The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Today, we will be resuming our discussion about the singing of the ‘ālima with Prof. Frédéric Lagrange.

Sir, why did everybody end up with this wrong understanding of the word ‘ālima?

In the 20th century, the term ‘ālima started being used exclusively for baladī singers who entertained at weddings.

When did this turning point take place?

I think it happened around the first three decades of the 20th century: starting in 1922-1923, there were no “high-class” ‘ālima anymore. This is when these two words became opposites, which explains the difference between Nagīb Maḥfūz’ ‘ālima and Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm’s ‘ālima, since Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm was born in the late 19th century while Nagīb Maḥfūz was born in 1911… there is a 15 year’ difference between them.

Of course. Moreover, these 15 years are not like any ordinary 15 years.

These 15 years embody this change. Nagīb Maḥfūz’ ‘ālima is a woman of very questionable morality who sings indecent ṭaqṭūqa since the 1920’s ‘ālima, muṭriba and female singers used to entertain at weddings and to sing indecent ṭaqṭūqa. Whereas, to Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm who was born at the end of the 19th century, there was no conflict between singing dawr and being a ‘ālima. Moreover, record companies in the 1920’s either satisfied the demand of the audience or imposed to a great extent the love of ṭaqṭūqa. Old wedding ṭaqṭūqa were undoubtedly indecent, but this indecency was meant to inform the bride and to give her the tools to defend herself and to display her charms for her husband.

Do you mean that the ṭaqṭūqa were educational?

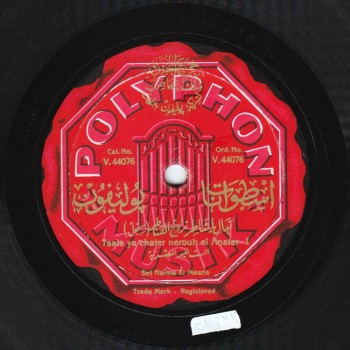

Exactly. They constituted an educational and useful indecency. While the indecency of the early and mid-1920’s lyrics is different because it was meant to make the audience laugh, to describe a certain class of “easy” women, or to entice desire. I neither refuse nor condemn the enticing of desire, I only mean to highlight that the indecency aimed at a totally different purpose than it did in 1905. Some of these frivolous ṭaqṭūqa were marvellous and very funny, like Munīra al-Mahdiyya’s “Mā tkhafshi ‘alayya d-anā waḥda sigūriyā”, or Na‘īma al-Maṣriyya’s “Ta‘āla yā shāṭir nirūḥ el-anāṭir”.

(♩)

Let us look at the ṭaqṭūqa “Ta‘āla yā shāṭir nirūḥ el-anāṭir” composed by Zakariyya Aḥmad. It is by the way one of the most beautiful works recorded by Na‘īma al-Maṣriyya because, in my opinion, the contradiction between the sad bayyātī melody and the indecent lyrics gives it a special flavour. This contradiction between the obvious sadness prevailing in the melody and the indecent lyrics gives the impression that this woman was forced to utter these words despite her beliefs. I feel this every time I listen to this ṭaqṭūqa, and I think it adds a special kind of beauty to the piece. I am not saying that Na‘īma al-Maṣriyya was forced to do this. I am talking about the character of the lost woman she is playing, who is singing an indecent song without conviction, and thus mixes the indecency with sadness and despair.

(♩)

Umm Kulthūm, at the beginning of her career, sang two pieces: “El-khalā‘a we-el dalā‘a madhhabī” and “Anā ‘ala kēfak”. Later on, she tried to stop these records from being sold… Of course, they can be found in all audio-libraries, but are not broadcast.

(♩)

The problem is that there were also men who sang these same ṭaqṭūqa.

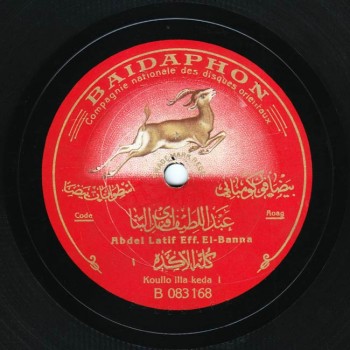

As for men, ‘Abd al-Laṭīf al-Bannā performed pieces from this repertoire throughout his career, along with the beautiful qaṣīda and the few dawr. He was the only muṭrib without a mustache –this detail is very significant to the experts–, and also sang most of his songs as a woman, pretending to be this playful girl. Let us listen to him.

(♩)

What about the role of ‘ālima in the nationalistic movement, i.e. the 1919 revolution? … All the women known as ‘ālima also sang ardent patriotic hymns…etc.

Exactly, especially Na‘īma al-Maṣriyya and 1st rank ‘ālima Munīra al-Mahdiyya on whose stage the wind of liberty blew. She recorded several ṭaqṭūqa whose lyrics sound innocent at first but are actually full of political insinuations, such as “Shāl el-ḥamām, ḥaṭṭ el-ḥamām” about the exile of Sa‘d Zaghlūl to the island of Malta, and Na‘īma al-Maṣriyya’s “Yā balaḥ Zaghlūl” whose lyrics are a praise to Sa‘d Bāshā Zaghlūl.

Shall we listen to “Yā balaḥ Zaghlūl”?

Let us listen to both.

Then let us listen to both.

(♩)

With these patriotic dawr performed by ‘ālima, we reach the end of today’s episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

We will meet again in a next episode with a new subject.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)