The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

This is the third episode of ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s biography.

Let us stop talking about the tragedy in his life and discuss his artistic journey, with Prof. Frédéric Lagrange.

All sources agree that ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī accompanied Khedive Ismā‘īl repeatedly in his travels to Istanbul, and that he had the opportunity to sing for Sultan ‘Abdulḥamīd II.

Later on, Egypt’s Sultan Ḥusayn Kāmil who was in charge of organizing the first delegation of Egyptian musicians to the Yildiz Palace, chose a number of instrumentalists, muṭrib, and munshid headed by muṭrib ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī, munshid and muṭrib Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī, composer Muḥammad ‘Uthmān, and munshid Muḥammad al-Shanṭūrī. There were apparently strong ties between the music milieu in Egypt –notably the munshid– and the ṣūfī milieu in Turkey that had branches in almost all the countries and regions of the Middle East.

‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī visited Istanbul-Turkey repeatedly, and according to most music sources, learned a number of Turkish Ottoman musical pieces during his stays there, and chose amongst the maqām used in the Turkish literary/classical music those that could be adapted to the Egyptian taste. We have already discussed this and, as I said, these words may apply to the instrumental pieces such as bashraf and the samā‘ī. Whereas, concerning dawr and singing, I doubt the veracity of this information, despite that some of the maqām used during the era of Dāwūd Ḥusnī and Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī were not used by ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī and Muḥammad ‘Uthmān in the late 19th century. Maybe they wished to prove their mastery of the new melodies, maqām, and tunes.

You are referring to maqām such as the ḥijāz kār kurd…etc.

Exactly, as well as the bastanikār: there were no dawr to thebastanikār in the era of Al-Ḥāmūlī and ‘Uthmān. The bastanikār in the Egyptian dawr is very limited, sometimes to just one phrase in the madhhab, then the melody goes back to the ordinary pattern.

Also, most maqām used in dawr later on, either by Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī, Dāwūd Ḥusnī, or Sayyid Darwīsh, existed in the Turkish sāzindā in the 19th century, and the pattern of most of these did not exist in muwashshaḥ before.

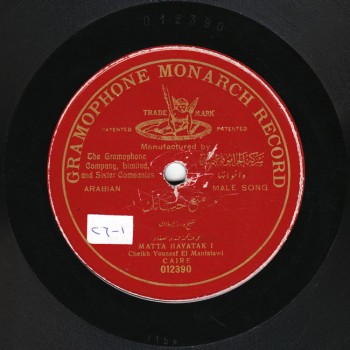

It seems that ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī had a sought-after position during Tawfīq Bāshā’s era and that he sang for him dawr “Matta‘ ḥayātak bi-el-aḥbāb” at the launching ceremony of the Ḥalwān railway.

The train railway of summer excursions.

The railway connecting Cairo and Ḥalwān where ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī spent his last days. Qasṭandī Rizq’s book “Al-mūsīqa al-sharqiyya” mentions some information that appear to be facetious, but that are in fact very significant, on how ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s singing career made him rich. It is important because it proves that a mutation happened relatively to the quality of the music in the last third of the 19th century, but more importantly that affected the position of a professional musician within the Egyptian society starting this period, when literary/classical music was associated, if I may say, with the royal court and became an art recognized by the authority, to such an extent that the latter tried to compete with the Ottoman court music during this same period.

I think that this competition against the Ottoman court music led to the great musical renaissance. The authority was generous to the musicians and gave them the opportunity to create and thus to compete with the Ottoman court music.

Al-Ḥāmūlī was a big-spender, yet his extravagance did not keep him from becoming rich and owning a 100 acre’ farm in Al-Sharqiyya, a house in Cairo –in ‘Ābdīn in the Timsāḥ (crocodile) district, close to the royal palace–, a house in Al-‘Abbāsiyya –on the same street that took his name after he passed away–, as well as a house in Ḥalwān maybe given to him by his friend Bāsīl Bēh ‘Aryān. Hasn’t this house been a ruin for some years now?

The garden around it was sold, but the house still exists and is surrounded by a squatter area. Ḥalwān’s situation also degraded: from a great summer resort and touristic area, it is now full of cement plants, iron plants, steel mills, and pollution. The whole region degraded: from a cure centre, it has become one of Egypt’s most polluted regions.

A tearful thought for the beautiful past.

The beautiful past refers to the 19th century, not to the 1950’s of course.

Let us listen to Sheikh Yūsuf singing “Matti‘ ḥayātak” as we haven’t yet listened to anything by him.

(♩)

Qasṭandī Rizq’s book pinpoints an important matter: private concerts were not‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s only source of income, neither was the authority’s monthly allowance (Khedives Ismā‘īl, Tawfīq, then ‘Abbās). There were also public concerts –first in large tents then at the theatre– for which people bought tickets. Music was not only used for celebrations such as weddings, circumcisions, “subū‘ ” (Egyptian celebration held 7 days after a child’s birth), there were also repeated concerts that allowed city folk to attend music concerts in large tents or theatres whenever they wished.

This practice and revolution in the music industry started in the last decades, maybe the last third of the 19th century.

Lebanese poet Khalīl Muṭrān –who lived in Egypt– assisted in Alexandria to a concert held in a huge tent where Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī performed 3 waṣla attended by an audience of one thousand who had paid an entrance fee.

One thousand is of course a very large number. These muṭrib sang with no microphone or any other kind of voice amplifier, thus it was very difficult –especially in a tent– for a singer’s voice, as powerful as it may have been, to reach 1000 persons.

If we consider the theatres built in the 19th century such as the Opera or the Azbakiyya theatre, among others…

Don’t you think the word “tent” may imply a theatre? …Were public concerts actually organized on the street?

On the streets, yet in big cities of course…

I do not think the word “tent” was used instead of “theatre” or “theatro” (as they called it in the 19th century): tents are tents and are built temporarily then removed after the concerts.

The capacity of a theatre can reach one thousand persons, but I doubt that a tent’s could also reach this number.

The voice can reach 200 persons at most, which is already extraordinary and demonstrates the power of a muṭrib’s voice.

The following is important: to me, ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī –not ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī the person– symbolizes the mutation of the muṭrib’s placeas well as of music’s position within the Egyptian society at the end of the 19th century.

In his book “Al-mūsīqī al-sharqī”, Kāmil al-Khula‘ī wrote: “The deceased was a generous soul, ambitious, and aimed at climbing up the social ladder –from the muṭrib class to high-society– by practicing his art for the sake of art”, i.e. to ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī as well as Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī, earning wages at the end of a concert was degrading. Thus, muṭrib never took the money by hand: the muṭayyibātī (informal member of the band who drives the mood of the audience) took it then gave to the muṭrib who acted like a guest and not like a salaried employee. Al-Khula‘ī adds: “Because of people’s ignorance in the past of the superiority of this art and the magnificence of its position among arts… Knowing that Plato, the wisest of the wise, described it as the door to wisdom and the first degree of civility. The 19th century is the century of the musician’s mutation from a salaried bohemian who was invited with condescendence into bourgeois homes, to a bourgeois himself at the end of this century.

His family life shows that his craft –“craft” because this word in the Arabic language is different form the word “profession”. Today, one talks about the muṭrib’s “profession”, not his “craft” because the word “craft” conveys the idea of handicraft. He was indeed an artisan in the music industry to a certain extent…

…So this craft –that may have become a profession– did not present a hindrance to big marriages: added to Prof. Sha‘bān’s daughter and Almaẓ, Al-Ḥāmūlī married three times. His third wife gave him his son Maḥmūd who died young on his wedding day (we have talked about dawr “Lā yā ‘ēn”). Another wife gave him his son Muḥammad who was still a child when Al-Ḥāmūlī died in 1901 in Ḥalwān. His last wife was Turkish, and one only needs to mention her name Gulnār Hānim to know that she was of Ottoman origin.

A title.

A title exactly.

I think Khalīl Muṭrān’s words on ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s style, especially when compared to Muḥammad ‘Uthmān’s, are the most eloquent.

Before reading Khalīl Muṭrān’s words, we must highlight that ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s style was simple and never spectacular.

The spectacular aspect in ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s performance lies in his singing more than in his melody.

Exactly the point of Khalīl Muṭrān who wrote: “ ‘Abduh was an innovator who created melodies out of the moment’s inspiration, confusing the skilled and delighting the listeners with his power to entertain them with his notes. He may have broken rules, left familiar grounds, then flew, and soared”.

Let us stop here and analyse the meaning of these words: Muṭrān may have implied that when ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī composed a dawr to a specific maqām, he could go to a maqām that was not associated with the dawr’s original maqām, unleash his immediate imagination, and compose on the spot.

Such as “Lisān al-dam‘ ” that he started to the ‘irāq and ended to the bayyātī.

Exactly. We could listen to this rare recording in the voice of ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī on the second side or…

…The second cylinder record.

The second cylinder record of dawr “Lisān al-dam‘ ”.

(♩)

Go on sir.

Khalīl Muṭrān says: “He muted the ‘ūd, exhausted the qānūn, and silenced the nāy”. Does this mean that the instruments accompanying the takht stopped playing so that he could sing a cappella? Or that they experienced a kind of stage fright when Sī ‘Abduh’s performed? I do not know. Maybe they simply let him sing a cappella for a few seconds.

Or gave him the rhythm.

“He unleashed his voice, delighting in the sky of ṭarab… from the eagle’s leap to the flood, to the quick lightning, to the night warbling, to the pigeons’ cooing, to the brook’s moaning… This voice was high, low, strong, weak, sonorous, trembling, satiating, tenuous… The notes uniting as origins and separating as sub-branches, doubling up or going solo, coming closer or separating, interconnecting or disconnecting, relaying one to the other, in sequence according to the soundness of taste and the artistic talent, ending at the qarār.”

Then Khalīl Muṭrān compares ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī to his greatest competitor Muḥammad ‘Uthmān saying: “ ‘Uthmān was a great composer as to the structure of melodies”. The word “composer” is very important. Khalīl Muṭrān describes ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī as an “an innovator who creates the melody”, while he describes ‘Uthmān as “a skilled composer”: genius on one side and skill on the other. He seems to have stripped Muḥammad ‘Uthmān of artistic genius, creativeness and innovation, and described him as a skilled craftsman. To Khalīl Muṭrān, Muḥammad ‘Uthmān was a craftsman, a “skilled composer as to the structure of the melodies, skilled in removing the notes from their position and uniting them in a pleasant harmony”. Once again, the word “harmony” refers to the concept of organizing, of classifying skilfully different ideas. “He was passionate about his craft, serious in perfecting it, in order to make up for the lack of a pleasant voice with a good style and a smooth course. This is why he never sang solo and was always accompanied by instruments”.

“He was passionate about his craft, serious in perfecting it, in order to make up for the lack of a pleasant voice with a good style and a smooth course”. To Khalīl Muṭrān, Muḥammad ‘Uthmān was not a muṭrib, at least not a brilliant muṭrib. He saw him as an ordinary performer, yet a first rank composer. He adds: “This is why he never sang solo and was always accompanied by instruments”. When he composed a song and performed it for the first time, it sounded well-made, well-structured, and beautiful to listen to, but bearing the traces of hard work and the scent of the wax burnt during the nights to produce its parts”.

These are very harsh words, aren’t they?

Harsh but also beautiful… These are two opposite schools.

True. In this text, Muḥammad ‘Uthmān represents the set melody, while ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī represents the tendency towards ornamenting onto a very limited melodic canvas that can be endlessly developed by the creative muṭrib.

Whereas there is no blank canvas with Muḥammad ‘Uthmān since he was the composer. The wax burnt during the nights to produce the parts of the piece, the idea that the first performance of the melody right after Muḥammad ‘Uthmān had composed it showed that it was not completely ready… His lines convey that even though the melody was complete, well-structured, and beautiful to listen to, it still lacked something.

I think he meant that it lacked the improvisation and taṭrīb that ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī performed.

Let us not forget:

That there are different types of improvisation including the ornamental improvisation that I think any able muṭrib can perform. Whereas the type Khalīl Muṭrān means here is the type performed by ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī that was of a much higher standard than ornamental improvisation, reaching the level of creative melody improvisation, removing or adding most of the time melodic phrases the initial composer may have not thought of;

And that the dawr only finds its place and becomes part of this musical repertoire shared by this generation of muṭrib when such a muṭrib tames the genius melody he received. This is a very courageous concept relatively to the Arab custom since heritage books explain that what is received from ancestors must be relayed as is.

These works, whether in prose or in verse, can’t undergo any changes, because changing is considered as corrupting. The idea presented here opposes traditional thinking because it considers changing as enriching, not corrupting.

After writing “the scent of the wax burnt during the nights to produce its parts and direct its paths and the harmony between its notes and its meanings”, Khalīl Muṭrān addsthat this does not imply that ‘Uthmān was not ‘Abduh’s counterpart, and that he demonstrated through the outcome of his work that good authorship has a place along with innovation, and that hard work could be as important as creation. Hard work on one side, creation on the other. The Arab music genius is probably based on this controversial relation between hard work and creation. Moreover, the hard worker may have an advantage over the creator as he is the one who prepares for him the creating material. With this phrase, Khalīl Muṭrān actually places the hard worker in the service of the creator, still I feel that there is a kind of hierarchy among them, i.e. someone gives the creator the material that he needs, but the creator is the only one who can develop this raw material and extract a real gem from it.

Khalīl Muṭrān added: “It is true that ‘Uthmān, in the end of those last years, had composed most melodies. ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī took them and embellished them at will, metamorphosing pretty peasant-girls into crowned queens”.

These are very harsh words: they imply that the melodies composed by Muḥammad ‘Uthmān were merely pretty country-girls with a peasant bearing that required some polishing in order to be welcomed into civilized milieux. “Metamorphosing someone who is beautiful to look at into a spirit scented by a lover’s heart”. Thus ‘Uthmān renewed ‘Abduh’s spirit for the listeners, while ‘Abduh brought to them ‘Uthmān’s science. They complemented each other despite their mutual jealousy, reciprocal detestation, and divergence.

Do you really believe that there was jealousy, detestation, and divergence between them?

If there had been jealousy, detestation, and divergence between them, would he have sung his melodies? Is it logical? Records did not yet exist, so he surely had to listen to him live… If these reciprocal sentiments existed, he would have neither listened to him nor memorized his melodies.

Certainly not…

But I think that the relationship between the creative and the hard-worker was reversed later on in the 1930’s and 1940’s. The composer became the creative and the muṭrib became the hard-worker who added simple details. Creating became the composer’s responsibility.

Exactly. To a point where the composer displayed his genius and the muṭrib followed him instead of leading him.

Exactly. So I think that this controversy was reversed later on with the concept of authoring a melody for a performance whether for a recording company or for a concert.

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

We will meet again in our next episode to resume our discussion about Al-Ḥāmūlī.

“Min al-Tārīkh” is brought to you by Mustafa Said.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)