The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Sama‘ ”.

“Sama‘ ” discusses our musical heritage through comparison and analysis…

A concept by Mustafa Said.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Sama ‘ ”.

Today, we will analyse a –mostly improvised, not fixed– instrumental work: the bayyātī taḥmīla.

We discussed the taḥmīla form in a previous episode, defining it amongst instrumental forms as the equivalent of the dawr amongst vocal forms, as it includes a fixed melody as well as improvisation on this melody, like the henk: a dialogue between the solo instrumentalist and the ensemble.

The difference between the taḥmīla and the dawr is as follows:

In dawr, the tafrīd is performed by a single muṭrib. We never came across a recording of a dawr sung by more.

On the other hand, many muḥaddith mentioned that ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī and Sayyid al-Safṭī –‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī being obviously the most famous of both– sang a dawr together in a live performance: each performing tafrīd on one of the waḥāyid …no one knows how.

Ordinarily, or traditionally, a single muṭrib sings the dawr: only the muṭrib invited to the evening/concert performs tafrīd in the dawr.

Whereas, in the taḥmīla, the band members perform tafrīd in turn: the instrumentalists in turn improvise on the initial melody and on the ascending notes when applicable.

The taḥmīla, or melody, we have, was played to the bayyātī in the following version…

(♩)

…and to the ṣabā in the following version…

(♩)

Our two recordings to the bayyātī are trios, including a duo who improvise:

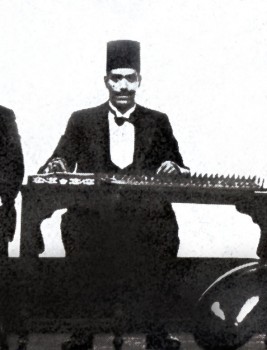

The first trio: Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād (qānūn), Ibrāhīm Sahlūn (kamān), and Muḥammad Abū Kāmil al-raqqāq (percussions).

The second –and more recent– trio: Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān (qānūn), Sāmī al-Shawwā (kamān), and Maḥmūd Raḥmī (percussions).

The percussionist did not play a role in the taḥmīla because the riqq is a percussion instrument, not a melodic instrument, and the taḥmīl requires an instrument that can play the melody. On the other hand, he did play a role in the raqṣ that resembles the taḥmīla, and had an important role in live performances.

As for the melody, our two duos are:

Ibrāhīm Sahlūn and Al-‘Aqqād in one recording;

Sāmī al-Shawwā and Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān in the other recording.

…and they play the same instruments, kamanja and qānūn:

Ibrāhīm Sahlūn and Sāmī al-Shawwā (kamān);

Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād and Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān (qānūn).

Ibrāhīm Sahlūn and Sāmī al-Shawwā play the same instrument exactly. The difference only lies in the period and the evolution that affected their performance.

Whereas, Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād and Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān do not play the same instrument:

Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād’s qānūn does not have the ‘urab that make shifting from one scale to another easier.

Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān uses these copper ‘urab placed at the left of his instrumental right before the pegs.

These ‘urab help shift from the jahārkāh up to the ḥijāz for example, or shift from the nawa down to the ṣabā.

Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād and his fellow musician ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī refused to use these ‘urab, while their generation includes Maqṣūd Kalkajian, for example, who did use them. The following generation including Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān, ‘Alī al-Rashīdī, and sometimes Muḥammad ‘Umar, always played the qānūn with ‘urab.

Let us illustrate the difference between two phrases:

In the phrase played by Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād, the down-up picking on the qānūn is clearly heard…

(♩)

…while, with Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān…

(♩)

…it sounds like a free string, because the copper ‘urab have replaced the anf (nose).

With Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād, the finger is not sharp enough to pick the string as well as the copper ‘urab. Also, when he picks with his finger, he reaches something that is infinite, as there is no neck to help make the sound clearer.

Now let us go to Sāmī and Ibrāhīm Sahlūn… Let us listen to a phrase played by Ibrāhīm Sahlūn and a corresponding phrase played by Sāmī al-Shawwā.

(♩)

Ibrāhīm Sahlūn’s arches are shorter and his edges are less.

Sāmī al-Shawwā seems technically much more experienced than Ibrāhīm Sahlūn. His maqām phrase is longer, i.e. he uses more scales on one maqām.

Each style has its own beauty, the simple as well as the more complex –free from acrobatics–.

We have talked about technical issues.

Now let us see where each one of them went:

Ibrāhīm Sahlūn plays to the bayyātī then changes the sub-maqām and plays to the shūrī. He then changes the initial maqām –the fourth– and shifts to the ṣabā, followed by the ḥijāz, thus shifting completely from the original, even changing the jins from an Arabic jins to a varied jins, i.e. he changes from the jins from which derive the rāst, the sīkāh, and the bayyātī, to the jins from which derive the ḥijāz or the awj for example. So, he performs a full shift to the ḥijāz…

(♩)

Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād, along with Ibrāhīm Sahlūn, shifts to the ṣabā and to the shūrī…

(♩)

…with everything of course following the down-up-picking technique.

Sāmī performs more shifts. He plays to the initial then shifts to the ‘ushshāq, which also includes a jins change –from the Arabic jins we talked about, to the strong jins from which derive the jahārkāh, the ‘ushshāq, and the kurdī…

(♩)

…while Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān shifts a lot to the ṣabā…

(♩)

…and displays the whole bayyātī: sometimes playing a full ascending dīwān, and sometimes playing a full descending one, of course using the ‘urab to change the scales such as changing from the awj to the ‘ajam…etc.

(♩)

The pattern of the taḥmīla includes an initial phrase, i.e. the lāzima is the taslīm itself out of which the instruments improvise phrases…

(♩)

…followed by ascending notes that are all to the same maqām, i.e. unlike the rāst taḥmīla that includes sīkāh jahārkāh nawa.

Here is the first ascending phrase…

(♩)

Here is the second ascending phrase…

(♩)

In these ascending notes, the difference lies in the rhythm not in the melody, i.e. the second ascending phrase’s rhythm is the double of the first ascending phrase’s rhythm.

Here is the first ascending phrase again…

(♩)

…and, again, the second ascending phrase…

(♩)

As you have noticed, the second ascending phrase’s rhythm is the double of the first ascending phrase’s rhythm.

Here are some general remarks before we listen to the recordings in full:

The first remark: the taḥmīla itself was played as a dūlāb in some songs. And its maqām sometimes changed.

Let us listen to Manṣūr ‘Awaḍ, Sāmī al-Shawwā, and Maqṣūd Kalkajian playing the ṣabā version of this taḥmīla that we will not make many comments about. We will listen to this recording in between Ibrāhīm Sahlūn and Al-‘Aqqād’s recording to the bayyātī, and Sāmī al-Shawwā and Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān’s recording to the bayyātī made by Pathé. Note that, even though Sāmī al-Shawwā played to the ṣabā, he did not go far from the bayyātī version that he had surely heard and played before.

Let us listen to this ṣabā taḥmīla recorded by Gramophone around 1910…

(♩)

The bayyātī taḥmīla includes a different/particular dūlāb qafla, i.e. it is not an ordinary dūlāb qafla as it also includes another melody, or another dūlāb, played as a conclusion to the melody of the taḥmīla, and that is not included in the initial taḥmīla melody or in its ascending notes. Let us listen to this conclusion…

(♩)

This conclusion is included in both Ibrāhīm Sahlūn and Al-‘Aqqād’s recording, and Sāmī al-Shawwā and Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān’s recording. So it seems that this is the bayyātī taḥmīla in its known form, and that the ṣabā is derived from it.

Let us first listen to the version by Ibrāhīm Sahlūn and Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād since it is the oldest –it was recorded by Odeon around 1906. The Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād / Ibrāhīm Sahlūn duo was only recorded by Odeon, while Gramophone recorded them in a trio with ‘Alī ‘Abduh Ṣāliḥ. Later on, Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād played in a trio with Sāmī al-Shawwā and Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī, and Ibrāhīm Sahlūn played in a trio with Manṣūr ‘Awaḍ and ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī recorded by Baidaphon.

It seems that Ibrāhīm Sahlūn and Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād, both no longer young, had experience in playing together, as their dialogue is flowing and harmonious. It also seems that they were new to recording and their performance sometimes sounds too fast. But, in general, the recording is calm and harmonious, and includes phrases that, if not similar, express similar ideas. Let us listen to the recording of Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād and Ibrāhīm Sahlūn, made on one side of a 27cm record by Odeon around 1906…

(♩)

The recording of Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān and Sāmī al-Shawwā was made around 17 years later, in November 1923, by French record company Pathé whose recording process was different and who did not achieve great success in the Arab World, probably because the recording system of Gramophone, Odeon, Baidaphon and Polyphone was more widespread in Egypt. Pathé with their vertical system came much later, and people did not choose to buy new heads for their gramophones, just to play Pathé records. Consequently, Pathé only conducted two recording campaigns in the Arab World.

This Pathé duo was recorded with many, including Sayyid al-Safṭī, Simḥa, Badī‘a Maṣṣābnī, and Najīb al-Rīḥānī. Indeed, many recorded in this jalsa which was apparently a good thing to do. They were later joined by Zakariyyā Aḥmad who, in an interview, spoke well of Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān and Sāmī al-Shawwā who also recorded with him in Pathé’s recording campaign that includes the recording we are about to hear. The taḥmīla is on the second record-side, yet it is strongly tied to the first side, taqsīm “Shiftishī”.

The taqsīm on two chords of Sāmī al-Shawwā recorded the first side should include enthusiasm and dancing, yet it is also calm and includes salṭana that may result from Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān’s qānūn, influenced by Al-Quḍḍābī, and not by Al-‘Aqqād’s impishness. His calm performance focuses more on conveying the phrase through the number of strokes –that are not as many as Al-‘Aqqād’s, while the phrase itself is not as short as the latter’s, and his edges are very slow and calm. Sāmī al-Shawwā performs dancing phrases, yet his performance also tends towards salṭana and Ibrāhīm al-‘Aryān’s calm qānūn.

The second side is the dialogue: Sāmī al-Shawwā starts with the taqsīm. He does not play on two chords anymore, or on an octave, as he goes back to regular kamanja playing. Sill, it is relatively higher in scale than the previous recording, which encourages the qānūn to exploit its space and go down in the qarār, and thus perform more salṭana… It seems to be lower while it is in fact higher: the qānūn exploits almost 3 dīwān within its space, a rare occurrence in old recordings, as they usually tuned every dīwān of the qānūn to a maqām, and thus did not use the 3 dīwān at once. Yet here, the man is comfortable, making changes with his ‘urab, while still performing down-up picking as if he had no ‘urab, which I think he did on purpose: he was well-aware of the presence of the ‘urab, yet did not consider they should keep him from performing down-up-picking the accidental tunes with his hand… as down-up-picking has a special beauty, and Sāmī al-Shawwā exploited all the sound-types at his disposal.

Here is a call to all instrumentalists: listen to these people producing all kinds of sounds with their instruments. As instrumentalists, we should exploit to the fullest all the sounds an instrument can produce in order to play varied phrases, not only expected ones, and not only what is written in books.

Let us listen to raqṣ “Shiftishī” and the rāst taḥmīla recorded by Pathé on two sides –one side with raqṣ “Shiftishī” and the other with the taḥmīla– of a 25cm record, in fall 1923.

(♩)

Beautiful! Both recordings are marvellous! Fantastic! What else can I say? One can only feel it…

Dear listeners,

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Sama‘ ”

We will meet again in a new episode…

“Sama‘ ” was presented to you by AMAR.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)