The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

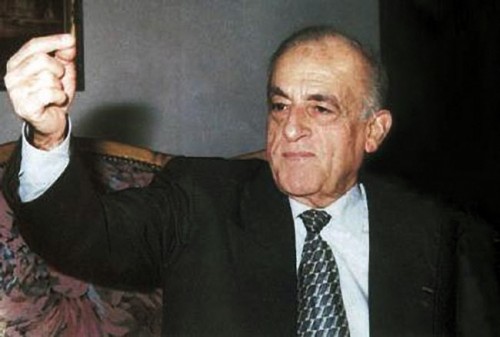

Today we will resume our discussion about Folk Music in Lebanon with Father Dr. Badih el-Hajj.

We have finished talking about the mawwāl (poem in colloquial Arabic, sung in a non-metrical cantillatory form) baghdādī. Let us discuss another form.

Let us discuss a new category of heritage singing in Lebanon: the rhythmic song that is based on rhythm rather than on the sung qaṣīda (monometric and monorhyme poem in classical Arabic) accompanied by a rabāba (spike fiddle whose front is covered with sheepskin). Which brings us back to the Bedouin origin: to the present day, Bedouins sing qaṣīda-s accompanied by a rabāba. The poet of the tribe always plays the rabāba while singing his qaṣīda-s.

The following depicts the distinction between rhythmic singing and long singing: Authentic Bedouins neither sing, dance, nor dance dabka (modern Levantine Arab folk circle dance of possible Canaanite or Phoenician origin, performed in Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Hatay, and Northern Saudi Arabia). To them, singing implies exclusively qaṣīda singing. Today, in the desert of Damascus and Iraq, the authentic pureblood Bedouin tribes –Ṭayy, ‘Niza, Shammar– only have four song types: the ‘atābā (folk monodic song in colloquial Arabic), the suwayḥilī, the nāyil, and the qaṣīd. The other tribes dwelling in suburbs are influenced by the traditions of the country they are in and thus sing and dance like its inhabitants. The measure of rhythmic songs that are segmented into syllables is based on Syriac poems. This song type is found in Lebanese mountains, especially in Mount Lebanon that had remained somewhat autonomous during the 402 years’ Ottoman Empire under which the region was divided into provinces and vassal states. So it attracted those seeking freedom and therefore wanted to preserve their homeland, heritage, and language, i.e. the Lebanese dialect that is a mix of Arabic and Syriac, thus creating this beautiful, mostly joyful –and very rarely sad– singing that accompanies weddings and celebrations.

The song forms include the qerradeh, or erradeh in Lebanese (“ ’ ” or “ e ” instead of “q”): As we mentioned in our first episode upon discussing Ephrem the Syrian, the poetry measure of the qerradeh is the “Ephrami” measure, i.e. Ephrem the Syrian’s measure based on two 7-syllable’ hemistiches, i.e. 7 / 7. The song –often heard in Lebanon– “ ‘Ala l-mānī ‘a-l-mānī” illustrates this: the 7-syllable hemistich “ ‘Ala l-mānī ‘a-l-mānī” is followed by another 7-syllable’ hemistich “Ḍarabnī w-riji‘ bakkānī”, totaling 7/7/7/7. Or the song “ ‘A el-‘mayyim ‘a-el-‘mām ṭīr we-‘allī yā ḥamām”, totalling 7/7/7/7. The poetry structure does not follow literary Arabic, i.e. the long and the short vowels, the vowel mark and the non-vowel mark. The words are pronounced in such a way as to reach an equal number of syllables to facilitate the singing / reciting. Note that speaking Lebanese sometimes sounds like reciting a qerradeh whose poetry structure is very simple.

You mean that it neither includes mudūd (extending. stretching) nor iqṣār (shortening).

Exactly. The number of syllables is the same, as in old Latin poetry or European poetry: in French poetry for example, a verse includes 4, 5, or 6 syllables. Arabic is influenced by Syriac (see Ephrem the Syrian) whose structure is found in the Lebanese mountains, especially in the qerradeh whose melody is to the sikāh (♩).

Even in the structure of the melody, the steps are close: There is no leap to the 3rd, the 4th, or the 5th. There is also the three tone E F G G F E… that we never need to change. Moreover, we recite it as if we were talking, i.e. “ ‘A el-‘mayyim ‘a-el-‘mām ṭīr we-‘allī yā ḥamām”. Yet we can also sing it as follows (♩) …

(♩)

Anybody can sing it, even a group. It is easy to sing, unlike solo singing. Whereas a qaṣīda, as a long song, requires a qaṣīda poet / singer with a beautiful voice chosen by the clan or the group to recite a verse of ‘atābā. No one would ask a person with an ordinary voice to sing ‘atābā or mawwāl baghdādī. Whereas qerradeh, as a folk tune, can be sung by anybody and by a group. The qerradeh poem is composed of 4 hemistiches, i.e. 2 verses, and usually includes a lāzima (chorus) repeated by the group and a dawr (semi-composed metric song in colloquial Arabic, sung by the lead-singer and the choir, inclusive of responsorial sections) whose lyrics address a specific situation, and that is interpreted by a soloist and repeated after him by a group. The qerradeh is an important element of the Lebanese zajal category, i.e. zajal concerts, circles, on stage performances, and duels, thanks to its easy performance, simple structure, and compatibility with any chosen topic, usually a happy one, as it is performed in joyful situations rather than upon a sad event.

Let us play a qerradeh by Joseph al-Hashem nicknamed Zaghlūl al-Dāmūr (Sqab of Dāmūr). This Lebanese zajal poet has accompanied the beginnings of zajal concerts from the days of Shaḥrūr al-Wādī (Blackbird of the Valley, i.e. As‘ad al-Khūrī al-Fighālī) up until today.

I chose him because his performance of qerradeh is very clear and we can hear the raddīda (repeaters) repeat the lāzima after him. This sample is not meant as an example but rather to show how the qerradeh is sung on stage or upon a specific occasion …

(♩)

Let us now go to the muwashshaḥ (plurimetric and plurirhyme Arabic poem) baladī. This other type of mountain rhythmic singing performed in the Lebanese mountains is also influenced by the Syriac tradition and close to the qerradeh. It is based on the number of syllables and does not respect the long and the short vowels like classical poetry. For example: “Dār el-dūrī ‘a-l-dāyir yā sitt el-dār” 7 /4; “Ḥāmil ha-l-oṣṣa w-dāyir dāyir mindār” 7 / 4. I recited them similarly. The score of this melody is full of eighth notes (“dhāt al-sunn” in Arabic). Even the musical score of a qerradeh that is full of eighth notes from beginning to end, where each syllable has an eighth note, and where there is no black note with an eighth note, illustrates the syllables’ equal duration that facilitates the poem’s structure and its collective rather than solo performance.

The beat in the end is for the breath, isn’t it?

Right. This is a very important point: the measure of the qerradeh poem is 7 /7, yet it is 8 /8 for the qerradeh song, and the measure of the muwashshah baladī poem is 7 / 4, yet it is 8 /5 for the muwashshah baladī song. The added beat is for the breath and the rhythm: there is an eighth note that allows both to breathe and to resume with the following hemistich.

In Lebanon, the muwashshah baladī is called as such for the following reasons: zajal singers call it ghazal because it is simple and beautiful and its poetry structure and singing are compatible with ghazal (love poetry). The appellation muwashshaḥ baladī differentiates it from the muwashshaḥ andalusī that is a major type of music in the Arab World and that originated in Andalusia. As for the muwashshaḥ baladī, some theories state that it did not originate in Andalusia but was still given the appellation muwashshaḥ because it is ornamented; yet its poetic structure and its performance are clearly Syriac.

Let us now go back to the psalm “L-Maryam yōldat Alōhō” that illustrates very well the 7 / 4 / 7 / 4 poem structure and whose melody is close to that of the muwashshaḥ baladī. I will sing both to illustrate this (♩).

“L-Maryam yōldat Alōhō” to the sikāh huzām includes an ascension to the A Flat. Instead of it being to the hijāz i.e. A Flat B Natural, it is to the A Flat B Flat, such as (♩).

It is a bayyātī aspect…

Exactly. And it is not used in Lebanon as often as in Syriac music.

In the muwashshaḥ baladī “Dār el-dūrī ‘a-l-dāyir yā sitt el-dār”, even if the poet does not know music, when ascending to the A Flat, he ascends to the B Flat and not to the B Natural.

It is a bayyātī aspect / nawā.

Yes.

This was concerning the muwashshah baladī.

I have samples:

Here is “L-Maryam yōldat Alōhō” recorded at the Holy Spirit University by a jawqa (ensemble of singers) …

(♩)

There is also a muwashshaḥ baladī performed by Zaghlūl al-Dāmūr and by a poet of the Mughrabī family who was a member in his band.

Note that the muwashshaḥ baladī is among the most beautiful music and poetry types in Lebanese zajal performed in duels, because it is short and allows the participation of the band, the people present, the raddīda…

(♩)

Dear listeners,

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

We thank Father Dr. Badih al-Hajj and we will meet again in a new episode.

“Durūb al-Nagham”.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)