The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Sama‘ ”.

The “Sama‘ ” show discusses our musical heritage through comparison and analysis…

A concept by Mustafa Said.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Sama‘ ”.

Today, we will analyse a bashraf ‘ushshāq composed by Al-Ṭanbūrī ‘Uthmān Bēk.

In previous episodes, we talked about the bashraf form in every detail, describing its different types and structures…etc.

We will sum up and discuss today’s bashraf made of khāna and lāzima of equal lengths: the length of each khāna and of each lāzima equals two measures of a 32-pulse’ rhythm, or a 64-pulse’ rhythm according to some, or a 16-pulse’ rhythm as mentioned in books such as Muḥammad Shahāb al-Dīn’s “Safīnat al-mulk” and Kāmil al-Khula‘ī’s “Al-mūsīqī al-sharqī”. So, the number of measures is the same in the khāna and in the lāzima.

Let us first discuss the rhythm then talk more about the maqām.

The rhythm is as follows: dum iss dum iss tak iss tak iss tak tak dum tak tak dum tak iss dum iss tak iss tak iss tak tak tak iss tak iss tak tak tak tak.

(♩) (beat)

I will define it as a 32 pulse’ rhythm, i.e. 2/4/4/3/3/4/4/4/4, knowing that each 4 is divided into 2. As mentioned in different episodes and in relation to many subjects, a rhythm’s measures are divided either into 2 or 3.

This was concerning the 16-pulse’ beat or uṣūl.

Now, concerning the maqām:

The maqām is the ushshāq, in this case the Turkish ‘ushshāq, a dūkāh sub-maqām with a scale resembling the bayyātī’s but with the pattern of a compound maqām, starting at the rāst followed by the dūkāh, then descending to the yakāh, then ascending…etc.

The Turkish ‘ushshāq is a compound maqām, and totally different from what we call ‘ushshāq and that Turks call Arabic ‘ushshāq and consider to be in the busalīk’s category. To us, the ‘ushshāq is the origin (aṣl) while to them the busalīk is the origin. … This is all just a matter of appellations, yet note that Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād played the bashraf ‘ushshāq to the Turkish ‘ushshāq, and the taqsīm ‘ushshāq to the Arabic ‘ushshāq. So they obviously knew the difference between the Arabic ‘ushshāq and the Turkish ‘ushshāq, and did not play randomly. Also, Mīkhā’īl Mashaqa mentioned that the Arabic ‘ushshāq is different from the Turkish ‘ushshāq in “Al-risāla al-shahābiyya”.

So, the bashraf is to the Turkish ‘ushshāq…

Before starting our analysis, note that the Turkish version of the bashraf is a little different from its Arabic interpretation, not in relation to the measures/rhythm such as in the case of the bashraf qarābatāk, but in relation to some notes/tones.

Let us listen, for example, to the lāzima performed by the author’s son, Jamīl Bēk al-Ṭanbūrī…

(♩)

Now, let us listen to the lāzima played by the Odeon band…

(♩)

Note the difference: the shūrī in the Odeon band’s interpretation is absent from the lāzima in the Turkish form.

Before resuming our analysis, let us listen to the full Turkish version of the bashraf –that is supposed to be the original version– performed by Al-Ṭanbūrī Jamīl Bēk and recorded by Orfeon around 1912.

(♩)

Beautiful Sī Al-Ṭanbūrī Jamīl Bēk!

The taqsīma in the conclusion is played on the “kamāntshēh”, i.e. the 3-strings’ violin we called “arnaba”, accompanied by a ṭanbūr player I do not know, and I would be grateful if anyone could provide us with the information.

What a marvellous performer… Better than a Prince!

Turkey’s Mr. ‘Abd al-Ḥalīm al-Nuwayra considers the recording we just heard as ‘Uthmān Bēk’s bashraf ‘ushshāq. The older notation by Muḥammad Hāshim is not the one followed in most Turkish recordings today.

As a proof, we have an instrumental performance older than Jamīl Bēk al-Ṭanbūrī’s by nāy player Ḥāfiẓ Tuwīk who played on a Turkish nāy –an added part, called “pāshpārā” in Turkey, can be affixed onto this nāy in order to raise the sound. We will discuss this in an episode dedicated to the nāy.

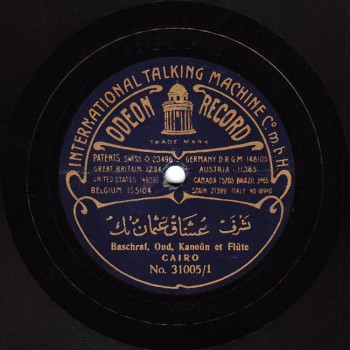

The point is that he played on a Turkish nāy in an obviously Turkish manner, accompanied by a qānūnist who lived between Turkey and Egypt, an Armenian from Turkey who came to Egypt, Maqṣūd Kalkadjian. The recording was made in Egypt during the first recording campaign of Odeon in 1903.

We will listen later to the performance of a very famous takht –that made beautiful recordings with Gramophone– recorded around 1908-9. The takht’s members are Maqṣūd Kalkadjian (qānūn), Manṣūr ‘Awaḍ (‘ūd), Sāmī al-Shawwā (kamān), and Amīn al-Buzarī (nāy).

We will listen in a little while to an excerpt from the recording of Maqṣūd and Ḥāfiẓ.

But before this, let us present the recordings of today’s episode:

the recording of Maqṣūd and Ḥāfiẓ made by Odeon in 1903 in Egypt;

the recording of the Odeon band including Ḥāj Sayyid al-Suwaysī, ‘Abd al-‘Azīz al-Qabbānī, and ‘Alī ‘Abduh Ṣāliḥ, made around one year later or more, i.e. late 1904 / early 1905;

another recording made around one year later, i.e. in 1906, of Ibrāhīm Sahlūn and Muḥammad Ibrāhīm;

–all the above-mentioned recordings were made in Egypt–.

the recording of Al-Ṭanbūrī Jamīl Bēk made by Orfeon in Turkey;

a recording made in the early 1920s around 1921, of takht Al-‘Aqqād including Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād and Sāmī al-Shawwā, made by Gramophone/His Master’s Voice;

a recording of Sāmī al-Shawwā, Muḥammad al-Qaṣṣabgī, and Muḥammad ‘Umar made by Baidaphon one year and a half later, around 1923;

and finally, the only electrical recording in today’s episode, made in Berlin-Germany at the beginning of 1928, of the Iraqi jawqa who accompanied Muḥammad al-Qubbanjī. They also recorded at the time with Ḥabība Masīka among others, and their recordings include some taqsīm and bashraf including this bashraf that proves without any doubt that they had heard Baidaphon’s recording of Sāmī al-Shawwā, Muḥammad ‘Umar, and Al-Qaṣṣabgī. The instrumentalists are: Al-‘Āzūrī (‘ūd), Ṣayūn (qānūn), and Iskandar (kamān).

These are today’s seven recordings. We will unfortunately not listen to all of them. Still, note that we have no less than five other recordings of this bashraf that is among those that were recorded a lot.

The last recording we listened to was Jamīl Bēk al-Ṭanbūrī’s full recording of the bashraf.

Let us now listen, for comparison purposes only, to an excerpt of another recording by a Turkish performer who surely took it directly from ‘Uthmān Bēk.

Here is Ḥāfiẓ Tuwīk accompanied by Maqṣūd Kalkadjian –who moved from Turkey to Egypt. Let us listen to an excerpt to confirm that the Turks, too, did not agree on a set structure, even though Ottoman music at the time had started to tend towards fixed/set elements, while improvisation was also present. Improvisation always exists in all maqām musical systems.

Let us listen to an excerpt performed by Maqṣūd and Ḥāfiẓ…

(♩)

Note the very soft qānūn and the beautiful and soft nāy including great bass.

Dear listeners, we have reached the end of today’s episode of “Sama‘ ”.

We will meet again in a new episode to resume our analysis of Al-Ṭanbūrī ‘Uthmān Bēk’s bashraf ‘ushshāq.

“Sama‘ ” was presented to you by AMAR.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)