The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Sama‘ ”.

The “Sama‘ ” show discusses our musical heritage through comparison and analysis…

A concept by Mustafa Said.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Sama‘ ”.

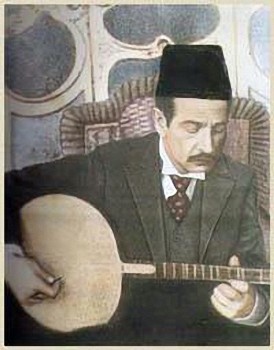

Today, we will resume our analysis of Al-Ṭanbūrī ‘Uthmān Bēk’s bashraf ‘ushshāq.

As already mentioned, the khāna and the lāzima both consist of two 32-beat’ measures.

This bashraf includes a taslīma consisting of half the second measure, i.e. if we divide it into four 16, it is the last 16, half a measure.

In the first khāna and the lāzima and the second khāna, this taslīma is as follows…

(♩)

Then, in the third and the fourth khāna, the taslīm changes and becomes as follows…

(♩)

In the first khāna, he plays to the rāst and to the nawā then ascends to the nawrūz.

In the second khāna, he plays a scale from the rāst to the nawrūz at the beginning.

We mention this to explain that this bashraf includes a taslīm performed from and to the khāna: from the khāna to the lāzima, and from the lāzima to the khāna.

Now back to the first khāna that illustrates perfectly the ‘ushshāq maqām’s scale from the beginning.

The Turkish ‘ushshāq is as follows:

The Turkish ‘ushshāq is as follows:

it starts from the rāst, goes to the dūkāh, stays there, descends to the yakāh, concludes to the dūkāh, ascends to the nawā, goes to the ‘ajam –in the Arabic ‘ushshāq, the nawrūz that is a little less than the ‘ajam, is played instead of it–, stays on the Arabic ‘ushshāq or the busalīk, then shifts back again to the dūkāh…

…such as in the lāzima that starts to the nawrūz, or the ‘ajam, and follows the same sequence… (Si la Do Si La La Sol Si La Sol Sol) …until it descends to the dūkāh.

This lāzima is the first Arabic interpretation of this bashraf: we explained at the start of this analysis about the use of the shūrī instead of the ḥusaynī in this specific position. Let us listen to it again, just to confirm this…

(♩)

Great.

In the second khāna, he shifts to a shūrī shar‘ī: he takes a ḥijāz from the nawā thus producing a shūrī maqām, not a kārjahār even though some Turkish theorists consider it to be a kārjahār… Anyhow, the point is that he takes a ḥijāz from the nawā and affirms it by using the kurdī’s jawāb as the ḥijāz’s sixth scale-step.

Let us listen to the second khāna, the taslīm to the lāzima, the lāzima, and the taslīm to the third khāna performed by Ibrāhīm Sahlūn and Muḥammad Ibrāhīm. After the lāzima, Muḥammad Ibrāhīm stops because the record-side is reaching its end and performs some beautiful taqsīm to the bayyātī’s high muḥayyar. Notice Muḥammad Ibrāhīm’s fantastic qānūn impishly ascending scales, and note that their performance is to the nawā…

(♩)

Before discussing the third khāna played to the muḥayyar, let us talk about our recordings of this performance:

Jamīl Bēk al-Ṭanbūrī plays his violin to the dūkāh;

Maqṣūd and Ḥāfiẓ play their violin to the dūkāh;

the takht of Al-‘Aqqād and the takht of Al-‘Āzūrī also play it to the dūkāh;

Sāmī al-Shawwā, Al-Qaṣṣabgī, and Muḥammad ‘Umar play it to the nawā. –Note Al-Qaṣṣabgī’s qarār to the rāst. We will highlight this again when we listen to the recording–;

the Odeon band also plays it to the nawā;

and Ibrāhīm Sahlūn and Muḥammad Ibrāhīm also play it to the nawā, as mentioned previously.

Consequently, the range is not an issue in the playing, each displays it and interprets it as one wishes.

Let us now discuss the third khāna played to the muḥayyar… the last display of the ‘ushshāq since it must ascend to the muḥayyar after that.

The third khāna in the Turkish playing system and the third khāna in the Arabic playing system are the most alike out of all the other sections: he plays the taslīm before the lāzima from the ḥusaynī to the nawrūz and goes back again to the dūkāh. In some Arabic recordings, and certainly not in the Turkish ones, the performance is to something resembling the nakrīz.

Let us listen to some Turkish playing. Maqṣūd and Ḥāfiẓ, for example…

(♩)

Let us now listen to the same part performed by Al-‘Āzūrī, Ṣayūn, and Iskandar…

(♩)

The fourth khāna is the perfect opposite of the third khāna: it is the most different section from one Arabic recording to another, and between the Arabic recordings and the Turkish recordings. It starts at the sīkāh –he shifts completely from the ‘ushshāq to the sīkāh.

Let us listen to the sīkāh performed by:

Ḥāfiẓ and Maqṣūd;

the Odeon band;

Al-Ṭanbūrī;

Sāmī;

and finally by Al-‘Āzūrī, Iskandar, and Ṣayūn who will later be named “Al-jawq al-‘irāqī al-mumtāz” (The Excellent Iraqi jawq) by the record companies.

Let us now listen to the five interpretations…

(♩)

Each play according to their mood… even the dimensions are different…. But they never disagreed to the point of fighting. It all went well.

After the sikāh, he shifts to the nahāwand using the ḥijāz as if he were playing a nawā athar, then shifts fully to the nahāwand, goes back to the jahārkāh, shifts fully to the nahāwand, descends to the yakāh using the ḥijāz as if it were playing a shatt ‘arabān, then goes back to the sikāh to conclude the khāna, followed by the taslīm of the third and the fourth khāna. It seems that he changed the taslīm specifically to this purpose so he does not have to go back to the dūkāh and perform the taslīm to the sikāh.

Let us listen to this part in Al-Qaṣṣabgī’s recording with Sāmī al-Shawwā, Al-Qaṣṣabgī, and Muḥammad ‘Umar, and notice Al-Qaṣṣabgī’s marvellous performance of the taslīm…

(♩)

Beautiful!

We have completed the analysis of the four khāna, the lāzima, and the two taslīma in between: the taslīma in the first khāna, the lāzima, and the second khāna; and the second different taslīma in the third and the fourth khāna. Still, the repetition of the taslīm between the khāna – after the third khāna and the fourth khāna– reminds us of the old taslīm, then he concludes.

Let us now listen to the full recording of Sāmī al-Shawwā, Muḥammad al-Qaṣṣabgī, and Muḥammad ‘Umar made by Baidaphon. We will notice that the percussions play to a 4/4 beat, not abiding by the full 16 and 32-pulse’ rhythmic cycle. I have no idea why… they may have been simplifying. Some say that percussionists had not memorized long rhythms, which I doubt. Others say that instrumentalists make mistakes, and that while performing ornamentations, they would go outside the long rhythm. These are opinions, and, in mine, Arab performers tend towards simplification.

Let us listen to Al-Ṭanbūrī ‘Uthmān Bēk’s bashraf ‘ushshāq performed by Sāmī al-Shawwā (kamān), Muḥammad al-Qaṣṣabgī (‘ūd), Muḥammad ‘Umar (qānūn), and maybe Muḥammad ‘Alī Li‘ba (percussions), recorded by Baidaphon around 1923. Note that this recording was published in 2015 by AMAR within a collection of Sāmī al-Shawwā’s recordings on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of his death…

(♩)

Less than five years later, electrical recording arrived. Baidaphon’s electrical recording of the bashraf made in Berlin at the beginning of the recording era clearly shows that the performers had heard the recording of Al-Shawwā, Al-Qaṣṣabgī, and Muḥammad ‘Umar. Even though Al-Shawwā, Al-Qaṣṣabgī, and Muḥammad ‘Umar played it to the nawā and those played it to the dūkāh, it is obvious that the latter had heard the formers’ recording. Also, the violinist Iskandar had heard some other recordings of Sāmī al-Shawwā where he played jawāb, and is very influenced by him while his Iraqi stamp is also present.

A remark we made before listening to this recording: note the behaved performance, the compliance with the rhythm to a certain point, and the repeated lāzima… maybe because they did not want to perform taqsīm, so they repeated the lāzima instead in order to fill the voids at the end of the record-side.

Here are Al-‘Āzūrī (‘ūd), Ṣayūn (qānūn), and iskandar (kamān) performing Al-Ṭanbūrī ‘Uthmān Bēk’s bashraf ‘ushshāq recorded by Baidaphon in Berlin in the winter of 1928…

(♩)

Dear listeners, we have reached the end of today’s episode of “Sama‘ ”.

We will meet again in a new episode to analyse another work.

“Sama‘ ” was presented to you by AMAR.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)