The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

“H-allāh, h-allāh yā Abū Shōna”

“Ḥāḍir” (Yes, Sir).

Dear listeners, welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Today’s episode is dedicated to the author of this famous jest, Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd. Our quasi-permanent guest Prof. Frédéric Lagrange will be telling us about him.

Good morning.

Farīd Abū Shōna.

Farīd Abū Shōna… yes…

Exactly…

Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd, Sulaymān Afandī Abū Dāwūd.

The mysterious being…

The mysterious man…

There is no confirmed information on Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd.

The only document that gives a foggy idea about him is a single unclear photo printed in one of Kāmil al-Khula‘ī’s books –“Al-aghānī al-‘aṣriyya” or “Nayl al-amānī fī durūb al-aghānī”–, knowing that the book’s format may change depending on the edition, and that photos are sometimes added in the end. This photograph shows a smartly dressed 45 or 50 year’ old man, wearing an Istanbul suit and a ṭarbūsh and holding a “ ‘aṣāya bi-nuṣṣ” (cane) like mountain notables.

He is introduced as the “literate muṭrib”, which means nothing because this same source introduces all Afandī as “literate muṭrib”. Thus they are only differentiating between Sheikh and Afandī.

Between Sheikh and Afandī…

Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd may have been Jewish, as widely spread in the 60’s and 70’s music milieu among amateurs and old record collectors. Aḥmad ‘Abd al-Majīd’s book published in 1970 “Li-kulli ughniya qiṣṣa” (There is a story behind every song) is the only source that talks about Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd’s religion. Today, some Internet websites include Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd within the Egyptian Jewish musicians along with Dāwūd Ḥusnī and a number of muṭriba.

Zakī Murād.

And of course, Zakī Murād.

Old sources, books printed in the early 20th century, do not give any information about him.

Maybe because the issue of religion was not very important to them.

I think that the only element we can rely on to confirm his religious affiliation is his name: Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd may be a Jewish name… Still, it can also be a Muslim name.

Another element in relation to this issue is the only qaṣīda he recorded: “Ilzam bāb rabbik”

That almost fully consists in praising “Ahl al-Bayt” (the family of the Prophet Muḥammad).

The Muslim aspect of this qaṣīda may contravene the assumption that he was Jewish, even though Zakī Murād –who was Jewish without any doubt– recorded qaṣīda “Al-aytām” –bearing a Muslim aspect– for a Muslim charity organisation. Yet this qaṣīda is different from “Ilzam bāb rabbik” that is a religious qaṣīda.

Again, it seems that the issue of religion was not very important to them, then.

Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd, the artist, almost recorded exclusively dawr, except for 7 or 8 mawwāl at most.

All of which were only “additions”.

Except for mawwāl “Min el-maḥabba” recorded by Zonophone!

I got you there, didn’t I?

You are 100% right, Professor.

(♩)

We must admit that this single and strange qaṣīda “Ilzam bāb rabbik” –the only recorded one we have– does not display any genius in qaṣīda performance.

But it shows something else, that there was another way to chant qaṣīda besides the “ ‘awādhil”: the way followed in dhikr ceremonies, as he chanted it as if he were in a dhikr ceremony.

“Ilzam bāb rabbik” is a qaṣīda as to its musical form, not its poetic form, since the text is not that of a qaṣīda.

We must differentiate between the qaṣīda as a musical form and the qaṣīda as a poetic form. Sometimes, there is no full consistency between both definitions of a qaṣīda.

“Ilzam bāb rabbik” is not a qaṣīda as a poetic form because the language is in between colloquial Arabic and literary Arabic, yet closer to the latter.

On the other hand, it is a qaṣīda as a musical form. Yet, as mentioned earlier, its performance does not follow the “‘awādhil” way, i.e. Al-Manyalāwī or ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī’s way.

The Nahḍa way.

(♩)

He seems to have specialized in dawr performance: The list of his numerous recordings with all record companies –he is among those who recorded with all the record companies at the beginning of the century, like ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī–, portrays him as a dawr encyclopaedia as he recorded dawr authored by almost all the composers, including the early dawr in their quasi-primary structure, and those composed by his contemporaries such as Al-Qabbānī and Dāwūd Ḥusnī. He also recorded works composed by Muḥammad ‘Uthmān and Al-Ḥāmūlī, of course. On the other hand, he recorded dawr composed by Aḥmad Ghanīma, Al-Maslūb (more than one dawr), and Al-Khaḍarāwī, who were not as famous as ‘Uthmān and ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī.

We said that he specialized in dawr in relation with his recordings and not his live performances. God knows about those.

I think that the recordings of a certain artist can’t convey a true idea of his style or performance, or his strategy in choosing the musical works. Though they certainly do reflect some aspect.

Yet, I do agree with you in relation to his performance of waṣla that include all these compulsory components necessary to reach the dawr. He undoubtedly sang qaṣīda, mawwāl, layālī and muwashshaḥ, yet they seem to have been, to him, merely introductions to reach the main part of the performance, i.e. the dawr.

I think that, like Sayyid al-Ṣaftī, he may have also performed a variety of different forms that he recorded… God only knows.

Now concerning the dates: It seems that he did not record after 1914. Moreover, even though his name is mentioned in the catalogues of record companies such as Baidaphon or Odeon up until the 20’s, his name as “the late Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd” was never mentioned in any of these catalogues, up until it disappeared from those catalogues that disappeared themselves completely in the 30’s.

So, he was either forgotten completely, or we can assume that he was still alive until the 20’s maybe, but that he had stopped singing.

Or that he had stopped recording.

Or that he stopped recording… But, could he have stopped recording without having stopped singing?

Sayyid al-Ṣaftī, for example, started recording less in the early 20’s. But recordings prove that he did not stop completely. The same goes for Zakī Murād.

So Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd either left the artistic milieu altogether, or only stopped recording, as you said. Maybe the record companies did not make him any interesting offers.

So, let us assume that he kept on singing during the period between 1890 and 1915 or 1920… But these are only assumptions.

In conclusion, we have been talking from the beginning about a person whom we know nothing about besides the musical heritage he left. So, let us base our analysis on this musical heritage.

Now concerning his voice: I do not know if you will agree with me but I think that the voice that most resembles Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd’s is Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s. They share the same tonality, the same texture. Yet their performance strategies are different, as Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd’s suave voice resembles Al-Manyalāwī’s.

His voice was soft too.

True. But it also resembles Al-Manyalāwī’s, only without the latter’s craziness.

… Without the latter’s impishness…

Right… Without the impishness in Al-Manyalāwī’s performance.

They were also of a different standard.

Can’t we just say that Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd sang without the touch added by Sheikh in general, that also influenced Afandī later on. What I mean is that the impishness and the sometimes exaggerated melody show-off was added by Sheikh to the Afandī’s performance. So why can’t we just say that Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd’s performance followed the 19th century’s style?

Because there were also differences among Afandī’s performances…

True. It is not as simple as ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī’s performance.

Exactly. Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd’s performance and ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī’s performance have nothing in common. Their ways were completely different: Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd’s way is almost like Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s, excluding the sadness.

And excluding “trustworthy muṭrib” Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s “trustworthiness”: the difference between Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s recordings of dawr made by different record companies is limited to individual ornamentations. The pattern is the same, unlike ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī. Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd performs some variations.

His performance is characterised by a creativeness that is not necessarily coupled with the impishness, or the melodic and performance show-off that characterize Al-Manyalāwī’s performance for example.

Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd rejects tragedy… this is the fundamental difference between him and ‘Abd al-Ḥayy.

True… He tried to add some live elements to his recording such as “Allāh, allāh yā Abū Dāwūd” and “Ḥāḍir”. He was the only one who did this until others tried to imitate him, such as Sayyid al-Ṣaftī. But I think that he invented this style: talking during a live performance.

A joyful and jocular spirit characterizes his recordings… “Zaman el-alsh el-gamīl” (the period of pleasant jokes)…

“Zaman el-alsh el-gamīl, mush el-alsh el-rakhīṣ” (the period of pleasant jokes, not cheap jokes)

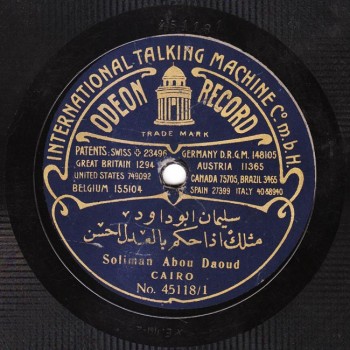

Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd’s recordings made by Odeon are known for the following joyful jest included in almost all his discs: at the start of the second record-side, a muṭayyabātī –maybe one of the takht members– says “Allāh, allāh yā Abū Dāwūd”, and the muṭrib answers “Ḥāḍir” then starts singing.

A good example of this jest is his recording of dawr “Mithlak idhā ḥakam bi-el-‘adli aḥsan”, i.e. Al-Khaḍarāwī’s dawr “Al-huzām” recorded by Odeon: the first side ends with Sulaymān Abū Dāwūd saying: “Irḥam irḥam”, and the second side starts with the muṭayyabātī telling him: “Irḥam yā abū Dāwūd” to which he answers: “Ḥāḍir” and resumes the dawr.

Let us listen to him.

(♩)

Dear listeners,

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Min al-Tārīkh” dedicated to Sulaymān Afandī Abū Dāwūd.

We thank Prof. Frédéric Lagrange and we thank you for listening.

We will meet again in a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh” to resume our discussion about Sulaymān Afandī Abū Dāwūd.

“Min al-Tārīkh” is brought to you by Mustafa Said.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)