Written by Sheikh Muḥammad al-Darwīsh

Composed by Muḥammad Afandī ‘Uthmān to the nahawand maqām, a sub-maqām of the ‘ushshāq maqām.

madhhab:

Kādnī el-hawa we sabaḥti ‘alīl Mitl el-nasīm fī rawd el-uns, ḥibbī amar

Tali‘ ‘ala ghuṣn, kulluh adab We ṭarab we gamīl, mā lūsh mathīl

dawr:

Li-el-ḥusni dah bi-el-ṭab‘i amīl Yallī tilūm dah shē’ bi-el-‘a’l, we-undhur kidā

The two recordings we will listen to throughout this episode were made by Gramophone.

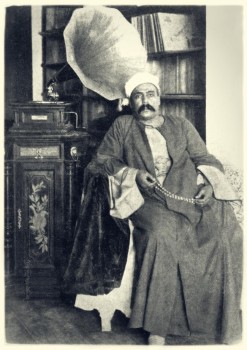

The first recording is by Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī, made around 1907, on three 30cm record sides, order # 012192 / 012193 / 012194, matrix # 1121 C / 1122 C / 1123 C.

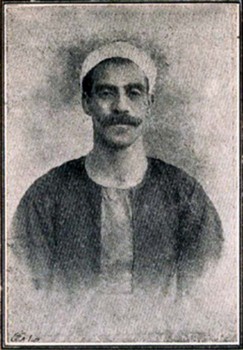

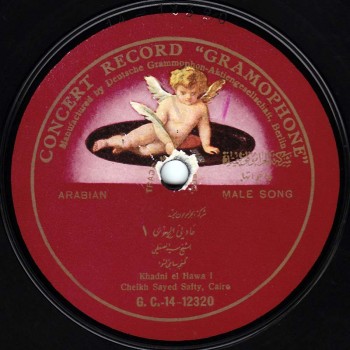

The second is by Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī, but recorded this time on three 25cm record sides. The duration of this record is then over 3 minutes shorter than the previous record’s duration. It was recorded around 1910, order # G.C.-14-12320 / G.C.-14-12321 / G.C.-14-12322, matrix # 1311 Y / 1312 Y / 1313 Y.

Approximately thirty years later, this dawr was recorded by Sāmī al-Shawwā who had played the kamān (violin) in the above-mentioned recording. He replaced the violin instrumental performance with a vocal performance in the recording made by “His Master’s Voice”, order # S.A.23, matrix # OAC 96-1 and OAC 97-1.

Let us now begin the analysis.

Dawr “Kādnī el-hawa” is among the famous adwār. Its success outlived the period it was composed in, reaching the second quarter of the 20th century, mainly because it is easy to play on the piano. Because, in their opinion, it was free of quartertones. Let us disregard this assumption now and go back to the dawr as it was composed. When composing this dawr, Muḥammad ‘Uthmān was certainly neither considering the piano as an option nor envisioning whether his piece would be played on the piano or not. To my opinion, the thought never even crossed his mind.

Dawr “Kādnī el-hawa” seems to be one of the last adwār composed by Muḥammad ‘Uthmān, since it abides by the concept of the set pattern that had not yet appeared at the beginning of ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī and Muḥammad ‘Uthmān’s school. It only appeared later. The set pattern consists of a pre-composed set madhhab followed by a dawr allowing improvisation to a great extent. However, this dawr must follow a set pattern, such as the repetition of part of the madhhab at the beginning of the dawr introducing the beginning of the tafrīd, followed by the āhāt or the layālī. The concept of the set pattern in this case is not thought to be the same as the concept developed by Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī and Dāwūd Ḥosnī, because the various recordings of this dawr show some respect of the set pattern. Yet, this is not a rule. For example, Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī would follow a certain pattern that Sheikh Sayyid al-Ṣaftī would not comply with, and vice versa. Let us conduct a step-by-step analysis of this dawr. The madhhab in the two recordings we have is almost the same. But the individual interpretations of each phrase’s melody are different. Anyway, this can never be standardized. Let us now discuss the dawr. Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī’s performance of this dawr –whose recording was made on three sides of a large size record– gives way to a lot of improvisation, while Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s recording –also made on three sides but this time of a smaller size record– allows less improvisation.

Let us study the first remark: Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī’s performance of the dawr is playful, cheerful and happy. It is not serious. Note that this record is the very first one Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī recorded with Gramophone. He had already recorded with “Sama‘ al-Mulūk” two years earlier, but this record is the first one made by Gramophone that reached us. Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s performance of the dawr is somewhat serious. Let us listen to the two singers’ versions of “Li-el-ḥusni dah bi-el-ṭab‘i amīl”. Sheikh Yūsuf’s performance includes a hābiṭa (descending phrase: the singing of successive notes, or sliding zaḥlaqa). This phrase is sung in a quasi-similar manner by Sayyid al-Ṣaftī. But comparing both performances shows the difference between Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s seriousness and Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī’s buoyancy and playfulness.

The difference in the performance as well as the difference in the way both these singers deal with this form are clear from the beginning. Let us now discuss the second remark concerning Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī’s performance of the āhāt phrase. Let us listen to it.

He is singing this āhāt phrase. So, it seems that it is part of the set pattern of the dawr. Sayyid al-Ṣaftī did not perform this phrase at all even though he, in the previous section –the shift to the rāst–….. . Let us listen to this shift performed by Sayyid al- Ṣaftī.

We note that Sayyid al-Ṣaftī extends the passage of the shift to the rāst while Sheikh Yūsuf’s performance of this same passage is brief. This constitutes yet another difference as to the set pattern. Note, again, the obvious major difference between both instrumental performances. Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī is accompanied instrumentally by Ibrāhīm Sahlūn, Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād and ‘Alī Ṣāliḥ. This implies a harmony made possible by their experience in working together since they had been accompanying him for a long time. Whereas the takht performing with Sayyid al-Ṣaftī accompanied him for recording purposes only. I do not think they accompanied him in his live performances. Let us listen to an instrumental interpretation phrase accompanying Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī, then to an instrumental interpretation phrase accompanying Sayyid Al-Ṣaftī.

Let us now study the layālī in the dawr. Note the masterful and parading performance of Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī. Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s performance is rigid, but the seriousness in the way he deals with the piece does not mean that his interpretation is a set performance. Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s performance is different from Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī’s playful performance. Let us listen to a short “Yā lēl yā ‘ēn” passage sung in the dawr by Sheikh Yūsuf and by Sayyid al-Ṣaftī.

As for the conclusion, they both perform it in a quasi-similar manner. When listening to the individual recordings, we can point out the difference between both singers’ performances. Now, I would like to go back to the rāst phrase and have you listen to a specific recording we will discuss but not listen to in full: it is the dawr recorded by Sāmī Afandī al-Shawwā at least 25 years after Sayyid al-Ṣaftī’s recording of the same dawr. Let us listen to the rāst phrase and note how Sāmī al-Shawwā’s performance sounds more like singing than playing the violin. This is a lesson all music professionals should follow: as much technical skill as one may master, one must learn how to sing because our music is originally based on the language meter. Even playing lyrics-free instrumental taqāsīm resembles the rhythm of the Arabic language. Let us listen to the rāst phrase “Li-el-ḥusni dah bi-el-ṭab‘i amīl” sung by Sāmī al-Shawwā.

Let us now listen to dawr “Kādnī el-hawa” composed by Muḥammad ‘Uthmān, or more specifically to the madhhab composed by Muḥammad ‘Uthmān. The first recording we will listen to is by Sheikh Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī. It starts with taqāsīm on the violin played by Ibrāhīm Sahlūn, followed by some layālī to the ‘ushshāq or the nahawand maqām –both designations can be used–, then by the dawr. We will listen to the dawr’s instrumental accompaniment with Ibrāhīm Sahlūn (kamān) –as mentioned earlier–, Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād (qānūn) and ‘Alī Ṣāliḥ (nāy).

We will now listen to Sayyid al-Ṣaftī singing the dawr. It starts with a nahawand maqām dūlāb. Then, Sayyid al-Ṣaftī sings the dawr, followed by some taqāsīm on the violin played by Sāmī al-Shawwā. The members of the accompanying takht are Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī (‘ūd), Maqṣūd Kalkajian (qānūn) and Sāmī al-Shawwā (kamān).

This is beautiful!

We end today’s episode of “Sama‘ “ with this great tune.

We will meet again in a new episode.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)