only recorded with Odeon. He could not record with any other company. Out of the 48 discs we have, 23 are in fact musical pieces excerpted from his theatre works. The rest are qaṣā’id ‘ala al-waḥda, adwār, and maybe a few salāmāt. We do not know for sure if he performed them on the theatre stage, but they were most probably part of his plays. Strangely enough, he did not record mawāwīl.

Very strange indeed.

He clearly sang mawāwīl in his concerts, but for an unknown reason he never recorded any.

The record companies were interested in his theatre works more than… He was indeed more dedicated to those than to his work as a good muṭrib.

Of course.

Also, qaṣā’id mursala replaced the mawwāl to a certain limit (their form is almost the same as the mawwāl’s but their text is written in literary Arabic). Most theater recordings are of qaṣā’id mursala (of non-metric measure). They are long –sometimes very long– qaṣā’id requiring 3 or 4 sides, such as “In kuntu fī al-gaysh”, “Salī el-nugūm yā Charlotte”, and “Salāmun ‘ala ḥusnin”. I remember that the Latin transcription on the last qaṣīda’s album is “Salāmun ‘ala Ḥasan” instead of “Salāmun ‘ala ḥusnin”. It looks like the concerned party did not understand the meaning of “Salāmun ‘ala ḥusnin”. There is also qaṣīda “Mātat shahīdata ḥubbin”..etc. We have to listen to some excerpts of this marvellous qaṣīda mursala.

“Mātat shahīdata ḥubbin” (she died, a martyr of love)?

For example.

Then let us listen to “Mātat shahīdata ḥubbin”.

Now concerning the long qaṣā’id. They are constituted of approximately 15 verses. Their recorded performance lasts around 15 minutes. So, their live performance probably lasted at least 20 or 30 minutes, especially when the audience was eager for repetitions. These works enchanted the listeners and showcased repetitions as well as vocal ornamentations and brave leaps –sometimes acrobatic or prowess-like–, and shiftings from higher octave notes to lower octave notes.

Very sudden drops indeed.

Very sudden drops constituting very powerful dramatic articulations that Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī used a lot, and that were also used by muqri’īn (Kuran reciters) after him or maybe during the same period. It is of course a trick, if we may call it so, ‘Abd al-Bāsiṭ ‘Abd al-Ṣamad was famous for.

For example.

Some maqām shiftings in these qaṣā’id are closer to the art of a muqri’ (Kuran reciter) than to the art of a muṭrib, i.e. there is an obvious difference between the performance of a qaṣīda by Al-Manyalāwī and the performance of a qaṣīda mursala by Salāma Ḥigāzī. The free shiftings of Salāma Ḥigāzī led him to forget about going back to the original maqām. As if his was an independent art outside the rules and norms of performance of the qaṣīda mursala by takht muṭribīn, even though he was himself a takht muṭrib. Theatre art is closer to cantillation. Note that the dramatic tension is created by these maqām shiftings. When Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī attempted expressionism and figurative interpretation following the western style, more precisely following the Italian and the French styles, it was impossible to determine the proportion of improvisation and the proportion of composed melody in these works. They often sound like cantillations, i.e. when listening to qaṣā’id such as “In kuntu fī al-gaysh”: was it actually possible for Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī to repeat the exact same melodic pattern every time? Of course, when Munīra al-Mahdiyya recorded this qaṣīda, she recited it exactly like Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī. But was she imitating him in his concerts or in his recording? In my opinion, she imitated the recording and not Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī.

Most probably… I doubt that a person such as Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī had the ability to memorize this amount of mursala melodies.

Exactly.

I doubt it very much. It would have been too difficult for him to memorize his performance. He could not have memorized the same mursala melody even if he wanted to.

He may have memorized some shiftings.

For drama purposes, it is possible.

Exactly, just for drama purposes. In these recordings, he is accompanied by a qānūn playing solo –or that seems to be playing solo–, since we can sometimes hear the other takht intruments at the beginning of the record side, or at the end of the record. Yet, during the performance, we usually only hear what resembles a reduced takht or solo qānūn playing.

The written memoirs of one of Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s contemporaries state that he used to chant the qaṣā’id on stage during a play without the takht, i.e. completely solo without any instrumental accompaniment. Is this true?

Of course it is. We know for example that Umm Kulthūm recorded with the takht before presenting her songs in concerts with the takht. In her first concerts in the early 1920s, she was accompanied by a biṭāna of mashāyikh, while during the same period she was recording her discs with the takht. Thus, Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī possibly sang completely solo on the theatre stage while recording these musical pieces with Odeon with the takht.

Anyway, he left us a trace of a recording without a takht. Only one, but it exists.

Of course, it is the elegy composed for Muṣṭafa Kāmil Bāsha, one of Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s marvels.

On two records.

Beautiful!

As if he were wailing.

“Al-mashriqān ‘alayka yantaḥibān”

Let us listen to Muṣṭafa Kāmil’s qaṣīda “Al-mashriqān ‘alayka yantaḥibān” written by the Prince of Poets Aḥmad Shawqī Bēk and recorded on four 27cm record sides.

What do you think about the piece we just listened to? Isn’t it strange that his performance of this work is different from that of his other works?

It is obvious.

As if he were truly sad.

When listening to this disc, we directly notice the link between Kuran reciting, chanting, and singing.

Of course, he does sound like he is cantillating in some parts.

Cantillation, truly. It seems that all these qaṣā’id are a copy of traditional chanting and cantillation, from the Mosque, from Sufi ceremonies to the theatre stage. And it seems that this traditional art was used to express literary issues –which is very far from the habitual Sufi ghazal– to express dramatic situations. So this attempt remained unique and alone. The question roaming the minds of educated people during this period was: are maqām music, the takht, or cantillation adequate for expressing something besides the anguish of love? Is it possible to “Egyptianize” singing theatre art whether it is named “Opera” or “Operetta”? It seems that Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s attempt did not convince all his contemporaries. For example: I can almost affirm that there is an echo of the protests caused by Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī in the book “Ḥadīth ‘īsa bin Ḥishām” written by Al-Muwayliḥī. Of course, Al-Muwayliḥī is considered as one of the revisionists and very open-minded intellectuals in the late 1800s and early 20th century.

Which protests are you referring to, Sir?

In his book “Ḥadīth ‘īsa bin Ḥishām”, Al-Muwayliḥī criticized actors very harshly. And I think that his critics were aimed at Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī even though he did not mention him by name. Al-Muwayliḥī ridiculed those mashāyikh who wailed on stage, played the role of Islamic heroes, and cantillated melodies resembling Kuranic cantillation while acting in front of an audience. I mean… can these words be aimed at someone else than Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī? I do not think so.

Sure, but did he offer a solution?

He only criticized.

Some books mention a specific qaṣīda and a specific tune… for example Kāmil al-Khula’ī’s book when he tells about Salāma Ḥigāzī. Some of these melodies were recorded on discs, weren’t they?

Salāma Ḥigāzī authored theatre “compositions” besides the long qaṣā’id mursala, referred to in Kāmil al-Khula’ī’s book as “melodies”. For example: the “ ‘ā’ida” story included seven qaṣā’id mursala and seven melodies. The poem’s text or the mention of the maqām and the rhythm in the book by Muḥammad Fāḍil clarify the fact that these melodies were played like muwashshaḥāt, i.e. a collective singing and a fixed melody onto which the muṭrib embroiders some improvised phrases. Ḥigāzī undoubtedly copied this manner from Abī Khalīl al-Qabbānī. Unfortunately, Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī only recorded a few of these melodies, including: “Laḥn al-quḍāh”, “Laḥn al-mawt”, and “Laḥn al-ḥayāt”.

On one disc?

On one disc where each melody sounds different from all the other tunes composed by Ḥigāzī. These three pieces are composed to maqāmāt that can be played on medium-sized instruments. These maqāmāt are: ‘ajam and nahawand. Also note that the last melody is a “mazurka”. In these recordings, the Sheikh is accompanied by a type of band of at least 10 musicians, not by the takht.

A few string instruments such as those used by western orchestras for chamber music.

Note that these melodies are chanted by a group closer to a chorus than to a biṭāna of madhhabjiyya. Salāma Ḥigāzī recorded a lot of his performed ornamentations. He also inserted within the melodic pattern passing signals to maqāmāt with Arabic tendencies, and the band was unable to accompany him when he performed those.

In fact, even the biṭāna does not sing to notes with a western tendency. They sing neither Major nor Minor. They sing as if to the ‘ushshāq or to the jahārkāh.

True.

Anyway, in my opinion, this recording is very confusing: it goes against the ornamentations Salāma Ḥigāzī had adopted in his other compositions. This was undoubtedly a unique “expressionist” attempt that perhaps inspired Ḥigāzī’s followers including play composers such as Dāwūd Ḥusnī, Sayyid Darwīsh, ‘Abd al-Wahāb, and Kāmil al-Khula‘ī. Salāma Ḥigāzī undoubtedly gave this attempt great importance. A fact highlighted in a rare anecdote told by Muḥammad Fāḍil in his book: Ḥigāzī criticized his competitors because of their inability to “express” what he was convinced he had demonstrated in his melodies. For example, one day in 1916, Munīra al-Mahdiyya went to him complaining about Kāmil al-Khula‘ī’s composing for “Carmen”, saying the “ ‘asākir” (soldiers) tune was totally devoid of the required stamina. Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī responded: “Because his soldiers are a product of recycling”.

He told Munīra.

Yes.

In my opinion, Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s genius is not limited to such an experimental attempt. This reminds me a lot of Sāmī al-Shawwā’s attempts in the 1920s when he recorded “Taḥnīn al-walad” or something like that… yes, “Taḥnīn al-walad” for example. Yet Sāmī al-Shawwā’s genius is not limited to “Taḥnīn al-walad”, it resides in his ordinary taqāsīm. The same goes for Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī… This is only my personal opinion.

Anyway, we do not know what used to take place on stage.

Exactly.

In the early 20th century, these melodies were undoubtedly very modernistic, and surely elicited enthusiasm and admiration. Still, it is impossible to hide from contemporary listeners their low artistic value compared to the long qaṣā’id mursala. What the public expected from Salāma Ḥigāzī, and what the Sheikh succeeded in demonstrating, is ṭarab’s high dramatic value and power to express.

Well spoken, Sir.

Anyhow, we have reached the end of today’s episode on Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī.

We will meet again in a new episode resuming our discussion, where we will talk about Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s imitators as well as about other aspects of Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s art.

“Min al-Tārīkh” is brought to you by Muṣṭafa Sa‘īd.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)