The Arab Music Archiving and Research foundation (AMAR), in collaboration with the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF), presents “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Dear listeners,

Welcome to a new episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Today, we will resume our discussion about the ‘ūd with Mr. Mustafa Said.

Does the type of training depend on whether a musician decides to be a soloist or an accompanying instrumentalist?

To me, the concept of virtuoso or soloist is not important in our music and traditions. We are under an autocracy, yet people have made up for this repression through music that relies significantly on group performance. Note that the latter does not imply that the musicians and instrumentalists are a tool in the hand of the author whom they must obey as in a symphonic orchestra. The performance is intrinsically linked to the writing and composing, and the collective performance is consequently the soul of writing. Furthermore, even today and anywhere in the world, the concept of the solo virtuoso instrumentalist who is adulated and applauded by his audience and must sign autographs after his concerts is disappearing. Today, people want to listen to music. Such demonstrative performances were trendy during the industrial revolution. Today, people have gone beyond this. Even the concept of the child prodigy is almost extinct. So it is all a matter of personal opinion. Collective performances are pleasurable on all levels. Most soloists, like pop stars, are tense, nervous, and afraid before their concerts. They hope the audience will like them. Yet, one should perform to make himself and the audience happy… pleasing people while being tense and scared is not appealing to me. At the end of the day, it is a matter of opinion, one can’t say he is right and the other is wrong.

On the other hand, one should master solo taqsīm-s (modal improvisation) and improvisation within the group, in order to come out individually.

The instrumentalist playing in a group performance must master solo playing as the group includes only one of each instrument. He is thus a soloist performing within the group. So, he can interpret a bashraf (fixed and metrical cyclic composition consisting in an alternation of (two to) four different sequences –khānā– with a taslīm (bashraf and samā‘ī ritornello) ritornello, on sometimes extended generally binary percussive cycles) or any other work from his own perspective, as long as he knows when to pause and let another perform ornamentations. If he plays and ornaments non-stop, preventing another from participating, he would then be ruining both the solo and the group performance. Individual mastery that will allow for collective success resides in knowing when to play, when to pause, when to play solo, when to let another play, when to relay, and when to take over.

So, he is a soloist amidst a group!

Naturally …

(♩) (bashraf qarah baṭāq sikāh – Muḥammad al-Qaṣṣabgī, ‘Alī al-Rashīdī, Sāmī al-Shawwā. Columbia Records)

What distinguishes an instrumentalist from another?

His personality, lack of complex, self-confidence, cooperation, and most importantly his lack of individualism in dealing with the work. Even when one is to play solo, a lack of cooperation whether with the sound or the light technicians would cause the atmosphere to be tense. Whereas, whether you are playing solo or in a group, if you are cooperative, wholeheartedly agreeable, in full mastery of all your tools, and without any complex, then you will surely be unique.

How does an instrumentalist distinguish himself on the technical level?

In fact this concerns any musician, whether he is an instrumentalist, or a singer, or anything else.

First, he must be sure that music is what he wants and not just something to kill time, and that he has passion –sometimes called talent– for music… This will show with time.

If he feels like learning music, then this is another issue…

He must train a lot: those who claim that they do not train, and that their inspiration comes from above are talking nonsense. Training plays a major part in forming the personality, whether it is on the technical level –training technically with an instrument is important–, or training by playing and memorizing works, or listening.

Here are the steps in order of importance:

Listening is the most important as it counts for more than half the training. It does not mean listening while having dinner though. Listening means to do so in order to effectively hear and store.

Memorization;

Interpretation;

Technical Training: it is necessary and compulsory to train a lot;

Group Performance: one must work within a group as much as possible. Training alone cancels one of the necessary elements of training. Working together is a major and intrinsic element of the musical built.

The presence of others induces feedback and self-criticism that helps one to better himself.

So it leads to constructive criticism by others and through self-evaluation.

Yes.

Marvelous …

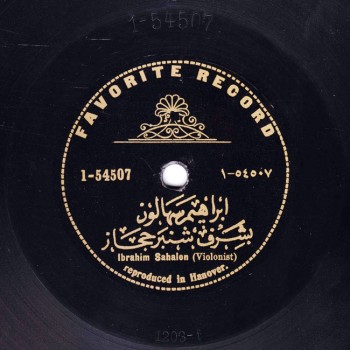

(♩) (shanbar ḥijāz – Ḥāj Sayyid al-Suwaysī, Ibrāhīm Sahlūn, ‘Abd al-‘Azīz al-Qabbānī. Favorite Records)

What do you think of the future of ‘ūd?

It is going down the drain…

No… Let us be fair. The situation today is better than it was 20 years ago. There is way more interest in non-electronic instruments than in the 1980s and 1990s when the situation of these instruments was bad. People have gone back to making ‘ūd-s, qānūn-s (trapezoidal table zither with 24-25 three-string’ courses. It is played with two plectra attached to the thumbs of both hands), violins, nāy-s (oblique reed flute) and percussion instruments from natural materials and not from plastic. This is all having a very positive impact today, which augurs well for an improved future. Things will be better when people get rid of their inferiority complex, of self-importance, etc. … The future of ‘ūd is linked to the future of Arab music / maqām (musical mode) music. I am noticing an improvement: the majority of listeners are evolving, especially after the spread of alternative media that, besides unveiling duds that had better stayed in the dark, has also shed light on pieces that were ignored by regular media simply because they do not generate money. This is a positive point, added to the fact that people have started to make a distinction… There is great hope for the future.

What about the evolution of the ‘ūd from the beginning of the recording era until today? Did it evolve on the following levels: techniques, sound, workmanship, and the played repertoire?

The repertoire has evolved significantly: at the beginning of the recording era, people played the existing repertoire of the mid 19th, the early 20th century, and some remaining 18th century pieces. Today, thanks to Cantemir, ‘Alī Ufqī Bēk, Quṭb al-Dīn al-Shirāzī, al-Marāghī, and Ṣafyiddīn al-Urmawī, we have a bigger and older repertoire. So, these discoveries have resulted in a new “old repertoire”. Furthermore, those who recorded at the beginning of the recording era and those who followed constituted a new repertoire. Learning about other cultures through recordings, expansion and spread through the Internet all led people to extend their abilities both intellectually and technically. Manufacturing was in dire straits for 10-15 years. People were listening to bells, to fast food sounds. Whereas, the last decade witnessed a significant evolution as to the manufacturing. Now people are listening again to the sound of a ‘ūd that is neither “boxed” nor “bell sounding” (from the word “bell”), and working hard, developing their playing based on old manuscripts and still-existing old ‘ūd-s, and reaching good results. Note that not everything that is old is necessarily good. Today, we are able to produce pleasant, good, evolved contemporary sounds. We have even discovered that the sound produced by the Stradivarius is not the best violin sound.

Do not produce bell sounds, sharp sounds, or boxed sounds, but do not either be a parrot or a machine that re-produces an existing tune. It is possible to create an independent work that still follows a rule.

Mr. Mustafa, can you play for us a selection of your instrumental works?

Alright …

(♩) (taqsīm rāst – Mustafa Said. Beirut, 2008)

Dear listeners, we have reached the end of today’s episode of “Durūb al-Nagham” about the ‘ūd presented with Mr Mustafa Said.

We will meet again in another episode of “Durūb al-Nagham”.

Today’s episode was presented by Fadil al-Turki.

“Durūb al-Nagham”.

- 221 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 12 (1/9/2022)

- 220 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 11 (1/9/2022)

- 219 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 10 (11/25/2021)

- 218 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 9 (10/26/2021)

- 217 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 8 (9/24/2021)

- 216 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 7 (9/4/2021)

- 215 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 6 (8/28/2021)

- 214 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 5 (8/6/2021)

- 213 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 4 (6/26/2021)

- 212 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 3 (5/27/2021)

- 211 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 2 (5/1/2021)

- 210 – Zakariyya Ahmed – 1 (4/28/2021)

- 209 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 2 (4/6/2017)

- 208 – W-al-Lāhi lā astaṭī‘u ṣaddak 1 (3/30/2017)

- 207 – Bashraf qarah baṭāq 7 (3/23/2017)