The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

Today’s episode is about the “Sulṭāna”.

“Sulṭānat al-ṭarab”.

Sitt Munīra!

Our guest Prof. Frédéric Lagrange, without whom this show would have never seen the light, will be telling us about her. Good morning Sir.

Good morning.

“Sulṭānat al-ṭarab”… Today, the name Munīra al-Mahdiyya remains a legend in Egypt, throughout the Arab World, and in the Middle-East. It is linked, in the imaginary of journalists and in the Arab collective unconscious to an era during which people drank champagne in the shoes of muṭriba and lit cigars with banknotes. These nonsensical clichés, probably born from the years between WW1 and WW2 in America and in Europe, hide the scarcity of the information about “Sulṭānat al-ṭarab” Munīra al-Mahdiyya.

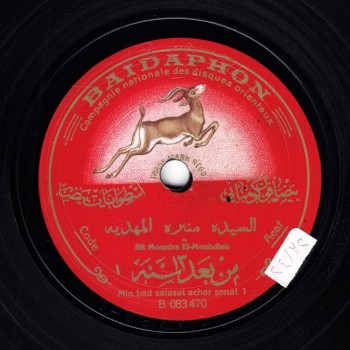

Our sources include Prof. Ratība al-Ḥifnī’s book written in 2001 –long before she died. The beginning of the section dedicated to the life of Munīra al-Mahdiyya includes a pleasant anecdote that I will read and that I think we must discuss. Ḥājja Ratība says: “At the beginning of her artistic journey, Munīra al-Mahdiyya recorded with Baidaphon a collection of songs that were not appreciated by the public. Later on, when her fame grew and she was nicknamed “Sulṭānat al-ṭarab” and people started buying her discs, Baidaphon redistributed her old recordings at a higher price to make more money. It is said that she went, disguised in a milāyat al-laff (full-body garment), to the record company where she met with the owner Mr. Buṭrus Jubrān Baiḍā whom she asked: “Do you still have Munīra al-Mahdiyya’s discs?” He answered laughing: “Of course”. She asked him to bring them all, so he thought she was a fan who wanted to buy Munīra al-Mahdiyya’s discs. The employee came carrying a box full of discs. Munīra asked him if these were all the discs he had, and after he said yes, she very quickly threw them on the floor and broke them all, then, before he got angry, gave him a large amount of money to make new recordings with her now mature voice. Only then did Mr. Baiḍā discover her real identity and he said: “Disguised in milāyat al-laff, you look like Rayyā and Skīnā”. This hardly credible story ends here.

Weren’t Buṭrus and Jubrān brothers?

They were indeed. There was no Buṭrus Jubrān Baiḍā… but this is a detail. The point is that Munīra al-Mahdiyya’s old Baidaphon discs recorded around 1914 and whose numbers start with 23 still exist. Moreover, two other companies recorded Munīra al-Mahdiyya’s voice during this same phase.

Zonophone and Odeon, as well as Bekka.

Exactly, Zonophone, Odeon, and Bekka.

Munīra al-Mahdiyya, the‘ālima, had already recorded long before.

Now, whether this story is totally invented or not, it still bears some truth relatively to her dissatisfaction with her old recordings made when she was a ‘ālima. More importantly, this story indicates that there were in fact two Munīra: the pre-1920s Munīra and the post-1920s Munīra, i.e. Munīra the ‘ālima and Munīra the muṭriba. The real riddle lies in her transformation from a ‘ālima into a muṭriba: she is among the very few who achieved this evolution, this total transformation, on the reputation level, as well relatively to the maturity of her voice, her vocal ability, and her smart performance.

True. Now, what if we applied the same story to Asma al-Kumthariyya? I am referring to the vocal ability and to dealing with the melody. This is not about someone performing the repertoire of ‘ālima, it is about someone achieving a fantastic performance of dawr.

Thus, we must go back to our previous episodes where we defined the difference between the two types of ‘ālima: the ‘ālima in the true sense of the word, i.e. the learned ‘ālima, and the ‘ālima who only sang a female repertoire at weddings. Asma al-Kumthariyya, or Sitt al-Lawandiyya who unfortunately did not record, are among the 19th century ‘ālima, when muṭriba and ‘ālima were one and the same. Whereas, in the 20th century, the path of a ‘ālima and that of a muṭriba were distinct, and thus the term ‘ālima had another connotation: muṭriba sang a high-standard repertoire for high-class audiences, while ‘ālima were mundane muṭriba –not baladī singers– whose repertoire consisted exclusively of female wedding songs, mostly ṭaqṭūqa, Egyptianized Aleppan qadd, or Aleppanized Egyptian ṭaqṭūqa.

So, Munīra al-Mahdiyya is a symbol of this transitional period, and may be the one who changed the name of dawr-singing ‘ālima to muṭriba.

Exactly…

(♩)

Some sources claim that Munīra al-Mahdiyya was born in Zaqāzīq and that her name was Zakiyya Manṣūr Ghānim, while others claim that her name was Zakiyya Ḥasan. In this respect, I think we can believe Ratība al-Ḥifnī who conducted her research on Munīra al-Mahdiyya in the 1920s written media, including some press interviews where Munīra al-Mahdiyya allegedly declared that she was born in 1885 in a modest family in the Mahdiyya village under the jurisdiction of al-Ibrāhimiyya in the Sharqiyya Governorate. We can confirm that she was born between 1885 and 1888.

Ratība al-Ḥifnī adds that historians do not agree on her place of birth: in an interview published in a 1927 issue of the magazine “Al-Masraḥ”, Munīra al-Mahdiyya allegedly stated that she grew up in Alexandria where she lived supported by her sister. It is not clear whether she was born in Alexandria or not. On the other hand, she made no mention of her early childhood in Mahdiyya, and did not mention either if she was born there.

The real name of Munīra al-Mahdiyya was Zakiyya Ḥasan Manṣūr. And we can confirm that she grew up in Alexandria.

This book also mentions the memoirs of Munīra al-Mahdiyya written by Munīr Muḥammad Ibrāhīm, that state that she was already famous as a child for her beautiful and pure voice, and that she used to sing for her friends as well as in villages and towns surrounding Hahiyā… where?

In Sharqiyya.

Her fame grew in Sharqiyya, and she went to sing in Zaqāzīq the capital of the muḥāfaẓa (Governorate).

One day, Muḥammad Faraj, owner of a club in Cairo, heard her sing in Zaqāzīq. He is the one who discovered the power and the beauty of her voice and seduced her!

I don’t understand!

He seduced her with the promise to make her famous in Cairo where she started off by performing in a café managed by him in 1905. This information almost coincides with the approximate chronicling of her first recordings made between 1905 and 1907 by Zonophone and Odeon.

Yes. It seems that she recorded with Zonophone before Odeon in 1905.

Munīra admired the voice of muṭriba al-Lawandiyya –mentioned in Sāmī al-Shawwā’s memoirs, and who unfortunately did not record – and often crept among the guests in the Sarādiq to listen to the voice of this muṭriba whom she imitated. I have doubts in this regard… She was already 20 and was certainly not forced to creep inside.

This 20 years’ old young girl started attracting admirers with her deep, magical and warm voice. Soon, everybody had heard about her and more people were visiting the “Theatro” where she sang. The authorities tried to stop her from singing because she was still a minor.

Difficult!

Again, this is very difficult.

The day Munīra al-Mahdiyya sang, the little café located at the intersection of Bāb al-Sha‘riyya and Azbakiyya became one of the most famous cafés in the Egyptian capital, attracting ṭarab singers and amateurs from everywhere led by the period’s song and art masters such as Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī, Sulaymān Qurdāḥī, and Salāma Ḥigāzī. We are referring to the period from 1905 to 1910 when Munīra al-Mahdiyya started feeling cramped and went to sing at the El-Dorado club where her fame grew further. She had married Maḥmūd Bēh Jabr whom she had appointed as her manager, and whom she suffered a lot with: it is said that she extended her tour in the Levant to stay away from him. They got divorced around 1923, and she recorded her famous ṭaqṭūqa “Min ba‘d talat ‘ashr sana” that we can listen to…

(♩)

Ratība al-Ḥifnī says: “After this continuous success –around 1910-11-12–, Munīra rented a café in Azbakiyya which she furnished luxuriously and named “Nuzhat al-Nufūs”, and which soon became famous as the gathering spot of artists, intellectuals and thinkers, added to the elite of society, notables and major businessmen, who met there daily. No other café in Egypt was as famous as “Nuzhat al-Nufūs”, to such a point in fact that the British authorities had to acknowledge its special status and allowed only this café to resume its work as usual, after they had decided to close down all the cafés and gathering places upon the start of WW1 in 1914.

As a consequence of the British Protectorate declared upon Egypt in 1914.

Exactly.

Let us stop here and listen to the voice of Munīra al-Mahdiyya in this first phase of her artistic journey, when she was still a ‘ālima and recorded, as mentioned earlier, with Zonophone, Odeon, and Baidaphon between 1914 and 1916… though we doubt she recorded beyond 1915 because of WW1.

In his memoirs, Sāmī al-Shawwā stated that nobody in Egypt recorded during WW1, except for Gramophone and Meshian of course.

Except for Gramophone and Meshian.

He says that Gramophone recorded 600 discs during a recording campaign in 1916, and that the sound engineer arrived by submarine… according to Sāmī al-Shawwā.

Great! What a beautiful submarine story!

The repertoire recorded by Munīra al-Mahdiyya with Baidaphon, Odeon, and Zonophone is, in part, very similar to what Bahiyya al-Maḥallawiyya recorded. She actually imitated Bahiyya al-Maḥallawiyya in the overture of the recordings, i.e. in “Beautiful, famous Sitt Bahiyya al-Maḥallawiyya! Beautiful Sī Tawfīq!”… We can hear the exact same words but with Sitt Munīra instead of Sitt Bahiyya.

Or “Yā usṭa Munīra”

Or “Yā usṭa Munīra”… “Usṭa Munīra”, or “Sitt Munīra”. Sitt Munīra does not refer to her being Maḥmūd Jabr’s wife, i.e. Sitt does not imply Mrs. I suggest we listen to a compilation of these ‘ālima songs that she recorded at her beginnings, such as “Khallīk ‘ala ‘ōmī yā mōg el-baḥr”, or “Yamma el-gada‘ dah mnēn”…

(♩)

Dear listeners, we have reached the end of today’s episode of “Min al-Tārīkh”.

We thank Prof. Frédéric Lagrange.

We will meet again in a new episode to resume our discussion about Sitt Munīra al-Mahdiyya.

“Min al-Tārīkh” is brought to you by Mustafa Said.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)