The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

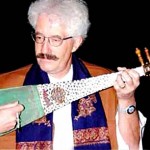

Today, we will talk about the History of Recording in Yemen with Prof. Jean Lambert, a music researcher specializing in Music in Yemen, and who, by the way, sings very well… but he does not like to talk about it.

Thank you.

Recording reached Yemen very late.

It reached Egypt 20 years after Thomas Edison invented it, a delay we consider very long, while it took even longer to reach Yemen. What is the story behind this? Before the arrival of record companies in Yemen, did anybody in Yemen record cylinders on a field research level? Or did recording start directly with the record companies?

Indeed, recording reached Yemen quite late. This shows how secluded and closed the country was as a result of religious fundamentalism and political isolation. To my knowledge, the first recording made in Sanaa in Historical Yemen was made by German orientalist and music expert Hans Helfritz who visited Yemen in the late 1920s and early 1930s in order to study Yemeni Music. I heard an excerpt from his recordings of different musical styles, including folkloric dances and songs, yet they were not published, and thus are not well known. They are kept today at the Ethnological Museum of Berlin. These recordings must be studied in order to provide us with extensive information on the History of Yemeni Music.

You told me off-the-air that there is an interesting story about this man.

Indeed. Hans Helfritz visited Yemen where he made recordings in this fundamentalist religious atmosphere, which aroused the suspicion and caution of the pious and religious in particular, and he was accused of being a spy… God knows if this is true or not. He visited Ma’rib as well as Kabyle and mountainous regions where foreigners were rarely seen, and thus came up against a lot of difficulties, and ended up jailed in Sanaa for many months after which he left Yemen and wrote a pleasant book “Al-Yaman min al-bāb al-khalfī” (Arabic title: “Yemen from the Back Door”) (English title: “The Yemen: a Secret Journey”) telling the whole story. He was fortunately and miraculously able to take the cylinders –there were neither reels nor discs yet– along with him.

Imam Yaḥya Ḥamīd al-Dīn who feared openness and foreign interference, forced the Turkish Ottomans out and defended the independence of Yemen, yet within conservative and fundamentalist restrictions. As a consequence, the Yemeni Radio was only launched in 1955.

Very late indeed.

It was a reaction to the launching of the Ṣawt al-‘Arab Radio that had started to broadcast, from Cairo, notably liberalist political ideas.

Liberalist / military.

Quite the opposite of the royal despotism in Yemen.

So Imam Aḥmad, the son of Imam Yaḥya Ḥamīd al-Dīn, who took his reign in 1948, consulted with theologians who refused the launching of the Radio. Still, the Radio was launched, and broadcasted news at first. They also recorded Qāsim al-Akhṭash, a Yemeni artist who was in Sanaa at the time. He recorded reels that existed at the time and allowed a longer recording duration. Yet recordings were made in Aden before the Sanaa Radio’s recordings: they were commercial recordings of Sheikh ‘Alī Abū Bakr Bāsharāḥīl made in the late 1930s, in 1939, by Odeon.

Upon the outbreak of WW1, German record company Odeon had to stop its commercial and recording activities as Yemen was under English occupation. Local record companies started right away, including the major “Aden Crown Company” that took over from Odeon and resumed recording Sheikh ‘Alī Abū Bakr Bāsharāḥīl, as well as Sheikh Ṣalāḥ ‘Abd al-lāh al-‘Antarī and Sheikh Muḥammad al-Mās.

Muḥammad al-Mās was still alive?

Yes. Al-Mās and Bāsharāḥīl died in the 1950s. They had recorded with the Aden Crown Company in the 1940s.

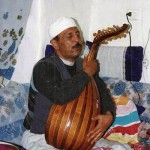

But Ibrāhīm al-Mās continued.

Ibrāhīm al-Mās, the son of Muḥammad al-Mās, continued. But he did not play the qanbūs as he went directly to the oriental ‘ūd called kabanj ‘ūd in Yemen, a local appellation derived from kamān –i.e. the violin, not the ‘ūd. Kamanja became kabanj.

Ibrāhīm al-Mās became famous for singing accompanied by the kabanj and recorded more than 150 or 200 songs with the Aden Crown Company as well as with minor record companies, such as Jaafarphone among other record companies in Aden in the 1940s.

But Ibrāhīm al-Mās sometimes sang with a violin. He had his ‘ūd with him, and the violin was there too.

Yes. Bāsharāḥīl also had a violin with him sometimes.

So, recording in Yemen started with Odeon, even though the English were present in Aden long before. But Gramophone did not record, right?

Right. Gramophone did not record.

Did any Yemeni muṭrib record outside Yemen before that?

It seems that artists from Ḥaḍramūt who lived in Indonesia and in India recorded in these countries. But we still unfortunately do not know when these recordings were made. Obtaining these recordings made by Indian and Indonesian record companies will undoubtedly require a lot of work.

I saw many Yemeni labels in India by Gramophone India.

Yes, Gramophone does exist in India.

Then this would allow us to determine the recording date, down to the month of recording.

Yes, but it will be strenuous.

Sheikh Muḥammad al-Bār recorded in Indonesia.

In India, I heard Qur’ān psalmodizing, but I did not hear Yemeni artists. Still, I think there are some.

Let us listen to something by Sheikh Muḥammad al-Bār…

(♩)

Beautiful.

What shall we listen to from the early commercial recordings made in Yemen, since the special recordings or the research recordings are still unfortunately unavailable/unaccessible?

There is a wide choice… Let us listen to Sheikh ‘Alī Abū Bakr Bāsharāḥīl recorded by Odeon…

(♩)

Muḥammad al-Mās recorded at the same time as Sheikh ‘Alī. The Al-Mās family was a family of musicians, wasn’t it?

The Al-Mās family were artists, including Muḥammad al-Mās and his son Ibrāhīm, as well as ‘Abd al-Raḥmān al-Mās –of Ibrāhīm’s generation, maybe his cousin– who recorded at the time. I do not know if there were artists in the family before that.

We mentioned that names weren’t known because of the religious fundamentalism in Yemen.

Yes, it is difficult to confirm.

Let us listen to something by Sheikh Muḥammad al-Mās…

(♩)

Ibrāhīm al-Mās changed the instrument but not his father’s style, or did he?

Changing the instrument undoubtedly affected the style: there is a big difference between Ibrāhīm al-Mās and his father.

There is one song that they both recorded, which provides an opportunity for comparison, showing some difference between Ibrāhīm and his father Muḥammad: the ‘ūd accompaniment of the voice is different, since the oriental ‘ūd does not abide by the accents and tones specific to the Yemeni ‘ūd that accompanies the voice rather slowly, especially with Muḥammad al-Mās and Abū Bakr Bāsharāḥīl… There is not a lot of finger picking, while the oriental ‘ūd, especially with Ibrāhīm, includes such finger picking.

A continuous picking.

Moreover, the Yemeni ‘ūd includes leaps that do not exist in the oriental ‘ūd.

This is concerning playing. I said that he changed the instrument. But now I am talking about the voice, the singing… Is there a big difference?

The singing is also a little different… not very different, but it is considered different nonetheless.

Did Ibrāhīm al-Mās become softer than his father?

Yes. Especially that the old recordings did not include solo ‘ūd playing, unlike the later recordings.

Ibrāhīm al-Mās was influenced by Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb whom he met in Aden. He liked Egyptian songs, some of which he sang and recorded.

Indeed, we have a recording of dawr “Matti‘ ḥayātak” in his voice, in Yemeni.

Yes.

Let us listen to something in Yemeni by Muḥammad al-Mās, then we will listen to “Matti‘ ḥayātak” (that is not by Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb).

Let us listen to Ibrāhīm al-Mās singing “Al-‘uwaydī naẓam”, an important song because it is a muwashshaḥ including the 3 parts that constitute the Yemeni muwashshaḥ. The author of this old muwashshaḥ is unknown…

(♩)

Dear listeners, we have reached the end of today’s episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

We thank Prof. Jean Lambert for his presence with us in today’s episode.

We also thank Mr. Ahmad al-Salihi who helped us collect the recorded material for today’s episode.

Note that numerous recordings in this episode are from the private collection of the great Sheikh Khālid Āl Thānī, who honoured us with his generosity and lent us the recordings we wanted from his record library.

We will meet again in a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”

“Min al-Tārīkh” was brought to you by Mustafa Said.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)