Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Min al-tārīkh”.

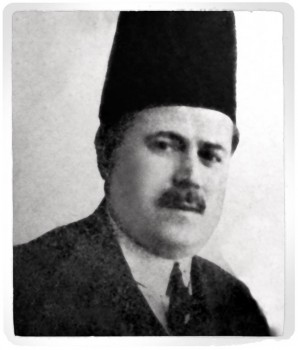

Today’s episode is about Zakī Afandī Murād.

Professor Frédéric Lagrange tells us about Zakī Murād:

F.L.: Zakī Murād can be approached from different angles.

Let us start with the religious one:

Zakī Murād was born to a Jewish family allegedly from Morocco around year 1880, and he died in 1946. Thus, he symbolizes the synergism achieved between the Muslims, Christians and Jews in 19th century Egypt for the sake of creating music…

It is also possible to approach Zakī Murād through his adherence to the contemporary generation of muṭribīn who did not go through the taḥzīm (granting of the belt – aptitude test).

Moreover, Zakī Murād is a very good representative of a generation who resisted the evolution that affected Arabic music, notably Egyptian music, at the turn of the early 1930s. He stopped singing then for good, probably in order to dedicate himself to training his daughter Layla Murād and his son Munīr Murād.

Now, concerning Zakī Murād’s biography:

His family had no history in music and he seems to have started off as a textile trader in Alexandria. Yet, he distinguished himself by his penchant for singing and ṭarab and, according to some sources, joined the musical club founded by Sāmī al-Shawwā in 1907. I personally have serious doubts about this particular issue. First, because Sāmī al-Shawwā –who was 15 at that time– could not have founded an establishment equivalent to a conservatoire in 1907. Secondly, because Zakī Murād who was born in 1880 –and thus was approximately 5 years older than Sāmī al-Shawwā– would not have accepted to be trained by young Murād, as talented as the latter may have been.

On the other hand, the scarce sources of information on Zakī Murād all affirm that there was a strong friendship between him and ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī, and that Ḥilmī is the one who trained and mentored him in singing. In fact, Zakī Murād’s first recordings bear the mark of ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī’s influence. Let us take for example qaṣīda “Arāka ‘aṣiyy al-dam‘” that clearly depicts Zakī Murād’s quasi imitation of ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī’s performance and style –knowing that ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī was himself influenced by ‘Abduh al-Ḥāmūlī.

Let us listen to Zakī Murād singing the beginning of qaṣīda “Arāka ‘aṣiyy al-dam‘”.

F.L.: With pleasure!

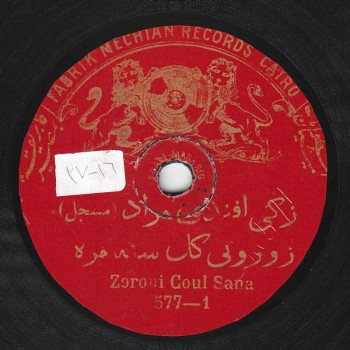

F.L.: Zakī Murād recorded numerous albums with Gramophone starting 1910. His relationship with producer Ibrāhīm Rūsho –Zakī Murād married Rūsho’s daughter Gamīla– helped his career and prompted his success.

The production of Zakī Murād is in fact dual:

On one hand, we have substantial information about him as a takht muṭrib since he recorded with almost all the period’s record companies –Al-Sayyid al-Ṣaftī and ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī had done the same, not giving exclusivity to any one of these record companies.

On the other hand, we almost know nothing about Zakī Murād the successful actor, because none of the roles he played in operettas in the early 1900s were recorded. Yet, we do know that he replaced Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī in some of his roles after the latter was stricken with hemiplegia in 1909. Murād also co-starred with Munīra al-Mahdiyya in the play “Cleopatra”, replacing Muḥammad ‘Abd al-Wahāb. The other successful roles he played include the role of Sayfiddīn in Badī‘ Khayrī’s and Sayyid Darwīsh’s play “El-‘ashra el-ṭayyiba”.

The question remains: why do we know nothing about Zakī Murād the actor despite the great success of the plays he participated in?

The plays are known, yet we know nothing of his performance in them, what songs he sang, how he used to sing them, or his style in performing operetta tunes. There are no recordings to attest to his participation except for very few made during WW1, some ṭaqāṭīq, and operetta tunes recorded by Meshian. Apart from those with Gramophone, Odeon and all the other record companies, his recordings are mostly of adwār, qaṣā’id and mawāwīl. After WW1, Zakī Murād seems to have followed the footsteps of ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī as one of the first male singers who performed ṭaqāṭīq, a genre exclusively reserved to female singers in the 19th century. The ṭaqṭūqa was entered into the male singers’ répertoire starting with ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī. As for Zakī Murād, he was one of those who performed ṭaqāṭīq as a man, unlike ‘Abd al-Laṭīf al-Bannā for example who sang them as a woman, at times giving an effeminate yet pleasant, well-liked and funny performance.

Zakī Murād participated in Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī’s commemoration concert, singing many of the latter’s musical pieces. There is a marvellous recording of Murād imitating Sheikh Salāma Ḥigāzī in his performance of “Yā ghazālan ṣāda qalbī.

Let us listen to “Yā ghazālan ṣāda qalbī” recorded by Zakī Murād with Baidaphon –while Salāma Ḥigāzī had recorded it with Odeon.

F.L.: Exactly.

F.L.: Why does this young man symbolize the changes that affected the music industry at the beginning of the 20th century?

I have already stated that he did not go through the taḥzīm test because he was a muṭrib under the tutelage of another muṭrib: ‘Abd al-Ḥayy Ḥilmī, and also because he had been chosen by the record companies. There is no doubt that this talented young man, a very talented singer indeed, appealed to the record companies’ producers who decided he was worthy of performing adwār. Let us not forget that the period’s record companies had taken the role of religious sheikhs and that the composers were those who were asked which singer would record a certain dawr. Upon the composer’s choice, the record company would sign a contract with the artist. Sometimes, the record companies commissioned a particular fannān (artist) to perform a certain piece.

In fact, there is a pleasant story told by ‘Abd al-Salām Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī –son of the famous composer Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī– in his book on his father. In this book, he mentioned Zakī Murād’s imitation of his father’s style in singing, saying:

“There is a pleasant anecdote that ought to be mentioned in this context: one of the period’s great singers, Zakī Murād, was chosen to record dawr “El-ṣulḥi bēnī we-bēn malīkī” composed by Al-Qabbānī.

Actually, we are going to listen to a short excerpt of this dawr recorded by Sayyid al-Ṣaftī.

Let us do that.

F.L.: So, the dawr was “El-ṣulḥi bēnī we-bēn malīkī”, and it seems that Zakī Murād considered it to be more modernist than was necessary. Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī’s son continues: “When the aforementioned muṭrib listened to the tune and was surprised by a new style characterized by vocal ranges, he asked to be excused from performing the dawr saying: “Why! Are we going to sing in the takht with western hats?” indicating that Zakī Murād was not used to this style in composing, and judged it as unfamiliar and foreign to Arabic music. But Al-Qabbānī answered him, saying: “You will witness much more than this in the future”.

Indeed, we did witness much more than that… in fact much much more than what Al-Qabbānī expected.

Of course, but let us take a moment to analyse this. It seems that Zakī Murād was relatively attached to heritage music and did not judge imported elements as being the prompters of evolution. Right?

F.L.: Of course.

While Al-Qabbānī was convinced that he was not creating much more than others, saying: “What I am doing is not worthy of being compared to what others are doing, or will do in the future.

F.L.: Exactly, but this story is a little strange. We would have believed it had Zakī Murād not participated in the operettas where foreign influence was much greater than it was in takht music. Maybe what we must conclude or understand from this story is that Zakī Murād drew a clear line between music evolution in the operettas where he accepted foreign influence, and takht music in which he resisted it. That is why he did not say “we will not sing wearing western hats”, but rather “we will not sing with the takht wearing western hats”, indicating that he probably saw what Al-Qabbānī was attempting to do and what Sayyid Darwīsh was attempting much further than Al-Qabbānī in his adwār, i.e., that this kind of evolution was not compatible with takht music which he was very conservative about.

Yet, even the style to which Zakī Murād sang his recorded ṭaqāṭīq and operetta tunes while accompanied by the takht was different from the style followed by other performers. If we take a look at the band accompanying other singers than Zakī Murād in operetta tunes, we will find western -not oriental- piano, flute, and violin. Whereas the takht accompanying Zakī Murād in the same operetta tunes others recorded complied with the takht‘s playing style that abided by the same music structure, including improvisation …etc.

F.L.: Your remark is true, yet we are not sure that the type of recording or the instruments accompanying the muṭrib recording operetta tunes were the same instruments accompanying him when he performed these same pieces on stage.

And we will never know for sure.

F.L.: Obviously.

Then let us listen to an operetta tune recorded by Zakī Murād.

F.L.: Let us do that.

F.L.: If we decide to tackle Zakī Murād’s genius, then we must listen to him performing adwār. I chose for our audience two adwār showcasing his talent extraordinarily. To my opinion, he surpassed our Mullah Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī’s performance of dawr “Fī zamān el-waṣl”. What is the particularity of dawr “Fī zamān el-waṣl” ‘s rhythmic mode?

The aqṣāk 9-beat rythmic mode, whereas a dawr usually abides by a 2-beat or a 4-beat rhythmic mode. The maḏhab is then a maṣmudī maḏhab followed by ‘alá al-waḥda ..etc. This particular dawr is different from others in this respect. We only have one example of a dawr to the aqṣāk rythmic mode: dawr “Fī zamān el-waṣl”, and one example of a dawr to the dārij 3-beat rhythmic mode: “El-ḥelū lammā n‘aṭaf”. Indeed, Zakī Murād’s choice of the aqṣāk mode is strange, and I too believe his performance surpasses Yūsuf al-Manyalāwī’s.

F.L.: Shall we listen to it?

Let us listen to it!

F.L.: This is so incredibly beautiful!

This dawr is by Sheikh ‘Abd al-Raḥīm al-Maslūb whose daughter married Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī.

We end this episode of “Min al-tārīkh” with these great tunes.

We will resume our discussion about Zakī Murād in our next episode of “Min al-tārīkh” during which we will listen to the aforementioned second dawr as well as to other works.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)