The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Today, we will be resuming our discussion about the singing of the ‘ālima with Prof. Frédéric Lagrange.

Sir, is there another type to the ‘ālima’s singing besides these two urban types/ranks? Some sing dawr and others sing ṭaqṭūqa, yet there isn’t a big difference between them since they share many characteristics. Is there a third type?

There is a third rank: the baladī ‘ālima who almost made no recordings. There is a rare disc –I know you like it very much– of Bahiyya al-Maḥallawiyya imitating Folk ‘ālima. Let us listen to her a little.

Ok.

(♩) (“Faraḥ el-fallāḥīn” by Bahiyya al-Maḥallawiyya, recorded by Odeon, order # 45006).

Besides Bahiyya al-Maḥallawiyya’s recording where she imitates Folk ‘ālima, I think the only other recorded sample of these baladī ‘ālima is Annūsa al-Maṣriyya’s Cairo Congress recording. Note the great chasm between Bahiyya al-Maḥallawiyya and Annūsa al-Maṣriyya: they seem to belong to two completely different types of performers. Actually, they belong to totally different classes of ‘ālima. Shall we listen to Annūsa al-Maṣriyya in the Congress?

Let us listen to Sitt Annūsa al-Maṣriyya.

(♩) (“Yā ṭal‘it el-badr el-munīr”)

Also, a number of muṭriba who became famous at that time as first rank muṭriba such as Amīna al-‘Irāqiyya apparently started off like Annūsa al-Maṣriyya. Some of them performed more baladī type songs. Let us listen to Sayyida Amīna singing “Zār”.

Great! Concerning “Zār”, the ‘ālima Na‘īma al-Maṣriyya who became a singer or muṭriba in the 1920’s was also a “qūdyit zār”.

They say that she continued being a “qūdyit zār” after she stopped singing,

She was right to do that.

Explain to us what “qūdyit zār” means before we listen to Sitt Amīna singing “Zār”.

A “qūdiyit zār” conducts the zār. It is a ceremony close to an exorcism ceremony, i.e. meant to expel demons or to calm them down.

Then let us expel the demons.

(♩) (“El-Zār” performed by Amīna al-‘Irāqiyya, recorded by Baidaphon, order # 34999).

What are the sources we can rely on to learn the truth about ‘ālima? Are ‘ālima like those described by Nagīb Maḥfūz in his trilogy, especially El-sulṭāna in “Aṣr el-Shō’ ”? Or like those described by Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm in the story “ El-‘awālim fī al-qiṭār” (“The ‘ālima in the train”) and in his famous story “ ‘Awdat el-rūḥ” (“The return of the spirit”)? Reading these two sources carefully will unveil a totally different image of ‘ālima. Nagīb Maḥfūz’ ‘ālima are closer to courtesans (excuse my language), i.e. low-class muṭriba. As an example, there is a beautiful and pleasant scene in “Aṣr el-Shō’ ” where Sayyid Aḥmad ‘Abd al-Jawwād asks El-sulṭāna not to sing anything but ṭaqṭūqa because he can’t stand listening to women who dare to perform serious songs, as he considers them unworthy of this type of works and of such marvellous pieces. Hence, he would only listen to dawr performed by Sī ‘Abduh or by Sheikh Yūsuf, not by a ‘ālima whom he judges to be incapable and unworthy of performing such works. Those were Nagīb Maḥfūz’ ‘ālima, whereas Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm’s ‘ālima in “ ‘Awdat el-rūḥ” are a different species altogether, even if the lead-‘ālima’s name is “El-sitt Shakhla‘ ” (Lady Playful), a name that obviously implies that she sings “playfully”. But what does she sing? There is a fantastic funny scene in “ ‘Awdat el-rūḥ” relating a Jewish wedding: at the beginning of the century, Jewish brides had to take a ritual cold shower. This wedding was taking place on a very cold winter day, and only another Jewish person could touch the bride or else she would have to endure this ritual cold shower again. Then ‘ālima Shakhla‘ came along and touched her to feel the fabric of her dress, and the bride whose teeth were chattering had to shower again. Of course, everybody stayed angry with the ‘ālima until everything went back to normal. Then, because of all the disturbance and trouble during the wedding, Sitt Shakhla‘ started singing off-key, and a member of her takht told her “Yā nashāz kār, yā nashāz kār” (“Off-key kār, off-key kār”), trying to convey to her through a technical term that she was singing off-key. Consequently, Sitt Shakhla‘ chose to sing ṭaqṭūqa… So, what was she singing before that? Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm doesn’t say. He only cites “Kēd el-‘awādhil kāyidnī, kēd el-‘awādhil kāyidnī”. Those who know about dawr will understand right away… moreover, he added “Mā tṣallaḥī el-‘ūd hijāz kār” (Won’t you tune the ‘ūd to the hijāz kār?) making it clear that the ‘ālima was performing “Yā ma-inta waḥishnī”, i.e. one of the hardest dawr. When she realised that she was unable to continue performing it since she was singing off-key because of all the earlier trouble, she shifted to the easy and light ṭaqṭūqa and told the members of the takht “the hell with them and with kēd el-‘adhūl!” Also, “ṣallaḥī el-‘ūd hijāz kār” (tune the ‘ūd to the hijāz kār) implies that she was knowledgeable in the art of maqām. I doubt Sitt Annūsa al-Maṣriyya knew about “hijāz kār” or about bayyātī.

Clearly. Yet it seems that others did. Lute player Bamba’s singing and playing show that she knew about maqām. Let us listen to her singing a pleasant dawr.

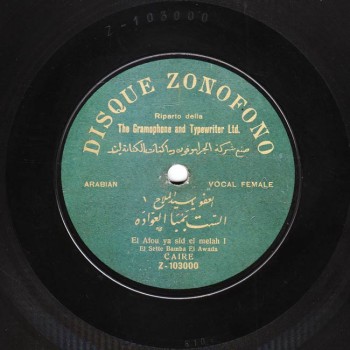

(♩) (“El-’afū yā sayyid el-milāḥ” recorded by Zonophone, order # Z-103000).

The ‘ālima may actually be an expert.

There is a short pleasant story by Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm “The story of the ‘ālima” / “Fī al-qiṭār” (“In the train”). There are ‘ālima in a train behaving as expected of ‘ālima. The main concept of the story is “conceitedness is a craft”: there are travellers in the train and it is the month of Ramadan. Everybody is fasting except for the ‘ālima who are smoking. Of course the “commissary” (train conductor) stares at them angrily because they are smoking and eating during Ramadan. They may have been religious, but let us remember that this was the early 20th century. The train conductor is looking at them angrily while the travellers, on the other hand, have guessed that they are ‘ālima who are not expected to behave otherwise. And since the travellers are fasting, they ask the ‘ālima to sing something for them.

They were clearly fasting.

They were… there is no contradiction between fasting and listening to the ‘ālima singing, is there? They insistently asked her to sing “Fī el-‘ish’i aḍḍēt”. I researched a lot until I found out it was Sitt Amīna al-‘Irāqiyya who recorded this song that is somewhere between a ṭaqṭūqa and a dawr… well, a ṭaqṭūqa including ṭarab.

Do we know who composed “Fī el-‘ish’ ”?

Unfortunately not. It is probably an old folkloric melody, or an old dawr whose composer is unknown… or maybe someone like Muḥammad ‘Alī Li‘ba.

By the way, it could very well be Muḥammad ‘Alī Li‘ba… someone told me that the original title of this ṭaqṭūqa is “Fī el-fisq” (fisq: debauchery).

Anyway, let us end the second one of our episodes dedicated to the singing of the ‘ālima with this ṭaqṭūqa.

We thank Prof. Frédéric Lagrange, and we will meet again in our next episode of “Durūb al-Nagham” to resume our discussion with him.

(♩) (“Fī el-fisq anā aḍḍēt ‘umrī”, Gramophone G.C.-3-13874).

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)