The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Today, we will be discussing the singing of the ‘ālima. This term came to imply different meanings throughout time. The ‘ālima are a world by itself, with different ranks and various types according to the country and the period.

Prof. Frédéric Lagrange will be telling us about them today.

Let us start with the meaning of the term ‘ālima. I think the pre-conceived idea about the concept of ‘ālima was formed from the following movies: those of Ḥasan al-Imām in the 1960’s, “Shafīqa al-Qubṭiyya”, Nagīb Maḥfūz’s trilogy, and “Sulṭānat al-ṭarab”…etc… to such an extent that if we adjoined today a fine quality to the word ‘ālima, we would feel that there is a contradiction, that both words cancel each other. Whereas the situation was different in the 19th century where the term ‘ālima implied its original meaning, i.e. an expert in the affairs of singing. The term ‘ālima sometimes implies a muṭriba, or mughanniya. There was indeed a ranking order amongst ‘ālima: Almaẓ and Sākina were both ‘ālima, yet a world of difference separates Almaẓ from Sākina and from the ghāziya (female dancer). The line between a ‘ālima and a ghāziya is sometimes unclear, i.e. 3rd and 4th rank ‘ālima sang and danced, they were at once ‘ālima and ghāziya, while 1st rank ‘ālima sang at the Khedive’s court. Hence, ‘ālima may imply either “fine” female singers, or those who performed in baladī and mountain weddings.

Does the term ‘ālima also imply an expert in the affairs of women?

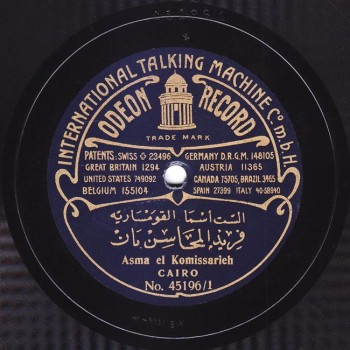

They could indeed be experts in the affairs of women as well as experts in the affairs of singing: baladī‘ālima who perform in weddings and sing exclusively for women may give valuable advice to brides, issues mothers or higher class women are ashamed to discuss. Of course ‘ālima, often unreserved, will go straight to the point and explain what is going to happen. They are experts in both the affairs of women and those of singing. We must make a distinction between the different ‘ālima ranks. First, the 1st rank ‘ālima: those who sing the male repertoire… to whom do they sing it? We obviously can’t give a definite answer to this question. Almaẓ, for example, sang for both women and men… did she perform in front of men or did she sing behind a curtain so they would not see her? Some ‘ālima used to hide from men’s eyes to protect their virtue, and sing behind a veil or a curtain, or on other occasions sing exclusively for women. Sākina, for example, also sang for both men and women. Maybe men spied on what was happening in the “haremlik”, maybe they chose for a famous ‘ālima to sing at a certain time so everybody could listen to her. Then comes the muṭrib who sang either after or before the ‘ālima… they sometimes sang at the same time. There is a pleasant anecdote in Qasṭandī Rizq’s book I think, concerning the fierce competitive battle that took place between Almaẓ and ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī: Almaẓ was trying to affirm her talent by singing louder than ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī, and the latter told her “Dear lady, is anyone denying your voice?”… They ended up getting married. This anecdote has a historical implication as it confirms that they were singing at the same time, i.e. he sang for the male audience while she sang for the female audience. The wedding organizer should have known better than to have them sing at the same time: he should have let them sing separately. Let us go back to the subject of 1st rank ‘ālima who used to sing also dawr and maybe qaṣīda. There is a question the discs can’t unfortunately help to answer: was their takht a female takht or a male takht? In fact, the recordings of 1st rank ‘ālima who sang dawr shows that the takht was undoubtedly a male takht. But does this reflect the reality of the music scene? Were there women who could play the qānūn, for example? There were women who could play the ‘ūd like Bamba the lute player who recorded several discs, and thus proves that there were female lute players. But we have not heard of a woman who played the qānūn before the 20th century. Also, were there any female nāy players, female kamān players, etc…? We have no information whatsoever on this. So, did they resort to male instrumentalists in some of their performances? We can’t possibly give a definite answer to this question. Yet we can say that the recordings made in 1905, 1906, and 1907 of 1st rank ‘ālima such as Amīna al-‘Irāqiyya, Bamba the lute player, and Asma al-Kumthariyya show that they sometimes sang accompanied by a male takht. Of course, the talent of these women artists in their performance of dawr was no less than the talent and genius of, I will not say 1st rank male artists such as Al-Manyalāwī and ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī… well, in my opinion someone like Asma al-Kumthariyya in her performance of dawr, is as good as Muḥammad al-Sab‘ or ‘Alī ‘Abd al-Bārī, or even better… she may even have actually surpassed them in some performances.

Let us listen a little to Asma al-Kumthariyya

Let us listen to Sitt Asma al-Kumthariyya

(♩)

Contemporary listeners might be surprised at how we still, today, accept the voices of the period’s male singers… Well I do not think anyone can deny the beauty of the voice of ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī, Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī, or Salāma Ḥigāzī. We do admit Asma al-Kumthariyya’s talent, yet her voice may disturb: the voices of this period’s female singers are not easily acceptable to the contemporary listener, right? Do you agree, or do you like their voices?

Personally, I do not have a problem with their voices… The voice is different, and the way they perform is also relatively different. It is acceptable… or one may get used to it after a while.

Exactly, people get used to it after a while. To my opinion, Umm Kulthūm represents a new phase regarding women’s voices, and we are used today to voices belonging to Umm Kulthūm’s generation.

Men’s voices have also changed.

Their voices have changed but still, we like the old ones’ voices that are easy to love. Whereas the voices of the period’s female singers are a little heavier to the ear in the beginning… yet one does get used to them after a while.

The chasm may often be bigger… Now regarding singing techniques, talent, and creative and maqāmī imagination during the performance, Asma al-Kumthariyya and Bamba the lute player are surely among the great muṭriba, as their performance reached the peak of art. The muṭriba ‘ālima type, i.e. when the term ‘ālima indicates a muṭriba, is followed by the ‘ālima who sing wedding ṭaqṭūqa that sometimes include indecent lyrics. Usually, they explain to the bride how to “negotiate” her body in front of the groom, i.e. how women should behave in order for their husband to value them in the future. These ṭaqṭūqa belong to a vastly shared repertoire between Egypt and the Levant. These ‘ālima travelled from Cairo, to Beirut, to Damascus, to Aleppo and back to Cairo. The Damascene ‘ālima also travelled to Cairo and took some Egyptian ṭaqṭūqa, transformed Aleppan qadd into Egyptian ṭaqṭūqa and the other way around. The repertoire is often a shared one, and many Syrian-Lebanese tunes are included in the early century Egyptian –or Egyptianized– ‘ālima’s songs. Some of them are famous muṭriba like Sitt Bahiyya al-Maḥallawiyya or debutant Munīra al-Mahdiyya in the first phase of her career. Bahiyya al-Maḥallawiyya’s records are light, pleasant and funny, and often start with “Allāh Allāh, the famous Sitt Bahiyya al-Maḥallawiyya, my darling!” followed by “Yā Sī Tawfīq”. Did anybody find out who Sī Tawfīq is?

I do not know. But since he is not one of the three well-known Odeon takht members…

Then he is probably the one holding the castanets.

“Allāh Allāh Yā Sī Tawfīq”… Let us listen to this!

Let us play this!

(♩) (Bahiyya al-Maḥallawiyya “Itmakhṭarī yā ḥilwa yā zēna”)

Ṭaqṭūqa whose lyrics describe how a woman should “negotiate” her body in front of her husband include “Bi-sitta riyāl”, “Khallīk ‘ala ‘ōmī yā mōg el-baḥr”, and “Yā nakhlitēn fī el-‘alālī”. Note that all muṭrib kept from singing this type of songs except for ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī.

Let us listen to a short excerpt of him singing “Amara yā amara yā ammūra” (“Qamara yā Qammūra” / “Moon, little moon”) that contains obscene lyrics.

Yes, a little.

But it is cute indecency.

Of course, of course, for sure.

(♩) (‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī “Amara yā ammūra”).

The articles of the early 20th century’s Egyptian media, for example the early 1920’s’, show the conservatives’ repeated objections regarding the lyrics sang by these women in their recordings: they protested, shocked at having pure innocent young girls listen to such immoral words in their homes. They demanded censorship over art products, to such an extent that one of the great immoral lyricists, Sheikh Yūnis al-Qādī, was put in charge of censorship even though he had been the first one to write these indecent lyrics. We would love to hear another sample of ‘ālima’s singing. Besides Bahiyya al-Maḥallawiyya, there was also Munīra al-Mahdiyya…

Let us listen to Sitt Munīra in the bloom of youth around 1906, when she recorded with all the record companies. She is performing a very famous wedding song at the time, ṭaqṭūqa “Yā lamūnī” recorded by Odeon.

We will end the first one of our episodes dedicated to the singing of the ‘ālima with this recording of Munīra al-Mahdiyya.

We will meet you again in our next episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)