The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

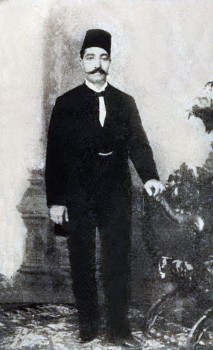

Today, we will resume our discussion about ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī with Prof. Frédéric Lagrange.

We have reached a very emotional period in ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s life and his relationship with Almaẓ.

Big celebrations required the presence of Almaẓ and ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī together.

It is said –yet I do not believe this facetious story– that this legendary duo sang about their mutual love through the songs they performed in their concerts, particularly when they were both invited to the same event. She sang in the women’s shakma or the “haremlik” on the first floor while he sang in the “selamlik” on the ground floor.

Concerning their first encounter that took place at a wedding in Gizah, it is said that she had taken a boat to cross the river and that she directly improvised a mawwāl. I doubt a ‘ālima could actually improvise a mawwāl. Anyway, she seemingly said: “Come my love. If you don’t, then I will come to you. If the sea is too deep, I will build a scaffold on my heart for you”.

Wow!

It seems that their intentions towards each other became clear when Almaẓ sang at a wedding in the Jamāliya district: “Answer, you who wish our reunion. You think it is easy, but it is difficult to reach for an ignorant. If you wish us to be together, you should gain some knowledge, because it is hard to gain my love, as you well know”. ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī answered her: “ My soul and yours were lovers in a previous life. Lovers are soul mates. Salma and Sālim” –even if it does not rime.

This tune was never recorded, not even by the early 20th century ‘ālima. Yet, we do have a recording of it –not the original tune of course– sung by Warda al-Jazā’iriyya and composed by Farīd al-Aṭrash. What do you think of this tune?

By the way, this is the only tune –or at least its madhhab– in the film that follows the 19th century’s model.

I.e. inspired by the spirit of the 19th century’s music.

All the other songs in the film are relatively modernistic.

…Modernistic and especially catastrophic…

Let us break the rule and make an exception –the first and last one–, and listen to Warda’s voice and Farīd al-Aṭrash’s melody.

With the song “Rūḥī we-rūḥak ḥabāyib min abli dah el-‘ālam w-Allāh” whose lyrics were authored by Ma’mūn al-Shinnāwī, I think.

(♩)

Now, concerning your words about the question and the answer between Almaẓ and ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī, have you noticed that what Almāẓ sings, defined as a mawwāl, is actually not a mawwāl? These are quatrains resembling Ibn ‘Arūs’ quatrains.

They may have called it a mawwāl for terminology as well as simplification purposes. The term mawwāl here neither refers to a mawwāl a‘raj nor to a mawwāl nu‘mānī, it may have been used with reference to its improvised melody, that is all.

The popular mawwāl sang by Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī or by Muḥammad al-‘Arabī are either nu‘mānī or a‘raj. While Ḥājja Zaynab al-Manṣūriyya also sings quatrains.

This may indicate the difference between the female repertoire –the repertoire of muṭriba– and the repertoire of muṭrib, so different in fact that the ladies did not sing the same mawwāl (the literary or learned music sang by women during this period). At the beginning of the 20th century –or maybe starting in the 19th century–, ladies started to sing the same repertoire as men. I think it depended on the standard of the muṭriba or the ‘ālima.

Numerous ordinary mawwāl were sang by Bamba al-‘awwāda (‘ūdist) and Asma al-Kumthariyya.

Exactly, the same mawwāl sang by Sayyid al-Ṣaftī, ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī, or Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī.

Qasṭandī Rizq’s book mentions a story told by ‘ūdist Muḥammad al-Sharbīnī: ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī and Almaẓ were invited together to a celebration organized by the students of the Military Academy. When Al-Ḥāmūlī finished his performance, he found ‘Umrān, Almaẓ’ muṭayyibātī (informal member of the band who drives the mood of the audience) getting ready to introduce her to the audience. She answered him saying: “What could I sing after Sī ‘Abduh?”. Sī ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī decided to follow the same rime and answered: “You could sing “Rayān yā fijl mā yḍurrish barḍuh” (i.e. you would sound great even if you sang about succulent radishes). Quite surprisingly, she took his words seriously and actually improvised a mawwāl with the words “Rayān yā fijl” (succulent radishes).

He meant to flatter her, not to follow her rime: his words implied that she would sound great whatever she sang.

Of course he meant that she would sound great even if she sang “Rayān yā fijl”. The point is that she took his words seriously. He did not want to pain her, he was only joking.

It is said that Almaẓ’ voice was so strong that it overshadowed the voice of all other muṭrib, and that ‘ūdist Aḥmad al-Laythī had to scream towards the “haremlik”: “Who can deny your voice, yā sitt” when he was accompanying ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s performance on the ground floor. I do not believe this story: first it is not logical, second and more importantly: having seen old houses and the distance between the “selamlik” and the “haremlik”, I can’t believe two concerts could have taken place at the same time in the same house, one in the ladies’ “haremlik” and the other in the gents’ “selamlik”.

Simply because the “haremlik” overlooked the “selamlik”, and they would have heard each other.

Moreover, the ladies liked to listen to the muṭrib’s performance, and the men liked to listen to the muṭriba’s performance, so why would they sing at the same time? This does not imply the impossibility of this occurrence… He could have been on the ground floor waiting for her to finish so that Sī ‘Abduh could start, and told her: “Who can deny your voice yā sitt” as she probably wanted to show off in order to prove to Sī ‘Abduh that she was up to his level.

He may have simply wanted to please her.

It is said that ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī sang at his own wedding accompanied by a takht including ‘ūdists Aḥmad al-Laythī and Maḥmūd al-Jumrukshī, violinist Ibrāhīm Sahlūn, qānūnist Aḥmad al-Khaṭṭāb. Of course having two ‘ūdists in the takht,knowing that‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī was a ‘ūdist himself…

Then there were three…

…An improbable takht.

The point is: he married Almāẓ, and apparently forbade her from singing at private and public events. She had to stay home, with guardians, like those bourgeois ladies.

According to Ibrāhīm al-Muwayliḥī, Khedive Ismā‘īl wished to hear Almaẓ singing after she married ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī, but the latter refused, provoking the anger of the Khedive who sent the police to Al-Ḥāmūlī’s house and tried to force Almaẓ to go and sing in the royal palace. The Khedive only pardoned Al-Ḥāmūlī through the intercession of ‘Alī al-Laythī, the court’s poet as well as Ismā‘īl’s buffoon, who praised ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s devotion as well as his respect of customs and practices. In his book, Rizq –who always defended the family of Khedive Ismā‘īl, i.e. the royal family– contradicts and criticizes this information and imputes it to the rancour between Al-Muwayliḥī’s family and the royal family, considering the trouble and problems Al-Muwayliḥī went through and his unsuccessful stock exchange ventures. I do not know if this story is true or not: ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī may have very well forbidden Almaẓ from singing at public and private events, whereas concerning the Khedive … well… What do you think?

Let us be more moderate: if the Khedive wanted Almaẓ to come, he would have brought her, and if he wanted to anger ‘Abduh, he would have done it too. He was the governor!

But did ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī really forbid Almaẓ from singing at the Khedive’s court or keep the Khedive from listening to her? He may have forbidden her to perform at public events, but did he actually forbid her to perform at the Khedive’s events too? Is it possible that the police were not able to take Almaẓ out of ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s house? ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī may have forbidden Almaẓ to sing, but does this imply that he also forbade her to sing for the Khedive? I do not know…

God knows…

Anyway, let us conclude the subject of ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s private family life: Almaẓ died leaving no children, in 1878 or 1891 depending on the –conflicting– sources.

A 13 years’ difference is quite a difference.

13 years! Moreover, something that happened in the late 19th century should be documented with more precision, at least not with such a great gap. To me though, 1878 seems closer to the truth and makes Khedive Ismā‘īl’s presence at the funerals more plausible.

It could have also been Khedive Tawfīq.

True. The point is that ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī composed dawr consistent with these terrible events that affected his personal life, i.e. dawr “Shribt el-ṣabr min ba‘d el-taṣāfī” that he sang and allegedly composed when Almaẓ passed away. Fortunately, this dawr was recorded in the voice of ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī.

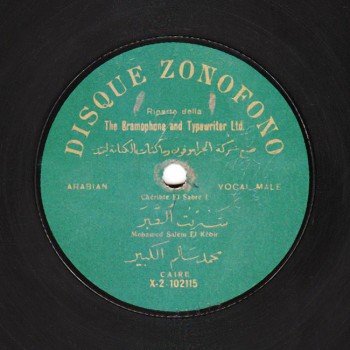

And also in the voice of Muḥammad Sālim.

Exactly. One may prefer Muḥammad Sālim’s voice, as it is the closest to Al-Ḥāmūlī’s voice.

True. Let us listen to Muḥammad Sālim singing “Shribt el-ṣabr”.

(♩)

The second crisis in ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s life is the death of his son for whom he composed the incredible dawr “Lā yā ‘ēn, lā yā ‘ēn, lā yā ‘ēn” where he says: “Lamā shuft el-badan el-badan el-badan el-badan” (When I saw the corpse, the corpse, the corpse, the corpse).

He is said to have also authored the lyrics –that actually do not require great writing skills. In fact, it is said that he actually improvised them when his son died on his wedding day.

We do not know the extent to which this story is true. You said that the lyrics do not require great effort. I think the same goes for the melody.

Of course.

It is said that his son died from a heart attack on the evening of his wedding, and that ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī appeared to the wedding guests and sang this dawr. Some say that he changed “Shribt el-rāḥ fī rawḍ el-unsi ṣāfī” to “Shribt el-ṣabr min ba‘d el-taṣāfī”… but these are just stories.

The dawr can be related to two specific events: once to the death of Almaẓ, and once to his son’s death.

Marvellous dawr “Lā yā ‘ēn” composed to the bayyātī is the first piece ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī recorded in 1908 with Gramophone on a 30cm record, # 1P and 2P.

(♩)

With these two catastrophes in the tragic life of ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī, we reach the end of the second episode about him.

We will meet again in a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh” to resume our discussion about ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī.

“Min al-Tārīkh” is brought to you by Mustafa Said.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)