The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Today we will resume our discussion about Folk Music in Lebanon with Father Dr. Badih el-Hajj.

Welcome.

Hello Mr. Mustafa.

We ended our last episode with the ‘atāba (folk monodic song in colloquial Arabic).

Let us talk today about another type of music: the long song that relies on the mawwāl (poem in colloquial Arabic, sung in a non-metrical cantillatory form) and on the sung qaṣīda-s (monometric and monorhyme poem in classical Arabic), and that is called shurūqī (traditional Bedouin melismatic threnody performed by a soloist) in literary Arabic and shrū’ī in colloquial Lebanese (“q” becomes “ ’ ”).

The origin of the appellation is oriental, and this song type originated in Eastern Lebanon.

It initially came from Iraq, as stated by the poetry, history, and music studies conducted in relation to this song type.

Let me explain why most styles originated in Iraq: Iraq is among the regions that welcomed numerous ancient civilisations. Furthermore, the Bedouin tribes that inhabited the region went to Iraq, especially during the hot seasons in the Arabian Peninsula. They took refuge on the riverbanks, mainly the Tigris and the Euphrates, in Northern Iraq and Northern Syria, and left us a significant literary, poetic, and musical heritage. It reached us through Syria, via the Bekaa, and is very present in the Bekaa region as well as in the Lebanese Mountains.

The shurūqī is a long song based on the sung qaṣīda, differentiated from Lebanese heritage and folk song and poetry by its poem’s structure whose language is closer to literary Arabic on the one hand and to the Bedouin language on the other hand.

A lahja bayḍā’ (white dialect).

Yes.

The Lebanese can understand it when it is sung in literary Arabic. Some decide to sing it “‘a-el-biddēweh”, an expression that means “in a Bedouin singing style”, reciting the qaṣīda in a Bedouin style that is considered as the origin of shurūqī singing.

The shurūqī was performed by poets during poetry duels and contests: one would recite a shurūqī verse and the other would reply with another one. These duels were conducted during evening gatherings in the Lebanese villages and towns, in happy celebrations, or upon sad events, which of course determined the type of shurūqī that was performed. Heritage singing always reflects the situation.

It was also sung in wartime, was it not?

Yes it was. They sang shurūqī about the feats of war, dedicated to a hero or a martyr. In zajal concerts in Lebanon, zajal bands still compete with shurūqī until today, knowing that the poet must master it completely because its structure and singing are much more difficult than those of qerradeh, muwashshaḥ baladī, or mu‘anna. Musically, the shurūqī is usually to the maqām (modal key) sikāh and huzām sub-maqām, i.e. to two jins (set of notes forming the basic pattern in Arab music): sikāh, i.e. E half flat then F, G, followed by the ḥijāz, i.e. G, A flat, B natural / C, and up to the octave E half Flat. Initially, in heritage music, the maqām does not change. Yet recently, the person performing mu‘anna, shurūqī, qaṣīd, or ‘atābā, sometimes varies the maqām, influenced by the Arab music that has reached us, or simply acting upon his wish to diversify. We must bear in mind though that the maqām does not change in one music type piece.

Is the shurūqī, as a poem, composed to one baḥr (poetry meter) or more?

The shurūqī poem is to one baḥr / measure. I prefer to use the term “measure” instead of “baḥr” as the latter refers us to the baḥr-s khalīl. In relation to heritage singing in the Near East or Levant regions and countries, some state that all folk music and poems were to the baḥr-s khalīl but, with time, became weaker, were disfigured, until they became a folkloric / literary mix. While others state that they were initially composed to specific measures unrelated to the 16 baḥr-s khalīl. Therefore, I use the term “measure” instead of “baḥr” to avoid any confusion. The qaṣīda has a rhyme and is to one measure, unlike other poems under the Syriac influence that do not have one rhyme, just like Syriac poems. Whereas the shurūqī has one rhyme that determines the quality of the poem, and a measure that is the same in all the poems. Some recite the qaṣīda without melody, since it is a qaṣīda at the end of the day.

Are there audio samples of shurūqī that we can listen to?

Of course there are.

Here is one of Muḥammad al-Sayyid, a semi-nomadic Bedouin from the Lebanese Bekaa region …

(♩)

Here is Khalīl Farḥa who sang shurūqī in Qā‘ in North Eastern Bekaa …

(♩)

Here is a sample by ‘Alī Ḥlayḥil, the famous singer of Lebanese heritage songs in Baalbeck, that illustrates how shurūqī is performed today, namely in Baalbeck …

(♩)

Dear Sir. What will we talk about after the shurūqī?

After the shurūqī, I will discuss the mawwāl baghdādī to illustrate the ability of the Lebanese to adapt with mastery and excellence even to recently imported styles. This style became very widespread at a certain point in time, especially in Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. It is not among the heritage folk styles, but is rather a learned singing style requiring a capable singer with a beautiful voice and a wide vocal range covering more than one octave. Also, note that its singing includes a change of maqām.

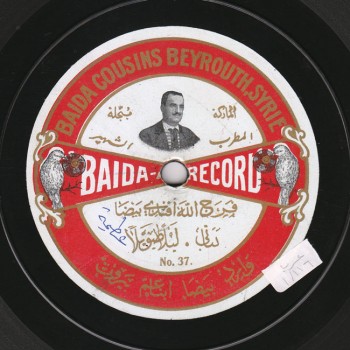

The Lebanese are very famous for singing it… Going back in history, in the Orient, the Baiḍā family with Farjallāh Baiḍā and Iliyyā Baiḍā started recording it and established their company in order to record this song type, and mainly the mawwāl baghdādī that became part of the Lebanese heritage, listed among Lebanese singing styles. This style mastered by the Lebanese existed however before the Baiḍā family, yet they are those who recorded it and excelled in singing it, and thus contributed to its fame. Being among the difficult singing styles, very few people still perform it in Lebanon. It is not sung in popular celebrations such as zajal concerts, duels, or evenings, and not even by the mutrib-s who perform shurūqī, mu‘anna and qaṣīd on stage. Nobody sings mawwāl because the structure of the poem and its performance are difficult. Instrumentally, it must be accompanied by a musical band…

…by takht instruments, not by folk music instruments.

Heritage folk music instruments whose scale is limited can’t accompany the mawwāl baghdādī that requires musical instruments with a wider scale.

The smallest band that accompanied it included only a ‘ūd and a qānūn…

(♩)

A ‘ūd (lute), a qānūn (zither), and also a percussion instrument as there are some muwaqqa‘a (metrical. measured) parts.

Shall we listen to a sample of mawwāl baghdādī?

Yes. We have a sample by Iliyyā Baiḍā whom we mentioned earlier and who sang mawwāl baghdādī extensively. But I chose the following qaṣīda …

(♩)

Dear listeners,

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Durūb al-Nagham” presented with Father Dr. Badih al-Hajj.

We will meet again in a new episode to resume our discussion about Folk Music in Lebanon.

“Durūb al-Nagham”.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)