The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Today, we will discuss a popular singing style in the Arabian Gulf: baḥrī singing (baḥr = sea).

In this episode, we will talk about baḥrī work songs. The discussion will be conducted by Mr. Kamal Kassar and an expert on the subject, Mr. Ahmad al-Salihi.

Baḥrī singing is practised on the Gulf’s littoral, specifically between Kuwait and Qatar, passing through Bahrain, Al-Iḥsā’, and Saudi Arabia where the Dārīn region was, historically, one of the bastions of baḥrī singing.

Today, we will discuss Kuwait’s traditions essentially, knowing that 90% of those are also practised in the other regions.

Baḥrī singing is practised today in Kuwait by the young generation as well as by the 3 existing Kuwaiti baḥrī bands, though the latter’s members never went out at sea, and thus did not learn this fann out of necessity: they only practise it as a recreational fann or in order to preserve the old musical traditions.

With the discovery of oil, sea life stopped and consequently practising these fann was not a necessity anymore as they were intrinsically linked to sea work, whether on-board tasks or diving…etc. Consequently, it is practised today as a performance fann: the scenes are played in special venues in order to preserve these traditions.

The situation was very different in the past: fann baḥrī were inseparable from the sailors’ population of the region. This society had its own traditions and terminology, a specific way of life and social life. Marriage for example was limited within their social group. They knew each other, had their own way of communicating together, and had also built a relationship with the sailors’ populations of the other regions such as Saudi Arabia and Bahrain –that is if they were in Kuwait.

While working on the boats, these sailors sang because the tasks were very hard: singing helped them organize their work rhythmically and gave them the physical strength to conduct it. This exists in all work fields, and maybe all over the world.

Sea work also includes boatbuilding, doesn’t it?

It includes everything. There are 3 types of baḥrī songs:

- The work songs, each related to a specific task: raising the sails; rowing; carrying the merchandise.

- The recreational songs: the sailors did not work all the time. They took breaks and sang a different type of songs –not related to a specific task– that included dancing and clapping, and cheered them up.

- Special occasions songs: there are very few of those.

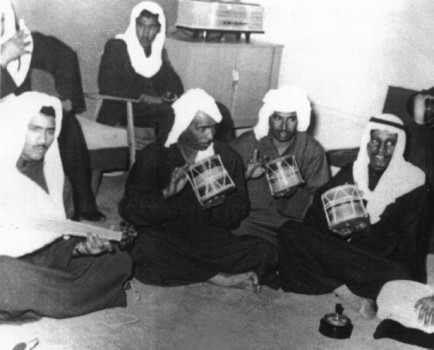

This fann consists majorly of work songs that are the most difficult because most require specific musical instruments: the ṭabl baḥrī –a big ṭabl covered with leather on both sides and played with both hands on both sides: the right side with a stick and the left side with the hand.

Is it held horizontally?

It is held horizontally with the strap on the player’s shoulder. The latter remains standing so he can move and dance with the rest. Most sea work includes two types of trips: the diving trip and the travel trip, the latter implying trade. This trade was conducted with India, Africa and Iraq (for the dates). They sang on these trade trips: they rowed, they raised the sails and lowered them, and they handled merchandise, taking it from Kuwait for example to Basra where they took the dates; then went for example to Africa where they took wood; then went to India where they took food; and finally went back to Kuwait. These operations required singing, i.e. the work songs, such as the shēla dedicated to carrying the dates: it is a simple song based on dancing, moving and a simple rhythm –mostly 6/8; and the kājūrī (that means dates in the Indian language) that they sang while carrying the dates in Basra.

This was one example related to one task.

The second task related to diving trips and travel trips included raising the sails and lowering them, added to pulling up the anchor.

There are tasks related to boats that go on both diving trips and travel trips. Each type has its own fann and rhythm as well as specific lyrics, dancing, moving, and interaction compatible with its style.

Will you play for us an example of each type?

This will be difficult because there are tens of them. Let us take a beautiful example called yāmāl.

What is it?

The yāmāl is a percussions-free mawwāl whose role is to keep the rhythm: a strange thing indeed because keeping the rhythm necessitates a ṭabl or another percussion instrument. Yet, when it comes to sailors and their very high and instinctive rhythmic sense and because of the circumstances, the mawwāl is the form that keeps the rhythm. Thus, the nahhām (sea muṭrib) sings a mawwāl called yāmāl. It starts with “Ōh yā māl”, followed by a qaṣīda called zuhayrī. The rowers pull to the right and to the left at the same time and with the same strength in order for the boat to move ahead in a straight line.

Some sailor told this old story about a boat that belonged to a Kuwaiti group who were not very experienced sailors. At sea, this boat went right and left because they did not know how to sail it. Of course, the sailors in the other boats laughed at them because of their weak instinct in organizing the rhythm inside their boat to keep it in trim. So, a year later, this Kuwaiti group brought in an excellent nahhām and paid him more money in order to recruit him. They did, and he helped them until they became the best and fastest boat of all. This famous story among old sailors highlights the importance of the nahhām as well as of the yāmāl.

Who will sing yāmāl for us now?

Who will sing yāmāl for us now?

Many performed yāmāl: all the nahhām performed yāmāl, including: Bahraini Sālim al-‘Allān, Aḥmad bū Ṭabaniya; from Dārīn in Saudi Arabia: Mubārak al-Rā‘ī; Kuwaiti Su‘ūd Ṣarām and Rāshid al-Jīmāz.

We will listen to one of them.

(♩)

I have mentioned that the percussions-free yāmāl fann is a mawwāl accompanied by the rowing movement and the humming of the sailors answering “Hēh” –implying “we are following you”– when the nahhām sang “Ōh yā māl”.

The other fann are accompanied by percussions. The work type songs, for example, sometimes start with a short mawwāl –most of which is a religious invocation to the Prophet or to God, as some of the sailors were scared because their work at sea can be frightening–; followed by muwaqqa‘ singing usually accompanied by a ṭabl and a ṭuwaysa that resembles the castanets played in Egypt and in the Levant, and of the same size. But, while castanets are played with one hand with two fingers facing each other, in Kuwait and the region, ṭuwaysa are played with both hands, each holding one of the ṭuwaysa’s plates, striking them against each other, and producing a sound close to the sound of a metronome, and thus keeping the rhythm and the dancing.

The second type, i.e. recreational singing, bears no relation with work singing.

First, its circumstances are old and mostly related to travel trips, not to diving that allowed no rest –besides sleeping– throughout its 4 months’ trip.

Whereas travel trips allowed rest since the boats visited the ports on their way: they would leave Kuwait for example and go to Dārīn, then from Dārīn to Bahrain, from Bahrain to Oman, then from Oman to Aden in Yemen, and from Aden either to Jeddah or to Tanzania. Thus, these trips included a two or three days’ break in every port where the sailors would spend the night on the boat and sing the evening away. In Kuwait, this is called “ins” from “Isti’nās” (companionship), and in Bahrain I think it is called “fijirī”.

This fann, in Kuwait, is called “baḥrī” as a musical form. In Bahrain and in Qatar, it is called “fijirī”…Two different appellations for the same fann.

The “event” itself is called “ins” in Kuwait: when the night came, they kept each other company.

On-board?

Yes. They would even invite the rest of the Kuwaiti, Bahraini, African, or other sailors to join them in singing baḥrī. Sometimes, there was a muṭrib –who played the ‘ūd– not a nahhām: so part of the “ins” was led by the jazwa (the sailors) and the other part by the mkabbis, i.e. the ‘ūd player and ṣawt muṭrib usually. Of course, ṣawt are not part of the baḥrī, yet are performed as a part of the ins.

Let us go back to work fann that are clear, defined, and easier, starting with the terminology and the sections of each fann or faṣl. Each faṣl in ins songs or recreational songs includes different sections. It always starts with the jrāḥān, an ordinary mawwāl with a specific style, technique, and specific traditions that includes a dialogue between the nahhām, i.e. the sea muṭrib, and the group.

At the end of the jrāḥān…

Does jrāḥān come from jirḥ (wound)?

That is possible, as the word “ijraḥ” (injure) is used to ask the nahhām to play the jrāḥān, a very sad singing type by the local population. The deep sadness of this fann is related to the hard work and the pain of being far from home because of this type of work. The jrāḥān, in specific traditions, is followed by the tanzīla, a collective song accompanied by percussions and free from clapping. After the tanzīla, the percussions continue in the same manner.

The rhythms are produced by numerous percussion instruments, aren’t they?

They are.

We have mentioned that work songs only require a ṭabl and a ṭuwaysa, unlike recreational songs that include various percussions. I will describe those after discussing the last part of the faṣl when the rhythms continue and the group stops singing and starts the naḥba i.e. humming, and the nahhām sings the nahma: another mawwāl different from the jrāḥān as to the tune, style, musical and rhythmic scale. The nahma is the peak of the work and always ends with “yā lēl yā lēl” that is the signal for the percussions to stop. The work itself, i.e. its musical as well as its recreational aspect, allows more than one nahhām to participate in every song. There are not enough nahhām today, so each fann is presented by one nahhām. In the past, one song could be sang by up to 3 or 4 nahhām, and lasted 30 to 45 minutes depending on the general mood. The percussion instruments used in recreational songs mostly included the ṭabl baḥrī and the ṭuwaysa, as well as the hāwin –used to crush garlic– and the water jug.

You mean the clay jug?

Exactly, an empty clay jug –that they drummed on to produce a bass sound– called īḥala, a taḥrīf (alteration) of ijḥala (jug). These percussion instruments were added to the mirwās known in ṣawt singing, and to clapping to a specific rhythm of a specific organized and very precise style.

When does the clapping take place?

The clapping takes place when the tanzīla (collective song) ends, and during the singing of the nahhām, i.e. the nahma –we listed earlier the jrāḥān, followed by the tanzīla, then the nahma– when they start clapping and dancing in an organized manner –unlike the faṣl’s first and second part in the jalsa that are random–: those clapping sit in circles during the nahma and drum on the floor with their hands a specific number of times –12 times, I think. Then they sit upright (they were drumming on the floor while on their knees). So they drummed on the floor and clapped their hands while the dancers performed inside or in between the circles. No definite anthropological study was conducted concerning these precise traditions and their specific symbols.

Could you play for us some examples of these sections?

Yes.

Let us play the jrāḥān for example.

Ok. We will play a specific part of the jrāḥān, followed by the collective song tanzīla, then the solo song nahma. All in all, the work is about 10 minutes’ long, while it used to last longer: after oil was discovered and this fann shifted from a work fann to a full-fledged recreational fann, the whole work became much shorter.

(♩)

In the 1960’s, Ḥamad Bin Ḥusayn, one of the first founders of bands in Kuwait, told his son Mr. Muhammad Bin Ḥusayn who is a friend of mine that fann baḥrī disappeared with the sailors’ disappearance, and that the so-called fann baḥrī played today is not up to the level.

Still, we are thankful that it is still practised by the young men who are keeping it alive. These very difficult fann necessitate precision and regular training, and keeping up with their many details is difficult without prior knowledge or training.

Dear listeners, we have reached the end of today’s episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

We will meet in a new episode to resume our discussion about the entertaining type of baḥrī singing.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)