The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Sama‘ ”.

“Sama‘ ” is a show that discusses our musical heritage through comparison and analysis…

A concept by Mustafa Said.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Sama‘ ”

This is the first time our show discusses an instrumental work.

It is not true that instrumental music did not play a role in Arab music, and that the latter was limited to vocal works. According to all our sources, a significant part of the maqāmwaṣla was instrumental: an instrumental section introduced the waṣla, there were taqsīm before the mawwāl, and it also seems that an instrumental work was sometimes played before the dawr or before the qaṣīda. Moreover, according to some muḥaddith, purely instrumental waṣla were sometimes played in soirées.

The recording industry (recordings, record companies) in the early 20th century was an important source of income to musicians and to the record companies who recorded a significant proportion of instrumental works –not a small proportion, i.e. only one purely instrumental recording for each hundred records–. In some catalogues/booklets, instrumental works reached 20% or more of the listed works.

Along with famous singers, there were also famous instrumentalists: several records carry the mention “with Ibrāhīm Sahlūn’s takht”, “with Muḥammad Afandī al-‘Aqqād’s takht”, or “with Sāmī al-Shawwā’s takht”. Actually, the latter was so famous that the discs sometimes only mentioned “with Sāmī Afandī al-Shawwā’s violin”. There is even a disc of Kuran of “the ṣūrah of Yūsuf” mentioning “with Sāmī al-Shawwā’s violin” which implies that they probably resorted to this commercial trick as a proof of the high quality of the concerned disc.

Today we will discuss a “samā‘ī thaqīl bayyātī” whose composer is unknown.

This work is to the samā‘ī thaqīl 10-pulse’ rhythm (3 / 2 / 2 / 3)

The first 3: “dum iss iss”;

The first 2: “tak iss”;

The second 2: “dum iss”;

The second 3: “tak iss iss”.

Some place “dum” in the second 2, producing:

The first 3: “dum iss iss”;

The first 2: “tak iss”;

The second 2: “dum dum”;

The second 3: “tak iss iss”.

Thus:

“dum iss iss tak iss dum iss tak iss iss” and “dum iss iss tak iss dum iss tak iss iss” (1/2/3; 1/2; 1/2; 1/2/3 and 1/2/3; 1/2; 1/2; 1/2/3), i.e. the 10 pulses of the rhythmic measure.

This is the samā‘ī thaqīl rhythm of the samā‘īform that started, as mentioned in the episode about the samā‘ī,as a vocal form, then also became an instrumental form along with the vocal form. It is found in Turkey seemingly within the mawlawī style and later in mundane music: a very ordinary form that was not limited to Sufi music.

The samā‘ī thaqīl bayyātī seems to be an Arabic work, not a Turkish work.

In general, most instrumental works were composed in the Turkish court, by Turkish or non-Turkish musicians, and only later, it seems, in Arab courts. Yet no pre-18th century Arab works have reached us. Or maybe Arab musicians presented their works at the Ottoman court since it was the only court in the region that was interested in music and encouraged it. Consequently, all the musicians in the Sultanate went to the Sultan to present their works.

The samā‘ī bayyātī is opposed to the Turkish style: in the 4th khāna for example, the rhythm must change, either to the sankīn samā‘ī, the dārij, the yūruk, or any 3-pulse’ rhythm.

In our samā‘ī today, the rhythm stays the same: 1st khāna, taslīm, lāzima, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th khāna, are all to the same samā‘ī thaqīl rhythm.

It seems to have been composed in the 19th century, probably in the second half of the 19th century. While other sources date it back to the 18th century, which we can neither confirm nor deny.

The point is, when we analyse muwashshaḥ “Malā al-kāsāt” –a very evolved type of muwashshaḥ– without the improvised section, we end up with a form equivalent to the samā‘ī thaqīl bayyātī.

Let us listen to it before discussing it.

We have several recordings today:

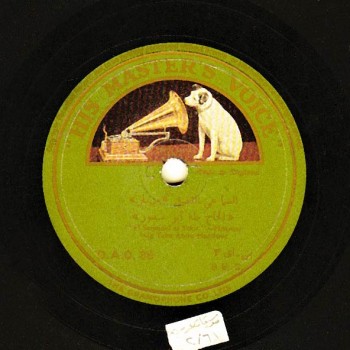

A recording of Sāmī al-Shawwā made in the early 1920’s by Gramophone;

A recording of Sāmī al-Shawwā made by Baidaphon;

A recording of Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn’s takht also made by Baidaphon;

A recording of Sāmī al-Shawwā made by Polyphon;

The last recording we will listen to at the end of the episode is a surprise: it is a recording of Ḥāj Ṭāh Abū Mandūr’s mizmār band.

Let us listen to Baidaphon’s recording of Sāmī al-Shawwā with Zakī al-qānūnjī, Petro al-‘awwād, and Sheikh ‘Alī al-Darwīsh (nāy), made around 1924 in Beirut. We will dissect it afterwards…

(♩)

Wow!

In this recording, the performance of the full takht –‘ūd, qānūn, kamān, and nāy– is pleasantly lively.

The performance of Sāmī al-Shawwā of this same work may be a little different in another recording.

Let us start our analysis.

As described earlier, the samā‘ī’s pattern is as follows: 1st khāna / lāzima / 2nd khāna / lāzima / 3rd khāna / lāzima / 4th khāna / lāzima.

The lāzima is one same melody repeated between the khāna.

Some samā‘īinclude a taslīm that relays from the khāna to the lāzima.

This samā‘ī includes a taslīm and a lāzima. Its pattern is as follows: khāna / taslīm / lāzima / khāna / taslīm / lāzima… etc.

The taslīm and the lāzima consist in the same repeated melody.

The 1st khāna is to the jahārkāh maqām and consists in one rhythmic measure only. Let us listen to it…

(♩)

The same melody is repeated twice in order for the 1st khāna to last as long as the following khāna.

So it consists in one rhythmic measure, one same melody performed twice. (♩)

(♩)

It is followed by the taslīm that relays from the khāna’s maqām to the initial bayyātī maqām of the lāzima.

Consequently, the bayyātī sets on the nawa then ends at the dūkāh, i.e. the second main note after the initial position is the nawa.

It is as follows:

(♩) 1st measure

then

2nd measure (♩)

He is implying that the bayyātī’s position is the note of the initial position and that the main note is its 4th note, i.e. the nawa.

So he plays the nawa then sets on the dūkāh.

Let us listen to the taslīm…

(♩)

The lāzima should consist in 3 rhythmic measures. But the first one and a half rhythmic measure, i.e. 15 pulses, constitute a new melody, while the following 15 pulses constitute the second half of the taslīm’s 1st measure and the rest of the taslīm. So 3 quarters of the taslīm are included in the lāzima.

The lāzima(♩) stops at the rāst not at the dūkāh.

Then he relays to the nawa that is a part of the taslīm, as mentioned previously (♩).

Then he concludes to the dūkāh (♩), the same conclusion to the dūkāh as the taslīm.

Let us listen to the lāzima of this samā‘ī…

(♩)

This was to the bayyātī maqām. We now know without any doubt that the samā‘īis to the bayyātī maqām.

In the 2nd khāna, he goes to the rāst from the 4th scale-step, i.e. the rāst nawa.

He performs the nawrūz, a rāst sub-maqām, i.e. a muḥayyar: a rāst initially and a bayyātī sub-maqām.

This is heard in most recordings, as if agreed upon subconsciously.

Let us listen to the 2nd khāna to the rāst that consists in 2 rhythmic measures…

(♩)

Let us listen to the same khāna and to the taslīm that takes us back to the lāzima, and then to the lāzima: the 2nd khāna and its route to the taslīm through 2 measures, and to the lāzima through 3 measures. So we will hear 7 rhythmic measures: the 2nd khāna, the taslīm, and the lāzima separating the different khāna…

(♩)

The 3rd khāna is to the ḥijāz maqām. Which implies that he changed the scale order that was until now the sulṭānī scale order including the sīkāh and the awj (according to the very old description: yakāh dūkāh sīkāh jahārkāh banshkāh shīshkāh haftkāh and their jawāb. Many call it the sulṭānī tuning). So he changed the tuning and altered the jahārkāh scale-step and replaced it with the ḥijāz scale-step. So he went up by a minor semitone from the jahārkāh to the ḥijāz.

The 3rd khāna is the first alteration of the sulṭānī scale order, and it also consists in 2 rhythmic measures.

Let us listen to it…

(♩)

Note that the 2nd and the 3rd khāna have the same melody, the same rhythmic structure. Yet the melodic structure is responsible for this faṣl: both the 2nd and the 3rd khāna have the same tempo, i.e. the same interludes in the melody. The only difference is that one is to the rāst while the other is to the ḥijāz.

Let us listen to both khāna and notice…

(♩)

The melody is the same. Its nature only changes following the note.

Let us listen to the 3rd khāna followed by the taslīm, then the lāzima…

(♩)

In the 4th khāna, the nawa note was altered. He brought back the jahārkāh and replaced the ṣabā with the nawa. He also went down from the nawa by a minor semitone, as well as from the ṣabā to the ḥijāz by no more than 2 “comas”: the ḥijāz and the ṣabā are not exactly the same, the ṣabā is higher.

The ṣabā note is called “delārā” by some, as well as in Turkey where it is considered to produce an aspect of the ḥijāz from the jahārkāh. The point is that the 4th khāna is to the ṣabā and that the rhythmic structure is a little different from that of the 2nd and the 3rd khāna.

Let us listen to the 4th khāna separately…

(♩)

He played the ṣabā following the old way: he used the zarfākand note that is a minor semitone higher than the rāst, maybe even ¾ less than the dūkāh, not only a semitone, maybe more, a little less than a semitone higher than the rāst. He played it as a type of ornamentation that embellished the ṣabā.

I heard it as a young boy for the first time, and benefitted from it a lot later on.

Let us listen to the 4th khāna, this time with the taslīm and the lāzima following it…

(♩)

We do not know how this samā‘īwas performed in live concerts.

According to some, taqsīm were performed to the samā‘ī thaqīl rhythm, while according to others, they were performed to the bamb before it. Others say that they used to play it as is.

In some recordings, the 1st khāna, the taslīm, and the lāzima were repeated after the samā‘īin order to fill the remaining duration on the disc.

According to others, even the 1st and the 2nd khāna were repeated, as if starting again from the beginning.

Yet these repetitions were undoubtedly performed to fill the remaining duration on the disc.

I think that in live performances, it was played as is or was maybe preceded by taqsīm to the bamb or to any other rhythm, and followed by the muwashshaḥ or the rest of the waṣla, or maybe by taqsīm to the same samā‘īrhythm.

We have heard Baidaphon’s recording.

Let us now start our journey with Sāmī al-Shawwā, Ibrāhīm al-Qabbānī, and ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī. The recording was made towards the end of 1923 (I think) by Gramophone. We will listen to the full record because the samā‘ī is recorded on the second side, preceded by a taqsīm to the bamb and a istihlāl (overture) to the bayyātī maqām on the first side.

By the way, Sāmī al-Shawwā first recorded the samā‘ī then the taqsīm and the istihlāl. But the taqsīm was printed on the first side and the samā‘ī on the second side. Maybe this is a type of de-structuring of the waṣla, meant to imply that the latter had already started and that those sections were in the middle.

Sāmī al-Shawwā recorded it in this manner and decided to print it the other way around.

Let us listen to the samā‘īand notice the dialogue between the kamān alone and within the group during the samā‘ī.

Sāmī al-Shawwā sometimes stopped playing to allow the other instrumentalists to perform ornamentations. He knew that the sound of his violin –the only “pulling” instrument– would be more audible on the disc, so he gave them the opportunity to perform ornamentations. (He had been recording for 16 or 17 years and was fully aware of the result in the recording).

Let us listen to the whole disc and notice this dialogue amongst the instrumentalists.

(♩)

Four years later, Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn recorded a disc similar to Sāmī Afandī al-Shawwā’s, accompanied by a qānūnist and a ‘ūdist while he played the ṭanbūr baghdādī, i.e. the buzuq. Those accompanying him seem to be Zakī al-qānūnjī (qānūn), Petro al-‘awwād (‘ūd).

Let us listen to this recording and note how close it is conceptually to Sāmī al-Shawwā’s taqsīm. Also note his individual personality as a musician: he did not try to imitate, he liked the idea and decided to do something similar without imitating. He did not try to be himself Sāmī al-Shawwā playing the buzuq.

It is similar except that there is no istihlāl to the bayyātī at the end of the first side in Sāmī al-Shawwā’s recording.

Let us listen to this disc and note how Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn deals with the ‘ūd and the qānūn accompanying him and how, despite the presence of three percussion instruments in the takht –an improbable occurrence at the time– the performance is not chaotic.

Let us listen to Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn’s recording made around the end of 1927 by Baidaphon on an electrical-power printed record.

Note the concept of su’āl and jawāb between the ṭanbūr baghdādī, i.e. the buzuq, the ‘ūd, and the qānūn.

(♩)

Wow! Beautiful!

Let us go now to the recording on which we based our explanation of the samā‘ī: it is the recording of Sāmī al-Shawwā (kamān), Shaḥāta Sa‘āda (‘ūd), and ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī (qānūn) made by Polyphon on an electrical-power printed record around two years after Muḥyiddīn Ba‘yūn’s recording. We have already listened to Sāmī al-Shawwā’s very impish recording made by Gramophone. The same musical score is now played by him in a calm and composed manner in a performance displaying the different ways to interpret the phrase, not the different techniques…etc.

The recording was made on one side only because it is neither preceded by taqsīm nor by anything else. Moreover, the 1st khāna was repeated, certainly to fill the remaining duration on the disc.

Despite that the qānūn in the late 1920’s and 1930’s was mainly played with ‘urab, ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī and Muḥammad al-‘Aqqād play it here without ‘urab. It is as if ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī wanted to prove that this qānūn was as powerful as the other qānūn, and that it was the original indispensable one.

Now, apart from this controversy, ‘Abd al-Ḥamīd al-Quḍḍābī interprets the musical score on the qānūn with an extraordinary technique in this recording. Moreover, his structuring of the phrase seems to be born from decades of experience in dealing with instrumental musical scores.

As for Shaḥāta Sa‘āda, notice how he plays the samā‘ī with his famous pick, note his silences and how he sometimes breaks them with his pick, how his left hand plays notes that are different from those he plays with the pick…

It is a great 3 minute’ recording, a different interpretation and a different performance of this samā‘ī that can be interpreted in an indefinite number of ways.

(♩)

Last but not least, and relatively to the issue of the different interpretations of a musical score, let us listen to Ḥāj Ṭāh Abū Mandūr’s mizmār band playing this samā‘ī. Note how the musical score was interpreted on the mizmār, i.e. the zurnāy –an instrument that can only produce a very limited number of notes– and how they tricked their instrument into producing notes it could not initially produce. Here is the great Ḥāj Ṭāh Abū Mandūr’s mizmār (or zamr) band.

(♩)

Ṭāh Abū Mandūr recorded it during the conference and the recording was published some time before this recording.

Before the end of this episode, note that the concept of a musical score in classical Arab music is ever-changing and depends on the interpretation of this musical score. I do not imply a “Rock and Roll” interpretation of the samā‘īfor example… Even though it is a point of view… We did hear a folkloric interpretation performed by mizmār.

Each way to perform it is a point of view itself.

Anyway, the point is that a musical score performed by the takht’s ordinary instruments or maybe one instrument playing solo, may include elements that allow different interpretations, preventing any kind of monotony and thus avoiding boredom. The musical score is neither a fixed letter nor a set paper, it can be expressed following one’s interpretation.

(♩)

We have reached the end of today’s episode of “Sama‘ ”.

We will meet again in a new episode to discuss and analyse another work.

“Sama‘ ” was presented to you by AMAR.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)