The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Sama‘ ”.

The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Sama‘ ”.

“Sama‘ ” discusses our musical heritage through comparison and analysis…

A concept by Mustafa Said.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Sama‘ ”.

Today, we will discuss and analyse tawshīḥ (improvised responsorial parareligious vocal form to a binary rhythm) “Mā shamamtu al-ward” excerpted from a qaṣīda (classical poem) written by Ḥasan bin ‘Abd al-Ṣamad al-Juba‘ī who, if my memory serves me right, was born late in the third decade of the 16th century, lived in the Levant in the Beqā‘ Valley and died probably in Persia, and composed by Sheikh Zakariyyā Aḥmad –this is the melody we will tackle–.

The tune includes six verses:

Mā shamamtu al-warda illā zādanī shawqan ilēk

Wa-idhā mā māsa ghuṣnun khiltuhu yaḥnū ‘alēk

Lastu adrī mā lladhī qad ḥalla bī min muqlatēk

Rushiq al-qalbu bi-sahmin qawsuhu min ḥāgibēk

In yakun gismī tanā’a f-al-ḥasha bāqin ilēk

Inna dā’ī wa-dawā’ī yā ḥabībī fī yadēk.

The ‘arūḍ (Arabic prosody) are to the baḥr (meter of a couplet) al-ramal “fā‘ilātun fā‘ilātun”, the tawshīḥ was composed to the sikāh –we will explain this later–, and the melody we will tackle –as there are many– is by Sheikh Zakariyyā Aḥmad.

This tune was first recorded electrically by Odeon in the 1920s, most probably in 1928, in the voice of Sheikh Ibrāhīm al-Farrān. To my knowledge, there is no earlier recording of this tawshīḥ.

We have explained that the tawshīḥ is initially a collective work with an individual performing tafrīd (improvisation) within its parts: Sheikh Ṭaha al-Fashnī, for example, added verses such as “ In dhātī wa-ṣifātī yā ḥabībī bēn yadēyk” or “Kullu ḥusnin fī al-barāyā fa-huwa mansūbun ilēk”.

Lyrics are often added to these verses. As for the melody, there is an infinite number of melodies, as this tawshīḥ was sung by several persons, by several Sheikhs…

We selected 4 recordings each of which conveys a certain message and a certain atmosphere. All the other recordings remain within the same frame.

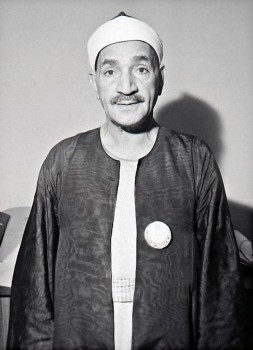

- Our 1st recording is in the voice of Sheikh Ibrāhīm al-Farrān accompanied by a takht including Sāmī al-Shawwā, ‘Abd al- Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī, and Shaḥāta Sa‘āda, and a biṭāna including Sheikh Zakariyyā Aḥmad, others I do not know, and Maḥmūd Raḥmī (percussions).

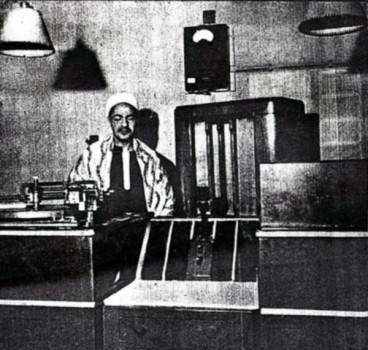

- Our 2nd recording was made twenty years later by the Egyptian Radio in Mūlid al-Mursī Abū ‘Abbās in the voice of Sheikh Ṭaha al-Fashnī, copied from Mūlid al-Mursī Abū ‘Abbās in Alexandria. We will note that this recording also includes the public.

- Our 3rd recording was made ten or fifteen years later, I do not know for sure… Sheikh Ṭaha al-Fashnī’s voice sounds older… It was most probably made in the early or mid 1960s. We would be very grateful if someone can tell us the exact date of this great recording that was probably made by the Holy Quran Radio in Cairo in the mid-1960s, in a closed space, i.e. a studio.

- Our 4th recording was made around fifteen years later, most probably in the late 70s or early to mid 80s in the voice of Wadī‘ al-Ṣāfī, may all the dead rest in peace.

Now, before we start our analysis…

We always describe the tawshīḥ as a collective form, while we always play full tawshīḥ-s. This time, I cut this tawshīḥ out of Ṭaha al-Fashnī’s 1960s recording, and now have a full one minute and forty seconds’ tawshīḥ performed solely by the biṭāna. Let us listen to this tawshīḥ form free from any repetitions …

(♩)

As we have noticed, the tawshīḥ consists of five long phrases allowing several modulations:

- The 1st phrase –the only one made of two verses “Mā shamamtu al-warda illā zādanī shawqan ilēk / Wa-idhā mā māsa ghuṣnun khiltuhu yaḥnū ‘alēk”– stops at the maqām’s fundamental position: it starts to the sikāh, a sikāh shāmī or sikāh ḥalabī as per Mīkhā’īl Mashāqa’s categorization, followed by a sikāh ‘irāq, and ends with a sikāh maṣrī as categorized by Mīkhā’īl Mashāqa … All these are different forms of one note. The point is that he uses a wide variety of sikāh types in just one phrase …

(♩)

- In the 2nd phrase –the musical phrase and not the line of poetry or the verse, since the first phrase for example includes two verses and the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th phrases include one verse only. There are six verses but only five musical phrases– “Lastu adrī mā lladhī qad ḥalla bī min muqlatēk”, he modulates to the ‘ushshāq at the fundamental position’s sixth. Yet the ‘ushshāq type is the muttaṣil (continuous) type, not the munfaṣil (discontinuous) type, i.e. at the qarār (low notes. bass) … (♩) … not at the jawāb (high notes. treble), i.e. the “brother” type (v/s the “original” type) as per the old categorisation …

(♩)

- In the 3rd phrase, he seems on the verge of performing to the bayyātī at the fundamental position’s seventh, yet he descends again to the sikāh’s fundamental position …

(♩)

- In the 4th phrase, he modulates to the rāst at the jawāb at the maqām’s sixth, i.e he performs the rāst at the same scale step at which he performed the ‘ushshāq, yet this time in the “original form”, i.e. the muttaṣil type, a rāst aspect with a rāst aspect, and reaches the peak of the tawshīḥ … (♩) … It is all in the jawāb! Let us listen …

(♩)

- In the 5th phrase –in the end or return– “Inna dā’ī wa-dawā’ī”, he seems on the verge of modulating to the bayyātī whose sub-maqām is the ‘ushshāq, then ends with the sikāh in its ordinary form, i.e. a sikāh aspect with a sikāh aspect. He modulates from the bayyātī to the sikāh the same way he had ended to the ‘ushshāq earlier, i.e. … (♩) … All this is to the bayyātī, the same way he had ended to the ‘ushshāq… then concludes with “yā ḥabībī fī yadēk”. Let us listen to it …

(♩)

Before we tackle the details of the tafrīd (improvisation) in our tawshīḥ, let us point out that the tawshīḥ form is among the forms that have the largest variety of connotations, i.e. the lyrics can either be understood as ordinary love talk, virtuous love talk, as Sufi meditation, or as a religious text.

- In the first recording, Ibrāhīm al-Farrān kept it neutral: he did not say anything at all. He sang it without giving it any specific connotation.

- Unlike Ṭaha al-Fashnī who gave it a fully religious connotation “Yā rasūl al-Lāhi ḥaqqan anā mansūbun ilēk”. He sang it from a clear and direct religious perspective.

- Wadī‘ al-Ṣāfī’ interpretation is far from that of a tawshīḥ, i.e. he dealt with it as if with a love song, like the songs popular in the 70s and 80s, especially in the Levant …

(♩)

This same issue is reflected on the tafrīd (improvisation):

With Sheikh Ibrāhīm al-Farrān for example. Here is the first tafrīda …

(♩)

Such a free interpretation! It includes almost two dīwān-s (octave)… one tafrīda with two dīwān-s.

Now, let us listen to Sheikh Ṭaha al-Fashnī’s Radio studio recording …

(♩)

Beautiful harmonious and ornamented improvisation!

The difference between this improvisation and the improvisation of Ibrāhīm al-Farrān is that the latter abides by the rhythmic cycle: most of the pulses of his tafrīd remain within the rhythm that he soon goes back to whenever he leaves it. …Unlike this completely free improvisation performed without a takht, free from music and from any rhythmic cycle. Most of his tafrīd-s are outside the rhythmic cycle. The performance includes taslīm (bashraf or samā‘ī ritornello) and tasallum from the biṭāna (accompanying singing ensemble) and the munshid (chanter. singer) as usual in tawshīḥ-s.

This recording of a live performance was made around fifteen years earlier …

(♩)

His voice sounds younger and, moreover, there is a clear interaction in this first tafrīda… Words can’t describe the difference between the feeling conveyed by a studio performance and that of a live performance among people, especially among first grade sammī‘a (listeners) –not ordinary people– in Mūlid al-Mursī Abū ‘Abbās in the 40s and 50s.

Let us listen now to Wadī‘ al-Ṣāfī …

(♩)

He ended his phrase and performed layālī in the usual Levantine manner, i.e. with a continuous rhythmic cycle while only he improvises freely. So he sings freely outside the rhythm, not abiding by the continuous rhythmic cycle that accompanies his singing and must be there because people need to hear it. We will discuss this in detail when we talk about the details of improvisation, i.e. about each tafrīda.

Let us end today’s episode with the first recording of this tawshīḥ in the voice of Sheikh Ibrāhīm al-Farrān accompanied by the takht we described earlier and dated back to the late 1920s, in 1928. Here is tawshīḥ “Mā shamamtu al-ward” written by Sheikh Ḥasan bin ‘Abd al-Ṣamad al-Juba‘ī and composed by Sheikh Zakariyyā Aḥmad.

We will meet again in a new episode of “Sama‘ ” to resume our discussion about tawshīḥ “Mā shamamtu al-ward”.

Here is Sheikh Ibrāhīm al-Farrān accompanied by his biṭāna and the takht …

(♩)

“Sama‘ ” was presented to you by AMAR.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)