The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Dear listeners, welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Today’s episode is about a major figure of Arab music in the late 19th century and early 20th century. I am referring to Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī who was born in Damanhūr and spent his life in Cairo where he died around 1927.

Do you plan on stealing from me what little information I have got?

Every episode you participate in, you are the only one talking while I sit aside. It is unfair…

Ok… Go ahead then… Talk!

Today, Mr. Frédéric Lagrange will be telling us about Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī, the star of this episode.

The little information we have on the unrivalled composer Ibrāhīm Muḥammad Ḥasan al-Wakīl, known as Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī, comes from his biography written by his son and printed in 1977, and from Tawfīq Zakī’s book published in 1990. The rest can be deduced from his recordings, those in his voice as well as those interpreted by the many muṭrib who sang to his melodies.

He was probably born around 1852 in Damanhūr, yet this information is not confirmed.

The point is…

According to the above-mentioned sources, Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī was born in Damanhūr to a devout family and his father was very stern, almost austere in fact. After he was born, his family moved to Cairo where he studied in popular neighbourhoods under the ṣahbajī while attending the concerts of the great masters of the Khedivial school, i.e. Muḥammad ‘Uthmān and ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī.

Strangely, he neither started his musical learning under muṭrib nor under ‘ūd or qānūn players, but under the riqq players of the period’s various takht who taught him about the musical meters. He only learned ‘ūd playing later on.

Some sources affirm that he worked as an employee… Yet how could a young man be an employee and learn riqq playing and ‘ūd playing all at once? What do you think?

Note that the concept of an employee in the last third of the 19th century is quite different from what it is in the early 21st century. Back then, employees were afandī: the disc catalogues list him as Ibrāhīm Afandī al-Qabbānī, where Afandī refers to everything this title implied in 1870 or 1880.

Can we perceive a 20 or 30 year’ old young man as an Afandī learning to play an instrument and singing in a takht? This sounds a little contradictory to me.

Well if Bēh were learning music under the period’s great instrumentalists and musicians, why wouldn’t Afandī do the same?

The information I am unsure of is that he did not study under ‘Uthmān and ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī and started his musical learning with the meters…etc. If this were true and he only learned ‘ūd late in life, then why didn’t he compose muwashshaḥ?

It is said that he started with the meters and learned ‘ūd later, not late in life.

Still, I agree with you concerning the muwashshaḥ… If he had started with musical meters, then why didn’t he compose muwashshaḥ, or include more rhythmic shifts in his dawr? There are some in his last dawr such as in “El-fu’ād makhlū’ li-ḥubbak” for example. But all his other dawr are composed to one rhythmic beat, aren’t they?

They are, except for his dawr composed to the aqsāq and “El-fu’ād makhlū’ li-ḥubbak”. Still, I feel that he must have studied somehow under Muḥammad ‘Uthmān.

When he moved to Cairo… Yet, according to the above-mentioned sources, following his father’s opposition, he settled alone in Banhā where he studied under Sheikh Salīm Rizq whose daughter he married, then roamed throughout the cities of the Delta such as Zaqāzīq where he apparently sang in 1875 in Mr. Georgi’s café. So his career seems to have started off in popular cafés.

Which brings us back to our employee issue… Did employees sing in cafés in 1875?

…For more income!

Right… It can’t hurt!

Then he tried his luck in composing mostly dawr in the beginning, which may indicate that he must have studied under Muḥammad ‘Uthmān or ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī.

After his father died, he went back to Cairo and became a sought-after composer as well as a muṭrib. He had a beautiful voice and his performance was excellent. Comparing his recordings to Dāwūd Ḥusnī’s shows that his voice was both more melodious and touching.

I like Dāwūd Ḥusnī’s voice a lot though, but I do not deny that Al-Qabbānī sang well.

Why are you so intent on contradicting me today?

You do not know why?

As a muṭrib, his voice was of course rich with possibilities and ornamentations, even more than Dāwūd Ḥusnī’s. Moreover, he was clearly more of a professional singer than Dāwūd Ḥusnī. In his memoirs, Sāmī al-Shawwā mentioned that he first played in the takht of Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī who sang in a café in the Azbakiyya.

The appellation “Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī’s takht” confirms that he was considered first a muṭrib and second a composer at his beginnings, and only later on first a composer and second a muṭrib.

Some say that he stopped singing because his voice was affected by some illness… I do not believe this story.

His first recordings were made during the 1903 recording campaign, which implies that he was a second rank muṭrib. One must accept the truth. The 1903 recording campaign in the Middle East did not include the great muṭrib.

The two and only famous muṭrib who recorded during the first recording campaign in 1903 are Sayyid al-Ṣaftī and Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī. The rest includes unknown muṭrib such as Maḥmūd al-Teleghrāfjī.

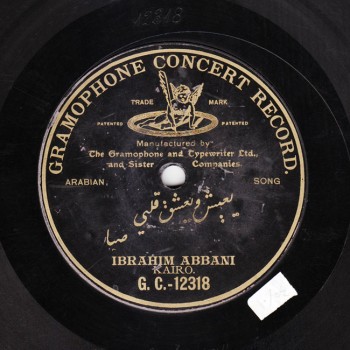

Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī recorded 4 pieces:“ Bi-kulli marsūm”, the mawwāl Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī also sang; a qaṣīda we know nothing about, because its label strangely only carries the title qaṣīda with nothing added.

Muḥammad Salīm also recorded a qaṣīda with Odeon late in 1904. Listening to the disc reveals that it is qaṣīda “Arāka ‘aṣiyy al-dam‘ ”. So he recorded “Arāka ‘aṣiyy al-dam‘ ” and God knows what else.

He may have recorded “Arāka ‘aṣiyy al-dam‘ ”… Let us hope we will find the disc and discover what is recorded on it.

In 1903, he recorded beautiful dawr “Yi‘īsh we-ye‘sha’ albī” composed to the ṣabā and that was also recorded by Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī on a Sama‘ al-Mulūk record; and “El-dalāl mawadda”.

You mean “El-dalāl mūḍa”… Yes, yes… Just listen…

(♩)

Ok. Let us listen to this generation’s interpretation of dawr “Yi‘īsh we-ye‘sha’ albī” because he sings it beautifully. The dawr was recorded in 1903 and concludes the disc…

(♩)

So, Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī entered ‘Abd al-Raḥīm al-Maslūb’s family by marrying his daughter.

Also, in the early 20th century, after ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī and Muḥammad ‘Uthmān passed away, and after Al-Maslūb stopped his musical production, the Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī / Dāwūd Ḥusnī duo became the major composers in the field of learned/literary music.

What is the story with musicians marrying the daughters of other musicians? The same thing happened with ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī…

This is an important point. The information in the old sources concerning these marriages in the music milieu may indicate the symbolic musical succession/inheritance through marriage, don’t you think?

Maybe… The same as with kings in our History…

Al-Qabbānī was a pillar of the Oriental Music Institute and became President of the Musicians’ Union when it was established in 1920. At this point, his artistic imagination had started running out: his last melodies were composed right after WW1, and they are chronologically: “El-fu’ād makhlū’ li-ḥubbak” recorded in 1915 by Zakī Murād. Let us assume that he had thought about this melody starting 1914; followed by the 1919 recordings also in Zakī Murād’a voice; he also composed the beautiful melody of dawr “Yā qamar dārī al-‘uyūn” to the nawā athar.

We could listen to both these melodies. Yet, unlike them, to my knowledge Al-Qabbānī did not compose anything after 1919-20. If he did, I do not know who recorded them.

(♩)

I do not think… There are no record company catalogues that say… I do not know about the system during live performances…

At the time, the position of record companies had changed drastically and all compositions were now recorded, none went unrecorded. Consequently, I do not believe Al-Qabbānī composed a melody that went unrecorded.

It is possible… considering that after 1920, Gramophone’s star dimmed down, except concerning Umm Kulthūm. The difference between the number of Gramophone’s recordings made before WW1 and after the war until 1920, and those made after 1920 shows that its production had almost stopped except for Umm Kulthūm and ‘Abd al-Wahāb who allowed the company to stay in the market, while Baidaphon, Polyphon, and the other record companies were leading it.

I honestly have another belief: I think that Gramophone, in the late 1910’s and the early 1920’s, recorded no less than 6 times as much as the other record companies, i.e. if Baidaphon’s catalogue listed 100 discs, Gramophone’s listed 600 in the 1920’s for example, while they made the same number of recordings in the 1930’s, none recorded more than the other.

Exactly. This can create the impression that Gramophone lost its leading position in the market, a position it had enjoyed between 1906 and 1917-18.

So, Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī stopped composing after 1919-20, yet remained a pillar of the Oriental Music Institute and the President of the Musicians’ Union.

As for his production –i.e. the musical forms he composed–, it was very limited regarding all the musical forms except for the dawr. The mawwāl being an improvised form is not considered to be a composition, and Al-Qabbānī composed two of those that were recorded: “Bi-kulli marsūm amarnī el-ḥubb we-nahānī” and political mawwāl dedicated to Muṣṭafa Kāmil Bāshā who died in 1908, which he sang most probably in 1908-1909. But these are improvised forms, not composed forms…

(♩)

There is also the aforementioned mysterious qaṣīda. After that, he only composed dawr, unlike Dāwūd Ḥusnī who tackled almost all the composed forms: theatre tunes as well as ṭaqṭūqa, dawr, and monologues… While on the other hand, Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī, known as Dāwūd Ḥusnī’s first competitor, only composed dawr… incredible dawr indeed!

They are truly great, yet we know nothing about his voice during live performances.

Sāmī al-Shawwā said that Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī was knowledgeable as to muwashshaḥ melodies that he also sang, and that he personally helped him memorize several bashraf and instrumental pieces. So he obviously was knowledgeable in those too. Still, his ‘ūd playing was limited as he only included one taqsīma in one work. He seems to have been knowledgeable in these matters, so why did he neither record nor compose any?

You have piqued my curiosity, what is the orphan taqsīma you are talking about?

A beautiful taqsīma to the bashraf qarābatāk sīkāh where he later shifts to the bamb. We could listen to part or all the piece.

Let us listen to the taqsīma at least.

Ok…

(♩)

He was indeed known as a very good ‘ūd player, so good in fact that he gave ‘ūd lessons to Umm Kulthūm. This is not a rumour, it is proven: in his book on his father, his son published a photograph of a slip signed by Umm Kulthūm representing either a down-payment for ‘ūd lessons, or a credit voucher to Al-Qabbānī for lessons, a kind of agreement between them. …Very funny!

They wrote everything in those times, nobody does this anymore.

He may have also taught ‘Abd al-Wahāb, at the beginning of the latter’s career and Umm Kulthūm’s.

(♩)

He was the President of the Musicians’ Union and studied at the Oriental Music Institute where ‘Abd al-Wahāb had also studied… So, why not…?

Concerning his relationships with non-Egyptian muṭrib, these sources highlight his friendship with Lebanese Beiruti muṭrib and buzuq player Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn. The latter used to visit Cairo where they met and started a solid friendship.

A friend with an age difference.

Dear listeners,

We have reached the end of our first episode on Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī.

We will meet again in a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

“Min al-Tārīkh” is brought to you by Mustafa Said.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)