The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Today, we will resume our discussion about baḥrī singing in the Arabian Gulf.

In this episode, we will talk about waṣlāt al-samar during the sailors’ breaks in ports or on special occasions…etc. During their breaks, the sailors organized samar evenings amongst themselves as well as with the other sailors who came from all over the world and were resting in the same port.

The discussion will be conducted by Mr. Kamal Kassar and an expert on the subject, Mr. Ahmad al-Salihi.

Let us first list the faṣl included in the ins:

- the ‘adsānī –the only faṣl that uses daff (that we call ṭārāt, or ṭāra, or ṭār);

- the mukhōlfī, or mukhālaf, or mukhawlaf;

- the ḥaddādī;

- the ḥasāwī…

Their percussions are the same, unlike their rhythm and their melody… but they are similar in general. Among these faṣl, the mukhōlfī is the only sardī (narrative) one, i.e. it does not include jrāḥān and thus consists of only two parts instead of three.

The ‘adsānī consists of three parts and includes the daff or ṭār percussion instrument.

Each fann has a specific characteristic.

Let us listen to a faṣl ḥasāwī that consists of three full parts: the mawwāl that is the jrāḥān; the collective song: tanzīla; the solo song: nahma.

Salman al-‘Ammari. He is a contemporary ṣawt muṭrib initially, but also one the best performers of baḥrī fann today. We will listen to him singing the three parts included in the ḥasāwī.

(♩)

Are these fann baḥrī recorded on tapes or on commercial discs?

As I mentioned earlier, these fann were practised in the past by sailors, i.e. the poorest community whether culturally or financially… a community of workers. They had an ethical value as men since they worked very hard, but their culture was basic. When they were asked if they had read about a certain issue, they would answer: “I can’t read, I am a sailor”. To them, being a sailor implied intrinsically that one was illiterate, with all due respect. To them, one could either read or be a sailor, never both at once… they said it themselves in old interviews.

Thus, there are no old recordings of this fann. They started with the appearance of radio stations, recording equipment, and television, i.e. starting the late 1950’s.

Unfortunately, diving had started to disappear since the 1930’s, and travel trips since the 1940’s. In Kuwait in 1951, no boats were going anymore either on diving trips or travel (trade) trips. So, those who recorded at first had left these fann for many years and thus did not give a 100% precise representation of the fann practised in the past. Moreover, many had died, and many had completely left these fann.

Still, we are fortunate enough that they were able to record a good collection that we are still learning from.

The old discs are very limited: fann baḥrī was first recorded in 1928 by Kuwaiti muṭrib ‘Abdallāh Faḍāla who recorded in Bagdad a collection of discs of different types of songs, including two baḥrī discs recorded by Baidaphon. The songs were played on the mirwās and accompanied by Ṣāliḥ al-Kuwaytī (violin) –who always played with him–, and by some Kuwaitis who were there and sang along with him, giving a simplified representation of baḥrī singing. Later during the recording era, this fann disappeared completely.

Do we have any of these two recordings?

I have a recording, not a disc.

Let us listen to an excerpt.

(♩)

Recording devices appeared in Bahrain and in Kuwait in the 1950’s.

In Bahrain, “Ibrahim-phone” recorded baḥrī singing performed by nahhām who were present there at the time, including Mubārak al-Rā‘ī from Dārīn in Saudi Arabia; Bahraini Aḥmad bū Ṭabaniya and Sālim al-‘Allān. They recorded a fair collection of discs –considered as late recordings because they were made after sea fann had disappeared.

While it was being recorded on discs in Bahrain, it was recorded on reels in Kuwait in 1952-1953 by baḥrī bands, including the Bin Ḥusayn band –preceded by the Lanqāwī band later inherited by Ḥamad Bin Ḥusayn after Lanqāwī’s death. This well-organized band performed fann in gathering venues, on demand, during holidays… They recorded in the early 1950’s a collection on reels that constitutes the oldest existing recordings.

Since the 1960’s, these fann are being recorded lot, either from the radio or from private jalsa.

The last type consists in the songs for special occasions’ performed by the sailors. Each of these is related to a specific occasion and they include:

- The ‘arḍa baḥriyya. In the region, the ‘arḍa implies a war song: in the past, if someone were invading the region, they would sing a specific song to a specific beat as if they were sirens to announce it. So, when sailors got close to a port, for example Bahrain, they sang a special song called the “ ‘arḍa baḥriyya” (sea ‘arḍa) to announce to the port’s population that they were coming from Kuwait –since the “ ‘arḍa baḥriyya” is specific to Kuwait–. They announced their arrival and the local population would know they were Kuwaitis.

- The sanghinī. It celebrates the restoration of the boat. After fixing the ship, sealing the cracks, painting it…etc., when the ship is ready to sail, the band sings the sanghinī, a great fann that includes large and complex sections, rhythms and dance. It is accompanied by the ṣirnāy, a wind instrument (mizmār) unlike all the other baḥrī songs.

What does this mizmār look like?

This very simple version of a clarinet is originally an African instrument called zūrnā, ṣirnāy, or sirnāy –there are many appellations.

It is used in Kuwait in the performance of two fann:

- The lēwā particular to Kuwait or to Gulf people with African roots;

- The sanghinī, a typical Kuwaiti fann.

The lēwā is the hēwā?

It is called hēwā in Basra.

The hēwā in Basra, the lēwā in Kuwait.

It is one tradition with different appellations. This beautiful and lively fann consists in dancing and ṭabl drumming, but bears no relation to the sea.

Are its percussions specific to it?

Of course, as well as its very different terminologies and community.

First: the performance of the sanghinī is accompanied by a ṣirnāy similar to, yet smaller than the one accompanying a lēwā performance.

Second: in the sanghinī, the nahhām must perform takbīr –not in the sense of “Allāh akbar”–: he must recite a specific well-known sentence to start the faṣl, such as: “Būtshī dār el-shiqa wēnah” or “Gūguī dār el-shiqa wēnah”. “Būtshī” or “Gūguī” is an Indian port hard to enter because of the rocks and the weather. It frightened them, so they asked: “Būtshī dār el-shiqa wēnah” (where is this difficult port?).

Some nahhām recited: “Nuwāḥ el-‘īd fī muna” instead “Nuwākh el-‘īs fī Mina”, Mina being a region in Holy Mecca, implying that they were going for the Ḥajj or to visit the sacred landmarks. They say “Nuwāḥ el-‘īd fī muna” instead of “Nuwākh el-‘īs fī Mina” because they are simple people. It is followed directly by the naḥba accompanied by daff i.e. the ṭār playing to a specific rhythm, and by the ṭabl played in a specific and complex way to a specific and complex rhythm.

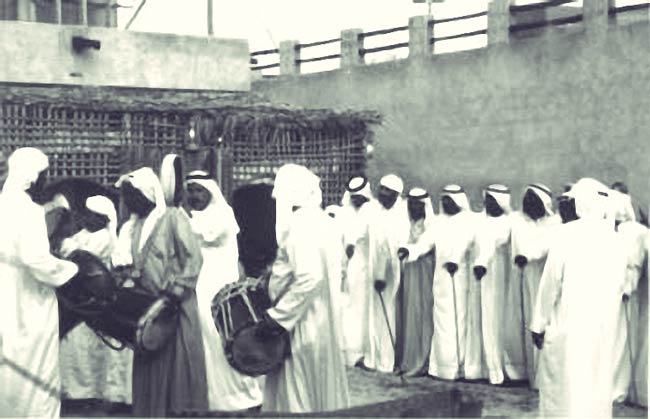

This fann is among those that must be watched, not only listened to: two rows of men stand face to face, each row singing to the other. This special song they sing with the nahhām is followed by the shubaythī, a collective song to which they sing one of two known tunes: they sing one or the other, either “Haddūm yā qalbī haddūm” or “Lī khalīl el-ḥasīn”, and a second ṭabl joins in –there was only one in the beginning– that they call khammārī. Yukhammir means: “gives the initial rhythm”. After singing and dancing to this faṣl or second part, they sometimes go –not always– to the third part called shābūrī, a dancing fann: everybody including the nahhām, the ṭabl player, and the audience stand in a circle and dance, reciting a “shēla”, i.e. “Mā lik ghēr el-fandūs” (“fandūs” is a fistful of dates) implying that “these dates are all you have got”, as if this were their ultimate goal. They sing this sentence and turn while clapping. This very lively fann ends this way.

A great thing.

A great fann indeed.

Could we play short samples of the ‘arḍa, the sanghinī, and the lēwā? … Just short excerpts to give an idea about the percussions?

Of course. It is very important to mention that sanghinī is derived from sanghīn that means “heavy” in Persian, implying that this fann is called the “heavy fann”. Its rhythmic cycle requires more than one minute maybe because of its long 64/4 rhythm. This beautiful fann includes a beautiful motion.

It consists in three very long parts, so we will only listen to one, the beginning, added to a short excerpt of the ‘arḍa baḥriyya and another short excerpt of the lēwā that, of course, bears no relation to baḥrī singing. It is performed in other circumstances, in a different society, and for different specific purposes.

(♩)

Dear listeners, we have reached the end of today’s episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

We will meet again in a new episode.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)